painting, oil-paint

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

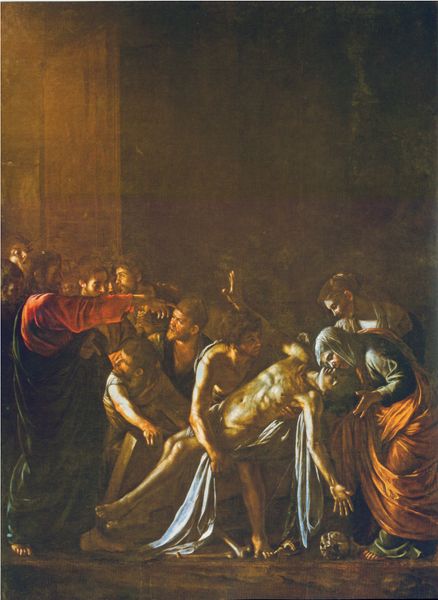

Dimensions: 207 cm (height) x 240 cm (width) (Netto), 234.5 cm (height) x 273.5 cm (width) x 11.5 cm (depth) (Brutto)

Curator: Standing before us is Hendrick ter Brugghen’s “Christ Crowned with Thorns,” an oil painting completed around 1620. It’s currently part of the collection here at the SMK. Editor: Immediately striking is the somber tonality and the density of figures crowding Christ. The deep reds and browns create an intense atmosphere. Curator: Brugghen was deeply influenced by Caravaggio's use of chiaroscuro, that strong contrast between light and dark, which is quite evident here. But consider also the social environment that would find the macabre appealing, almost decorative. Editor: The dramatic lighting certainly guides the eye, particularly highlighting Christ's bowed head and the glint of metal on the soldier’s armor. I'm drawn to the textural contrast as well, between the smoothness of the skin and the roughness of the garments. Curator: And how those garments indicate the varied trades present—the roughspun of the laborers and the shiny armour of the state enforcers. The materiality of the clothing acts as another signifier in this cruel narrative. It's a stark depiction of labor and power. Editor: It's a carefully constructed composition, though. Note how the lines of sight converge toward Christ, emphasizing his isolation even amidst the throng. There’s a real dynamism in the arrangement, enhanced by the artist's brushstrokes. Curator: Brugghen's time in Italy was also formative, of course. Look at how the religious content intersects with commercial interests – these works commissioned for wealthy patrons eager to display both their piety and their financial prowess. Editor: Well, I see it more as an exploration of form, line, and light that evokes a powerful emotional response from the viewer. The sheer physicality of suffering is palpable. Curator: Indeed. And recognizing that such palpable, physical forms become commodities within a very specific economic structure should further deepen our engagement. Editor: Ultimately, it’s Brugghen's mastery of technique that makes "Christ Crowned with Thorns" a compelling and enduring work. Curator: And seeing it not just as a static "masterpiece," but as a product shaped by social forces, expands our understanding of its creation and impact.

Comments

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

This scene, showing the crowning of Christ with thorns in the forecourt of Pilate's quarters, employs a triangular composition where the uppermost point is formed by the right hand of the soldier in the back. The soldier holds a rod that he has previously used to hit Christ. With this hand as the starting point, a tale told by hands can be traced all the way down through the middle of the painting. All the powerful, acting, gesticulating hands provide a contrast to the two hands of Christ himself: one has fallen down between his legs while the other rests on his right knee, tied up and limp. The language of hands plays out a true drama against the background of a fluted pillar that symbolises strength, in this case the strength of Christ.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

Christ is shown with his head down, quietly suffering in the forecourt of Pilate’s palace, surrounded by jeering soldiers. The scene depicts one of the torments that Christ was subjected to on the long Friday that ended in his death upon the Cross. Mockingly he has been called the King of the Jews, and now his tormentors have crowned him with thorns and wrapped him in a scarlet cloak to indicate his kingly stature. One of the soldiers kneels before Christ in mock humility, handing him a stick in lieu of a sceptre. The Utrecht Caravaggists Hendrick Ter Brugghen spent his formative years in Rome where the painter Caravaggio (1571-1610) became the main influence. Upon his return Ter Brugghen became the prime mover of a new school, the Utrecht Caravaggists, whose trademark style was an insistent naturalism combined with a high-contrast vein of painting known as clair obscur (light-dark). The North European tradition Even so, Ter Brugghen’s painting did not completely abandon North European tradition. The soldiers’ leering faces and the slightly angular body language has roots stretching back to late Gothic altarpieces and print series depicting the Passion, e.g. those by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528).