Copyright: Public domain

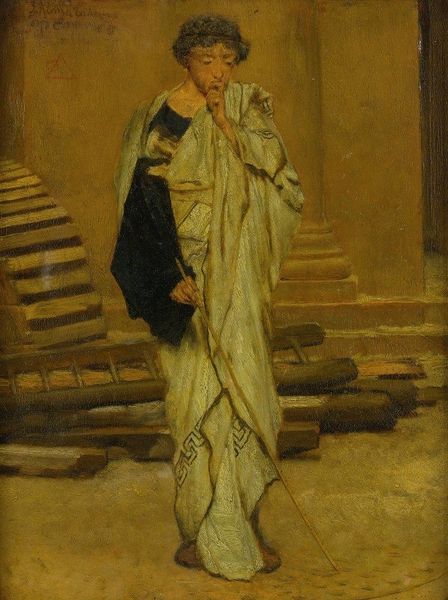

Editor: So, we're looking at "A Roman Patrician," painted by Francis Davis Millet in 1882. It's an oil painting, and the subject is this intense-looking man in a toga. What do you make of this work? Curator: Well, let's consider the materials and production here. Oil paint allows for this incredibly realistic rendering of fabric and skin. Notice the textures, almost tactile. But who was Millet catering to, and why this subject? The late 19th century saw a huge rise in industrial production and also a rise in consumerism amongst the growing middle classes in the West. Simultaneously, there was increasing social inequity. This type of history painting offered a temporary means to imagine, perhaps idealize, an era when society was highly stratified, yet the upper classes apparently maintained specific virtues such as civic duty and strength of character. Who was really consuming this, though, and what did it provide them? Editor: So it’s not just about showing history but responding to the conditions in which it was made? Curator: Exactly. Consider the commodification of classical imagery in Millet's time. Reproductions were cheap, allowing access to the perceived 'glories' of Rome, whilst conveniently masking the very different material realities faced by the majority of people living around factories. How is this different than producing cheap 'antiquities' for contemporary collectors and markets? Editor: That's fascinating, I never thought about how the making of art responds to economic structures this directly. Curator: Think about the labor involved, from the mining of pigments to Millet’s own work, versus the cost of the canvas. Who profits? It’s always embedded in a web of materials, labor, and consumption, far beyond just aesthetic considerations. Editor: I see what you mean. This portrait represents a larger set of class and economic tensions from the time. Curator: Indeed, paying attention to these dimensions enriches our understanding and moves beyond the mere 'portrayal' of a patrician, even questions what Millet intended by focusing his canvas on it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.