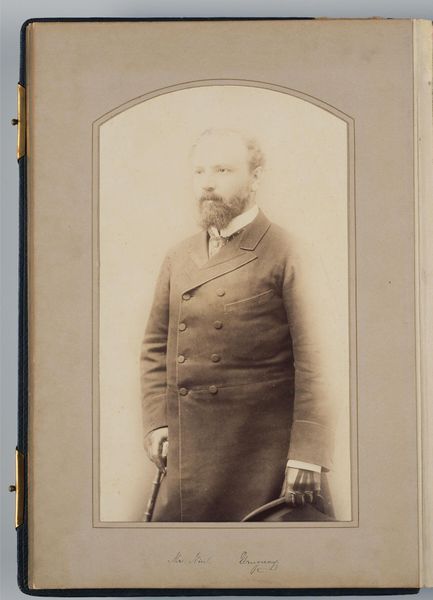

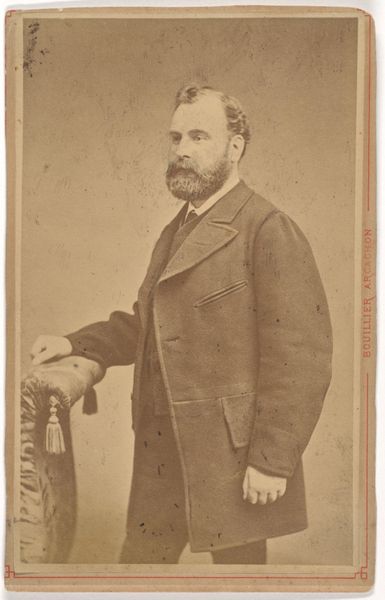

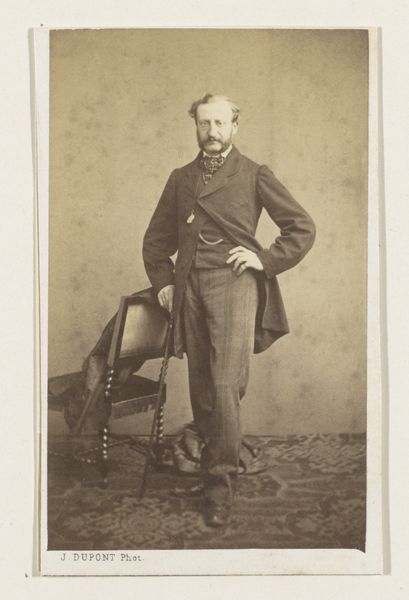

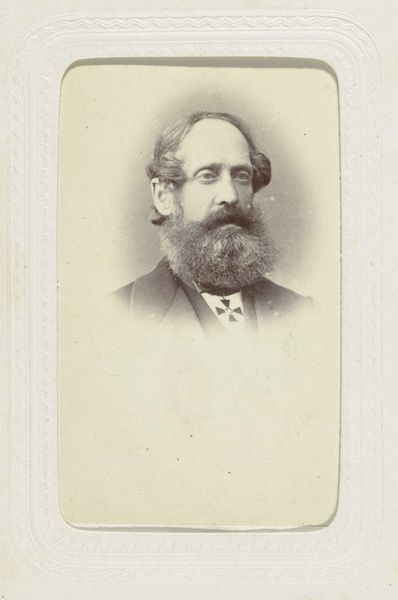

Studioportret van een man in kostuum met een wandelstok en handschoenen in zijn hand en een hoge hoed rustend op zijn arm c. 1863 - 1866

hermanngunter

Rijksmuseum

photography, albumen-print

portrait

photography

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 54 mm, height 296 mm, width 225 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's turn our attention to this studio portrait of a man, captured between 1863 and 1866, and currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. The photographer, Hermann Günther, rendered this gentleman in a very typical style for the period: with his walking stick and elegant hat, this albumen print represents an important part of portraiture in the mid-19th Century. Editor: There’s something undeniably formal about the portrait. I immediately notice his guarded stance, his hand concealing most of the walking stick. Even his impeccably maintained facial hair speaks volumes, like a symbolic barrier or a personal emblem he’s carefully cultivated. Curator: Precisely! The albumen print, a photographic process popular then, gave photographs a distinct sepia tone. It was an interesting time, as photography transitioned from a novelty to a tool used widely for record-keeping but also for self-promotion by the emerging bourgeoisie. Editor: And that tone does a lot of work for the period, doesn’t it? I wonder, beyond documenting status, what it suggests psychologically. It has the symbolic weight of bygone eras when photography was inextricably bound to portraiture as an extension of ancestral heritage. Curator: Indeed. The sitter's formal attire--a suit with distinct fabric details--mirrors societal expectations and the importance placed on outward appearances. These garments signal a level of cultural knowledge about fashion in that epoch, which in turn becomes a visual signal in the present. The costume in many ways constitutes a persona of the day. Editor: That persona, or "role" of citizen and man, then gets reinforced by his choice of accessories. The hat is obviously meant to indicate social position and the stick offers not only physical assistance but visual dominance. How much, I wonder, were such portraits also performative displays of national pride during times of intense geopolitical shift? Curator: Definitely, we see the solidification of class identity that characterized the second half of the 19th century as states gained their borders. Well, what a journey into 19th-century aesthetics, politics, and the art of the photographic portrait. Editor: I completely agree; It’s these layers of historical and personal meaning that make such images continue to speak to us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.