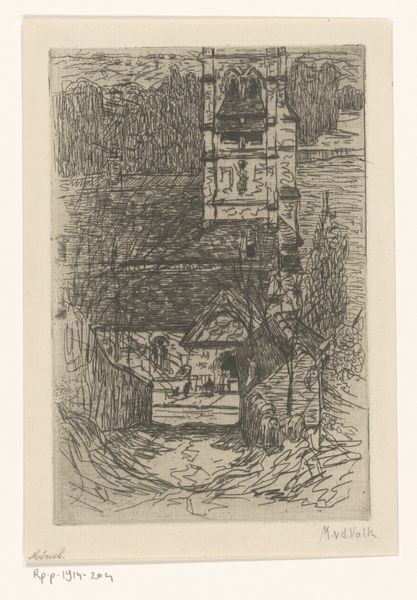

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

coloured pencil

#

romanticism

#

pencil

Dimensions: 192 mm (height) x 135 mm (width) (bladmaal)

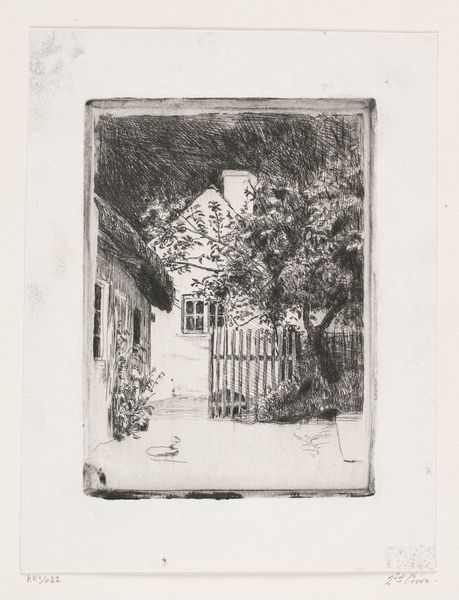

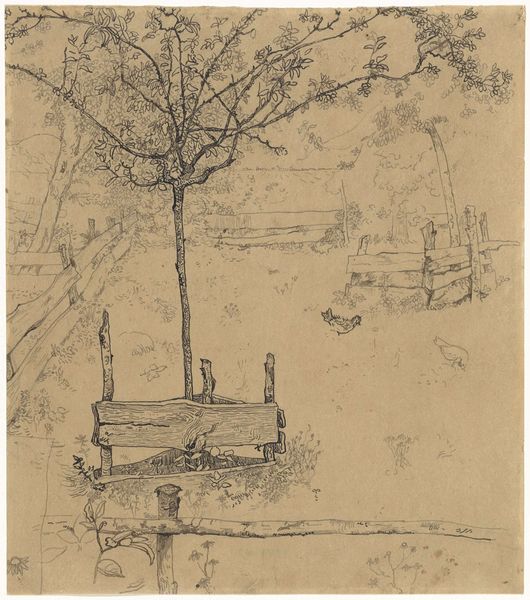

Curator: There's a certain hushed intimacy in Ernst Meyer’s drawing, "An Open Garden Gate Overshadowed by Vine Leaves." It’s from 1826, and rendered in pencil. What strikes you initially about it? Editor: It feels like a secret world. The shading is so delicate, but it creates these strong diagonal shadows that pull you towards the light beyond the gate, a suggestion of paradise perhaps, just out of reach. There's a clear dichotomy in play. Curator: Absolutely, the gate is such a loaded symbol. On one level, we see a boundary, but the vines draping over it soften the harsh lines. Throughout history, the gate has been symbolic of threshold, or entrance to knowledge, so here, one might consider themes of accessibility or inaccessibility that are at play in the composition. Editor: That's a beautiful observation. I'm struck by the almost claustrophobic effect of the vines versus the promise of openness hinted at. Does that speak to the period? What was Denmark like in 1826? Curator: Politically, it was a time of rebuilding after the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna, which might account for some of the visual tension present. Socially, Romanticism was in full swing. The focus on nature, emotion, and the individual is apparent. Editor: I see that so clearly here – it feels like a very private, personal moment captured in time. There are even handwritten notations in the lower right, indicating the kind of specificity that characterized that historical turn towards the empirical. Do we know why he made it? Curator: Meyer was primarily a genre painter, so this could have been a study. But considering the Romantic period's intense interest in nature, and given the careful detail of the foliage, I am struck by this small piece of observation. One can imagine, within the right-wing and patriarchal constraints of 19th century landscape art, the drawing may act as quiet, verdant space of contemplative introspection, both by the artist and by us as the viewers. Editor: That reading opens it up in a totally unexpected way. To me, it started out as just a charming landscape study, but it reveals itself to be so much more with careful thought about its composition, materiality, and history. Curator: Yes, there is a gentle radicalism at work, too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.