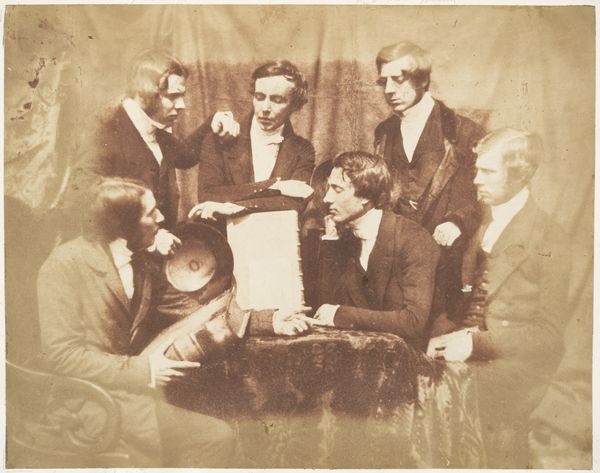

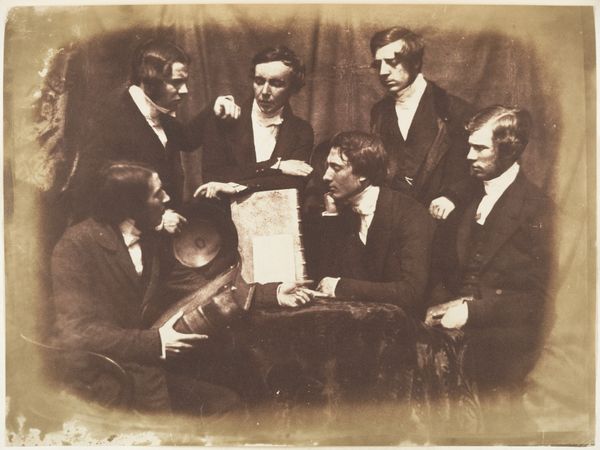

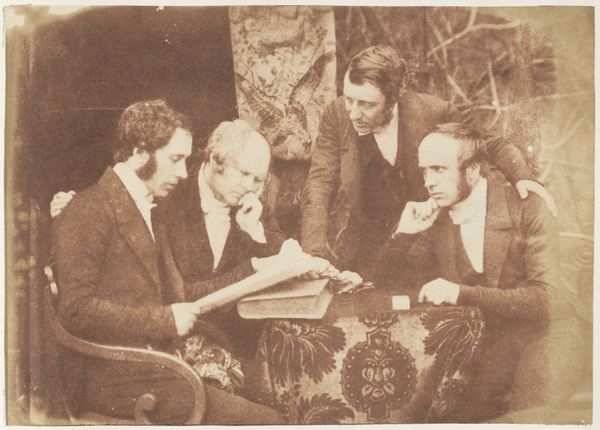

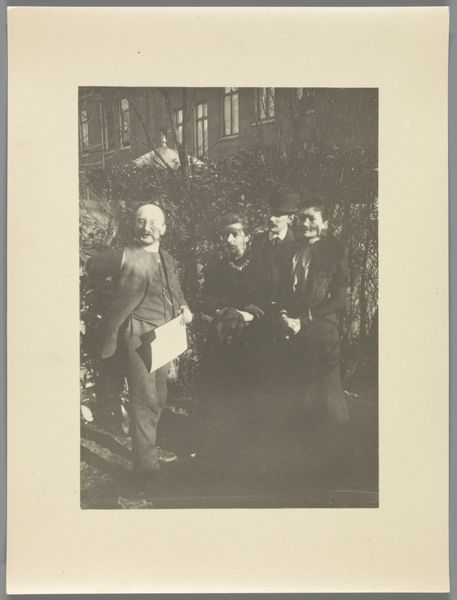

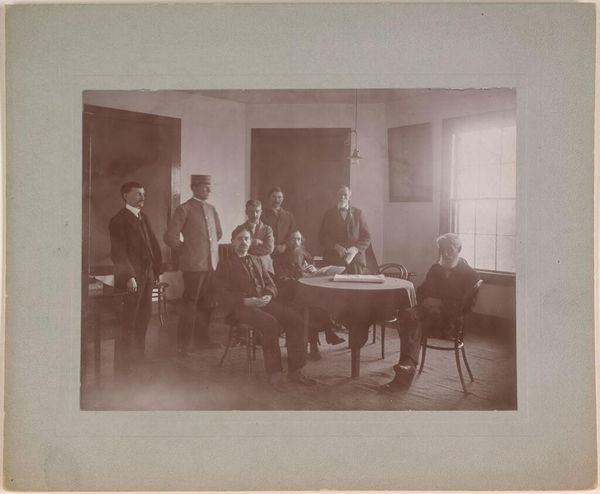

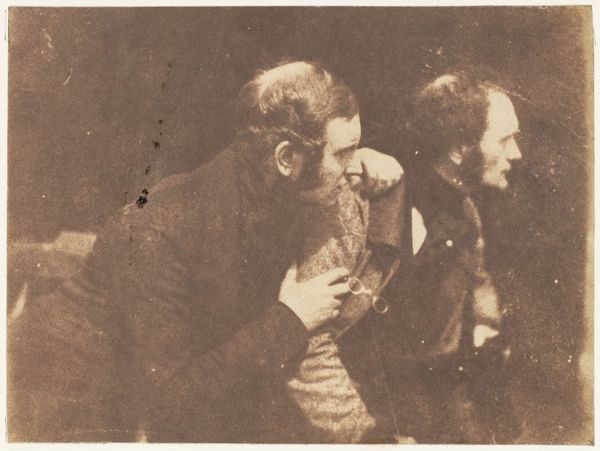

Cunningham, Beff, John Hamilton, Guthrie 1843 - 1847

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

group-portraits

#

19th century

#

men

#

genre-painting

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have a daguerreotype from 1843-47, "Cunningham, Beff, John Hamilton, Guthrie," by Hill and Adamson. The grouping of these figures seems so posed, stiff almost. It has an antiquated feel, of course, but also a kind of official quality, like we're looking at a board or committee. What historical narratives do you see at play here? Curator: Well, the very act of making a daguerreotype at this time speaks to socio-economic status and power. Who had access to this technology, and who had the leisure time to sit for these portraits? Group portraits, particularly, signal a certain kind of collective identity, a shared purpose perhaps within a specific social or professional sphere. Notice how they present themselves - their clothing, their postures - how might they have wanted to be perceived? Editor: I hadn’t really thought about it that way, as a visual performance. I suppose they are trying to project authority or… stability? Is this tied to the development of photography as a social practice? Curator: Precisely! Photography in the mid-19th century was deeply intertwined with burgeoning middle-class identity, scientific advancements, and the rise of public institutions. How did portraiture, historically a tool of the elite, democratize through this new medium, and perhaps even more critically, who remained excluded from this democratization? Did this representation in early photography reinforce power dynamics already in place, or did it disrupt them in some way? Editor: So, it's less about the specific identities of these men, and more about what they represent within the context of early photography and its role in society? Curator: It's about both, wouldn't you say? Considering both can provide a deeper understanding of the complex relationships between art, power, and representation in the 19th century. Editor: This really makes me rethink what a "simple" portrait could communicate. It’s much more nuanced than I first considered.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.