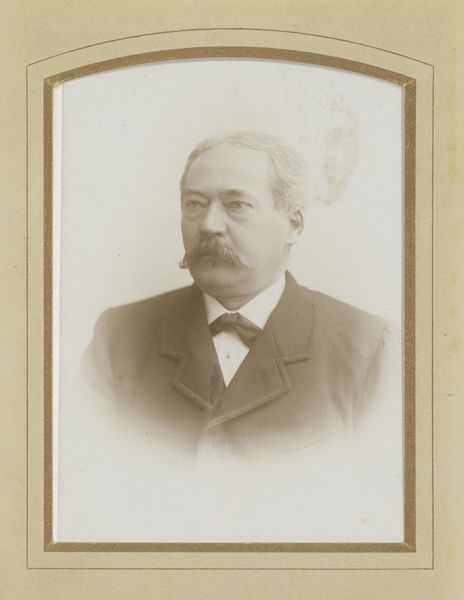

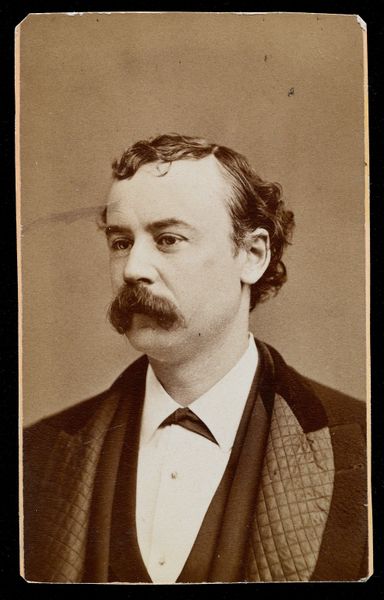

Life of Tommaso Salvini, from the Histories of Poor Boys and Famous People series of booklets (N79) for Duke brand cigarettes 1888

0:00

0:00

drawing, graphic-art, lithograph, print

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

graphic-art

#

lithograph

# print

Dimensions: Overall (Booklet closed): 2 3/4 × 1 1/2 in. (7 × 3.8 cm) Overall (Booklet open): 2 3/4 × 2 7/8 in. (7 × 7.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

