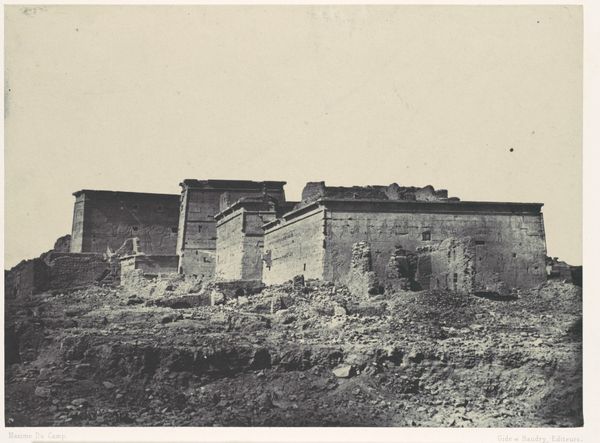

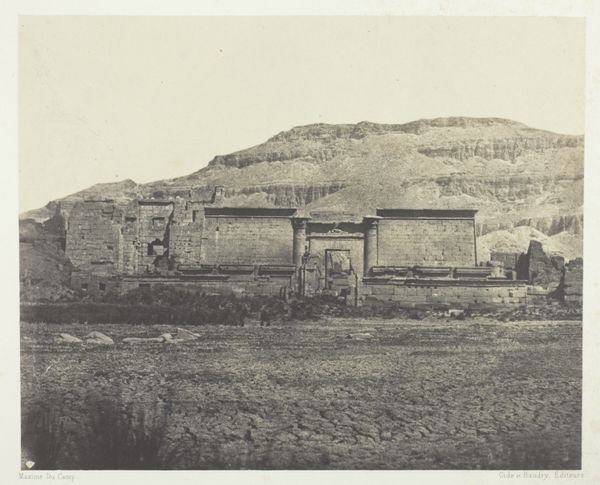

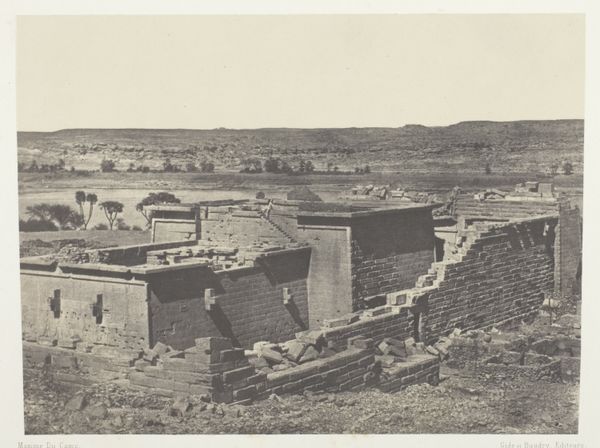

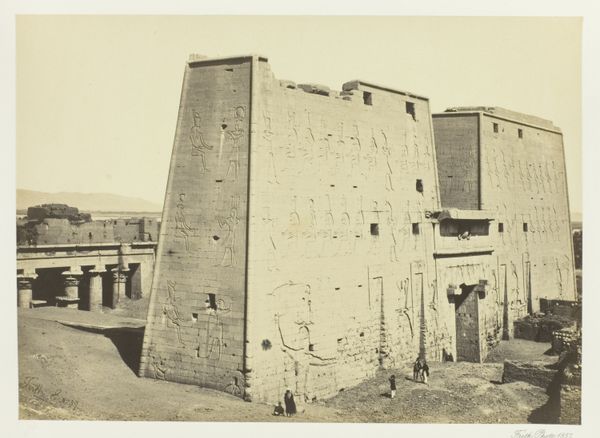

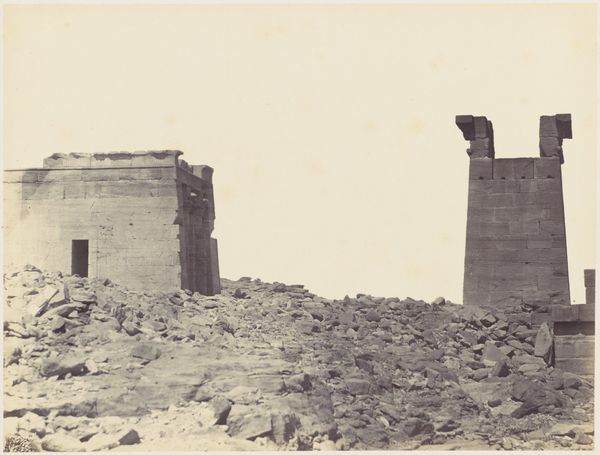

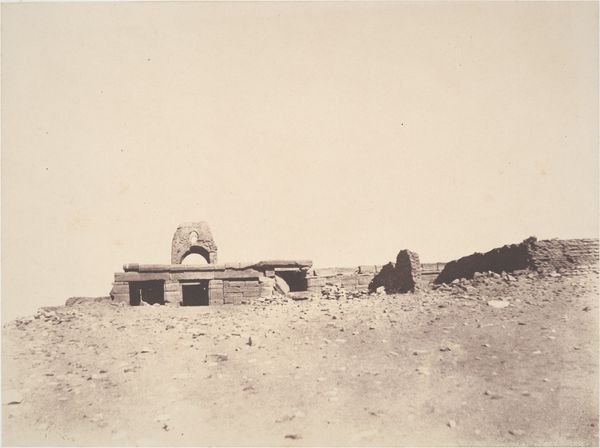

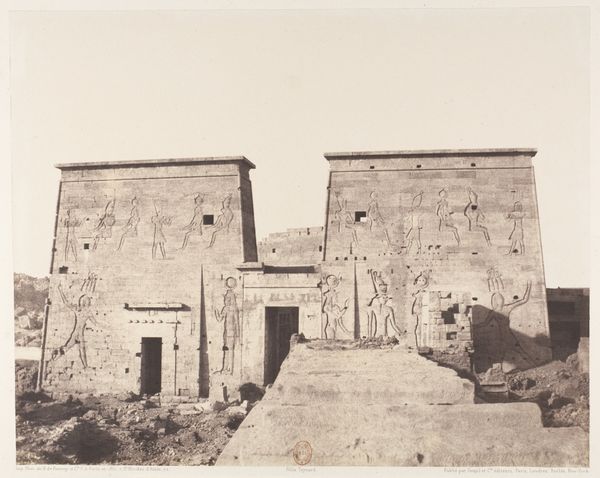

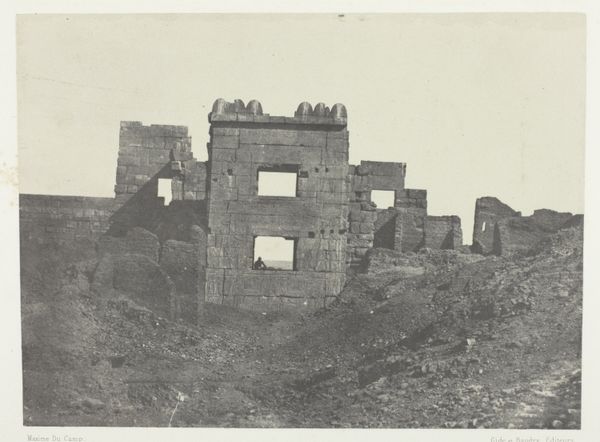

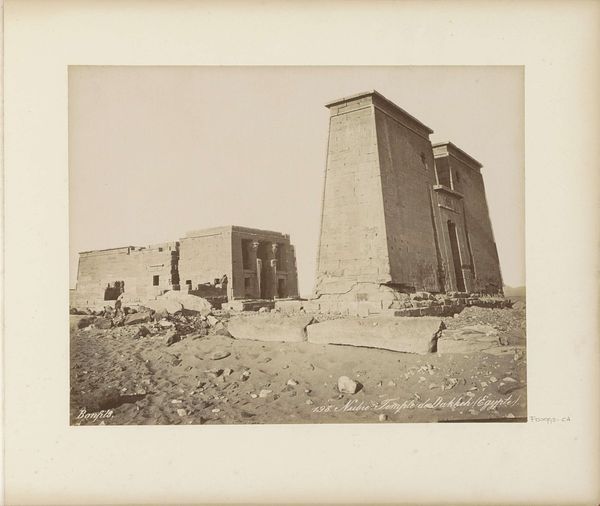

Temple De Dakkeh (Ancienne Pselcis); Nubie Possibly 1849 - 1852

0:00

0:00

print, etching, paper, photography

# print

#

etching

#

war

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

paper

#

photography

#

egypt

#

natural palette

#

realism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: 16.6 × 21.1 cm (image/paper); 30 × 42.9 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. Today, we’re looking at a photograph by Maxime Du Camp, likely taken between 1849 and 1852. The piece, titled "Temple De Dakkeh (Ancienne Pselcis); Nubie," captures a ruined temple in Nubia, Egypt. Editor: My first thought is how powerfully austere it feels. The composition emphasizes the temple's geometric structure, a series of stacked rectangular forms under a bleached sky. The limited tonal range really throws those blocky shapes into sharp relief. Curator: Indeed. Consider the historical context: Du Camp accompanied Gustave Flaubert on a journey to Egypt, commissioned by the French government. Their travels, and photographs like these, served to document and, arguably, legitimize France's burgeoning colonial interests in the region. This documentation participates in a visual language that supported Western imperial narratives. Editor: Yes, but looking at the photograph itself, there's such clarity in the etching technique. See how the light rakes across the stone, accentuating every line and crevice. This almost hyper-real quality intensifies the building's monumentality. Curator: Yet, there's also a melancholic air. These temples signify not just a lost civilization but the power dynamics inherent in its rediscovery and representation by a Western photographer. Whose gaze truly frames this "ruin"? And how does that shape our perception of Egypt and its people? The sepia tones also suggest the faded glory but equally a historicizing of a nation and people from the view point of colonial travelers. Editor: I can see your point. It raises the question of intention. Was Du Camp aware of that gaze, or was he purely interested in rendering an architectural structure with precision? Semiotically, the stark monochrome converts into a sign of Western knowledge encountering a formerly hidden world. Curator: Ultimately, this work exemplifies the complexities of viewing historical documentation through a critical lens. While offering us visual data, it also reflects the socio-political climate of its time. The act of photographic capture in itself was intertwined with power, politics, and identity. Editor: Right. So much of how we see is baked into the image itself. Du Camp’s photo serves as more than simply a portrait of a place; it provides a way to interpret art with politics and history combined. Curator: Precisely. These nuanced readings help us unpick the layers of historical images such as this one. Editor: Yes, a testament to how an image—a visual artifact—can continue to shape dialogues on representation and power today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.