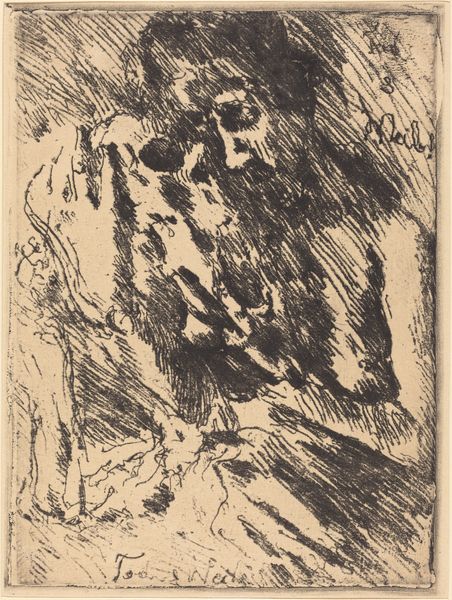

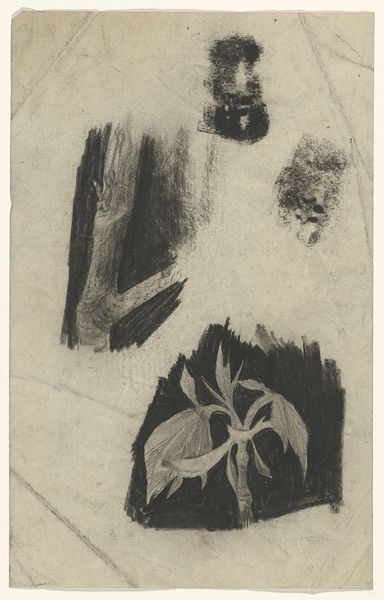

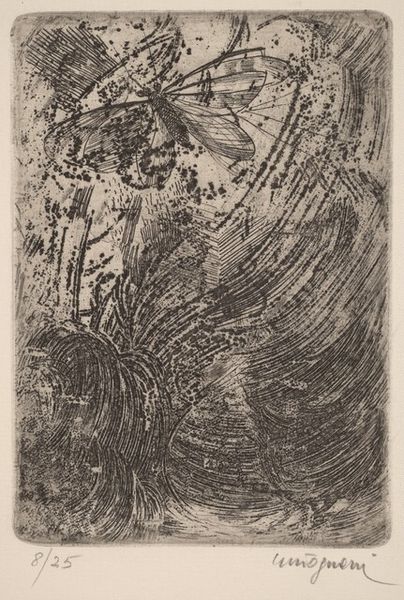

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

ink

#

realism

Dimensions: height 295 mm, width 198 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Well, this image certainly makes an impression. Morbidly intriguing. It’s giving me still-life vibes, but not the usual bright, abundant kind. Editor: This is “Dead Bird and Kettle on a Wall” by Barbara Elisabeth van Houten. It’s an etching made sometime between 1877 and 1950, a beautiful example of realism using ink on paper. It definitely captures a stark scene, doesn’t it? Curator: Yes, stark. I’d say heavy, even. All that darkness hanging… The weight of the kettle paired with the stillness of the bird creates a somber feeling. I almost feel like I can smell the metallic tang of the pot and something vaguely gamey... if that makes sense. Editor: It does. Consider the late 19th and early 20th century; realism as a movement wasn’t just about accurate depiction, but about portraying everyday life – sometimes uncomfortably so. Displaying death so plainly makes you wonder about Van Houten’s message. Is this a comment on human dependence on nature, or just an honest depiction of domesticity? Curator: I think the answer is yes and yes. Maybe that's the beauty of the print. There's an immediacy. Not just an attempt at reflecting what's "real" for viewers of the time, but a quiet observation about the dance between living and, well, *not* living. And as far as Van Houten's intent? Who knows? It feels more like she's saying "Here, *look* at this." Then steps back, silently inviting viewers to feel. Editor: Exactly. The lack of idealization typical of the era opens questions, doesn't it? Think about the burgeoning industrial revolution, disrupting traditional agricultural practices, or even urbanization drawing people from the countryside to burgeoning cities. Images like these became increasingly relevant. Curator: In a strange way, even beautiful. There's an undeniable artistry in the way Van Houten captured every detail: The kettle's curve and textures, the bird’s plumage… It makes you want to consider all that it evokes, whether it's mortality, practicality, or the often unseen facets of sustenance. Editor: Absolutely. There’s an emotional weight, prompting us to reflect on our relationship with mortality, culture, and also where it intersect—not as separate spheres but as deeply intertwined elements that are mirrored here. It reminds us how complex, nuanced and deeply resonant artworks from history can be. Curator: Thanks. I won’t look at a kettle quite the same way again.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.