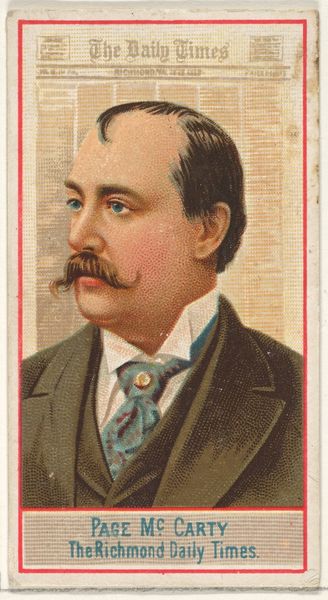

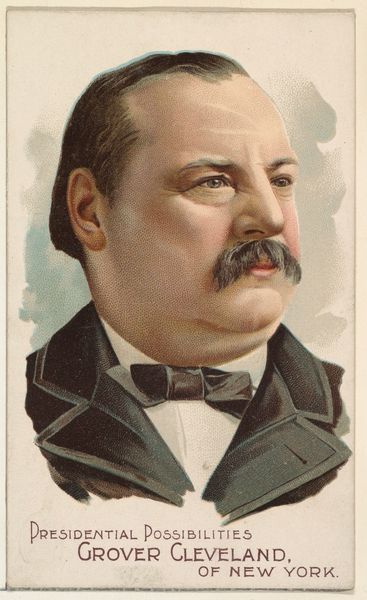

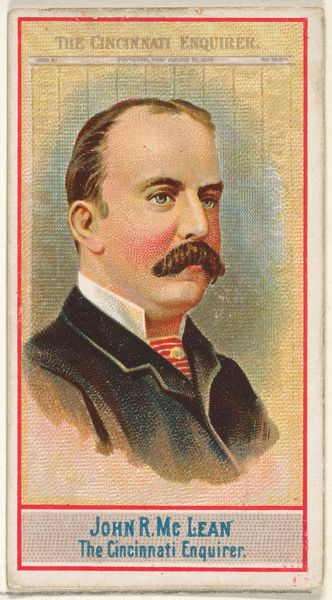

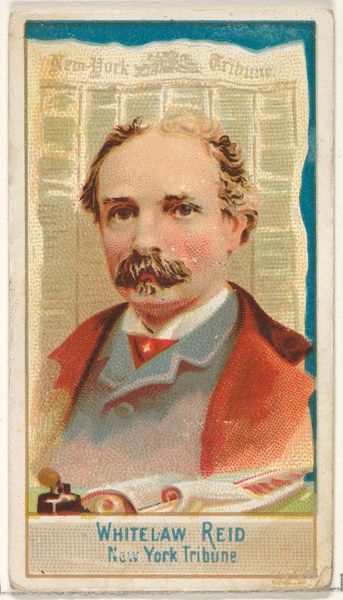

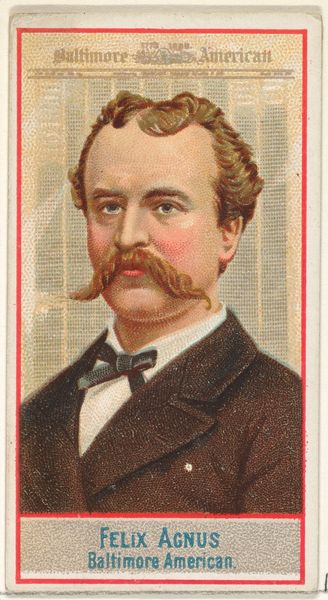

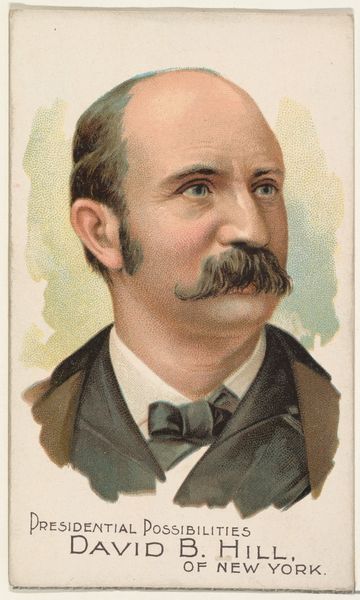

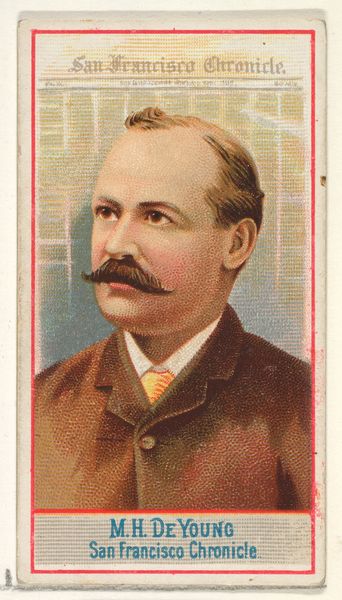

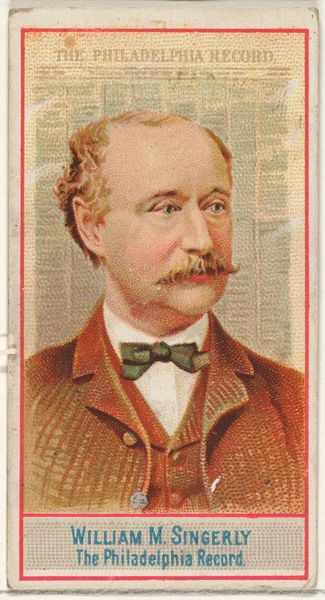

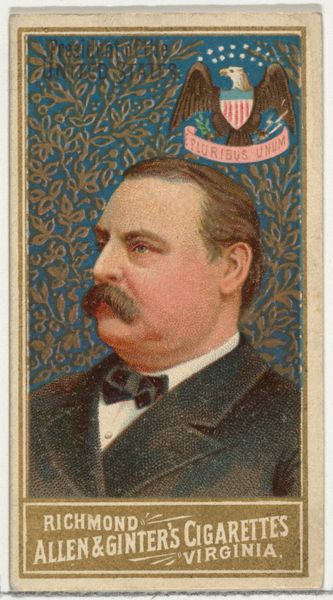

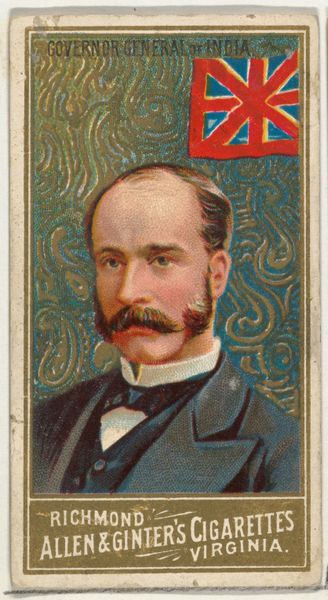

Curator: Here we have a portrait from 1888: "Life of Tommaso Salvini, from the Histories of Poor Boys and Famous People series of booklets" by W. Duke, Sons & Co. It is a lithograph, part of a series designed to be included in cigarette packets. Editor: Immediately, the contrast between the 'Poor Boys' element and the famous portrait strikes me. There's a strange glamour and desperation implied at once. The portrait feels strangely intimate because of the scale, and yet the medium also reduces him to a commodity. Curator: The intent here, it seems, was to inspire upward mobility – what is considered in the US as "pulling yourself up by your bootstraps"— Salvini himself embodies the symbol of aspirational ascent, going from humble beginnings to a famous Shakespearean actor. It would speak volumes to consumers then, particularly new immigrants trying to negotiate identity and class. Editor: So the implicit message: 'Smoke Duke cigarettes, be like Salvini'? The construction of these ideals through an endorsement, through something as potentially destructive as cigarettes, feels exploitative and telling. It makes one wonder how the cultural and racial stereotypes worked their way into these kinds of popular media. Who, precisely, were these “poor boys,” and who got to be "famous people"? Curator: Absolutely. The "poor boy" image, as it is embedded, is interesting when we consider what the intended target of these cigarette booklets would have been. Here, the symbolic power is a blend of entertainment and pedagogy for new customers. Salvini’s serious demeanor might even confer a sense of high culture or education upon the smoker! Editor: A manufactured connection indeed. The use of Salvini in this context reveals the late 19th-century commodification of fame. But also the narratives around fame itself. The booklet seems to propagate this "rags to riches" story as an acceptable or laudable version of social mobility. Curator: It certainly complicates any simple interpretation of "historical document", doesn’t it? It layers in ideas of consumerism, aspiration, and social hierarchy. The portrait is more than just an image; it’s a coded message about society. Editor: Exactly, these commercial images offer incredibly valuable insights into social engineering, especially the production of racial and economic others in the late 19th century. Curator: Considering that, I don’t think I’ll look at cigarette cards in the same way again! Editor: Nor will I! I will always look beneath the surface, because these booklets were not just adverts, but vehicles of social ideology.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.