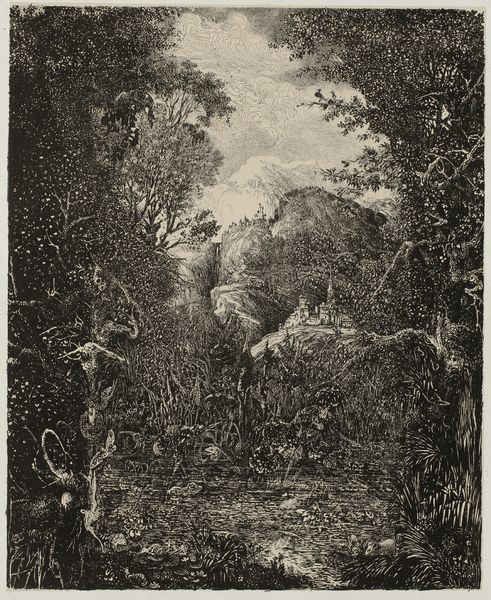

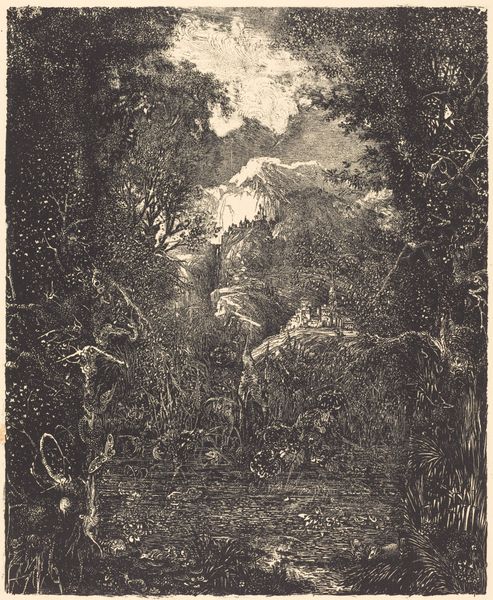

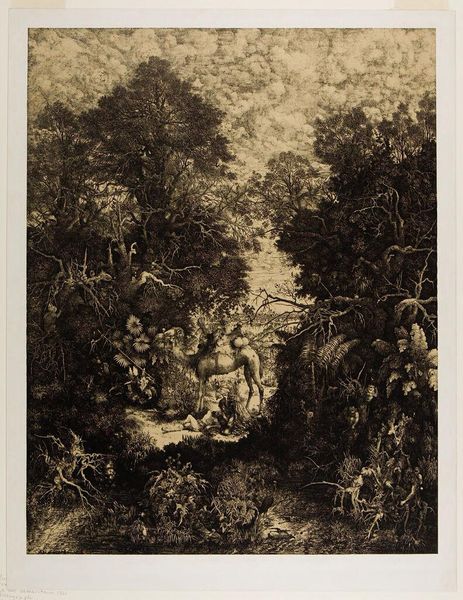

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

#

france

#

realism

Dimensions: 564 × 443 mm (image); 690 × 554 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

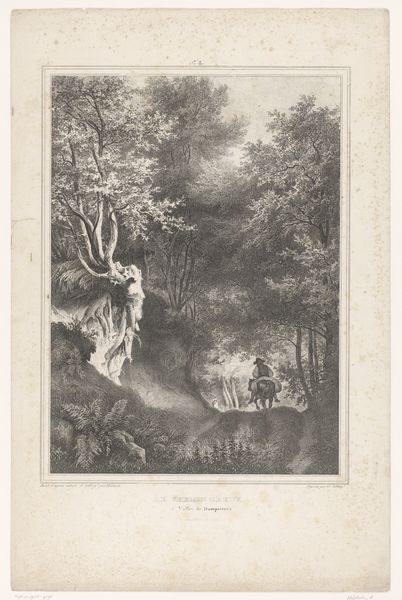

Curator: Welcome. We're standing before Rodolphe Bresdin’s 1861 lithograph, "The Good Samaritan," currently held in the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: What strikes me immediately is the almost suffocating density of the scene. The darkness, created by incredible detail in the lithographic lines, almost overpowers the central figures. Curator: Indeed. Bresdin was a master of intricate detail and employed a very distinct way of rendering the natural landscape in prints like this. Consider how the dense undergrowth frames the scene and how, even in the small print format, it evokes an expansive view. Editor: Yes, the composition definitely creates that sense of depth. And the Good Samaritan on his camel becomes almost secondary, blended in, really, within that chaotic landscape. Is that perhaps a comment on the place of morality and empathy within an overwhelming world? Curator: That is certainly one interpretation. Bresdin was a staunch Republican. One could even propose it offers a social critique by emphasizing the landscape over the individuals in a narrative normally focused on, precisely, individuals and direct action. The romantic-era landscapes—dark, cavernous, and chaotic as they appear in prints such as these—were changing alongside mid-nineteenth-century socio-political changes and turmoil. Editor: That's compelling, seeing the formal construction mirroring historical anxieties. It suggests even more complexity within the subject matter: poverty, societal collapse. Perhaps also what society *could* be? Curator: Absolutely, it embodies a narrative both of crisis and potential redemption, but certainly within the reality of the conditions. Look at the meticulous use of line, and how, as the land seems to swarm around them, the Samaritan himself is a haven within that place. This really complicates traditional notions of morality and salvation, placing them within tangible reach, where good acts occur with intentionality despite conditions and contexts. Editor: I leave this observation even more deeply moved and contemplative. I see something new each time I allow myself to dwell upon the narrative he sets forth here in tangible forms. Curator: Yes, indeed. This invites each of us to view history anew as well. It allows us to examine it with far greater intentionality and insight.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.