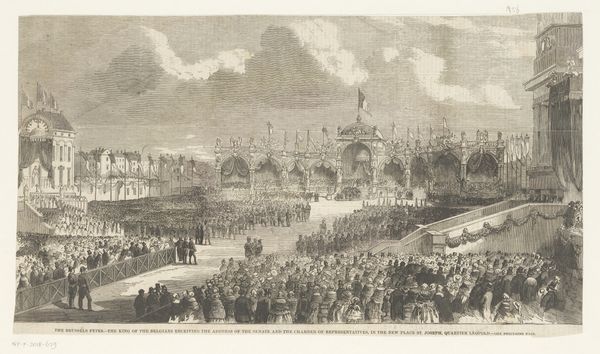

Dimensions: height 254 mm, width 363 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: So, here we have an engraving by P. Blanchard from 1855 titled, "Queen Victoria Arriving at the Train Station of Boulogne." The pomp! The circumstance! It's so visually busy, isn't it? Editor: Over the top doesn't even begin to cover it. It strikes me as incredibly formal, but beneath all the ceremony, I can’t help but think about the sheer labor it must have taken to put all this on, the backbreaking work of setting up those arches and waving those flags. Curator: Oh, absolutely! And those arches, the temporary architecture, the fleetingness of it all in the face of such human effort, just blows my mind. They're like stage sets for a single, brief performance. All that to show off to a monarch visiting a neighboring nation! Editor: And Blanchard chose engraving. Think about it: the deliberate process of transferring this fleeting event into a reproducible image. Each line carefully etched. It makes me wonder about his perspective; was he commissioned? What were his motivations? And how would this reproduction be consumed by the British vs the French at the time? Curator: Intriguing question! But consider the deeper narrative— the queen, a symbol of her nation, venturing onto foreign soil, becoming both a spectacle and spectator. It's almost like a mirror reflecting back at England, asking: “How do we appear to the world?” Do you feel that sense of curiosity embedded here? Editor: Definitely, but let’s not get lost in monarchical symbolism alone! The work's essence lives and dies by the availability of print, affordable paper, and a culture that hungered for images. Queen Victoria wouldn't have nearly as much relevance today if it weren’t for all of this circulation and its inherent potential. Curator: Right, right, because that accessibility completely shifted the art world and the concept of ‘high art.’ Before that kind of access, everything was literally monumental— sculpture, cathedral, the grand scale oil paintings destined for some palazzo walls. A humble print can actually capture such pomp— so egalitarian in that sense. Editor: It is. To truly appreciate art we need to interrogate production, distribution, and consumption. It's all interconnected, just as it was back in 1855 when this print was meticulously created. Curator: So, thank you P. Blanchard for making me think way too deeply about national ego and travel anxieties. It’s both an awkward and tender dance to view oneself, or at least, your nation through a neighboring country’s pomp and ceremony. Editor: Agreed! Considering the social backdrop offers much deeper understanding. It really moves away from art for art's sake, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.