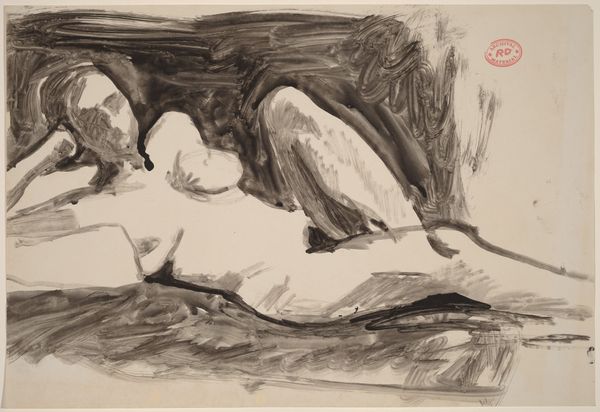

![Untitled [female nude lying on her side] by Richard Diebenkorn](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzMyMmZjMzEwLTZhYjEtNGE2ZS04ZGYzLTlkMTk0OTlkMDNiNy8zMjJmYzMxMC02YWIxLTRhNmUtOGRmMy05ZDE5NDk5ZDAzYjdfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

bay-area-figurative-movement

#

pencil

#

nude

Dimensions: overall: 35.2 x 42.9 cm (13 7/8 x 16 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

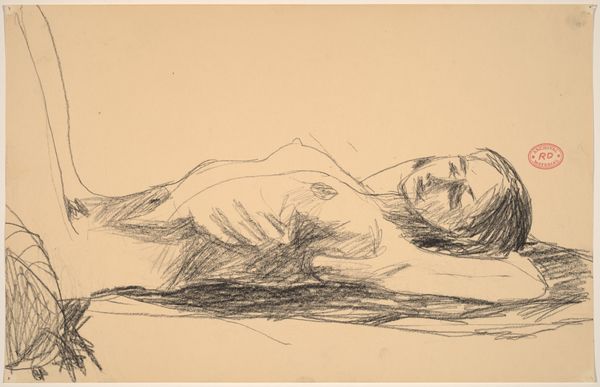

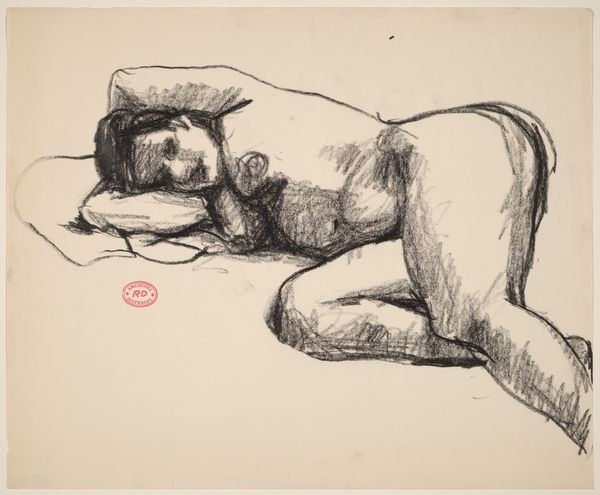

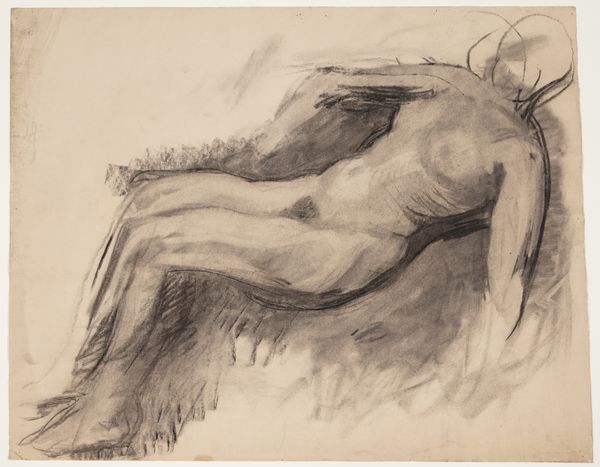

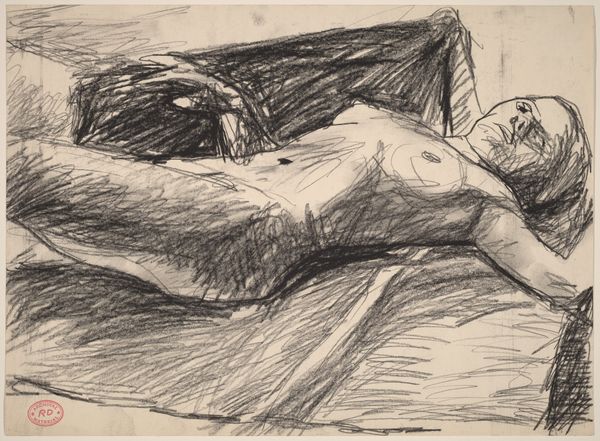

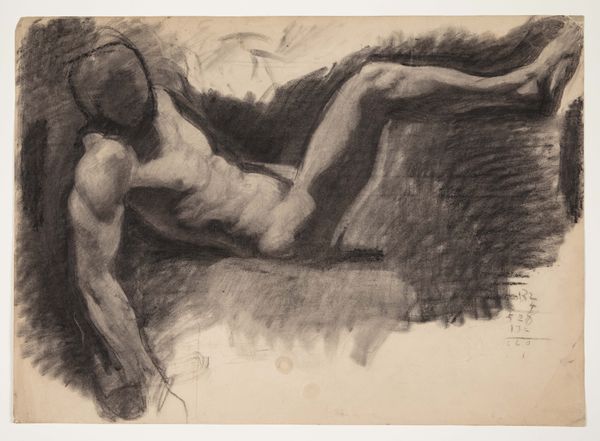

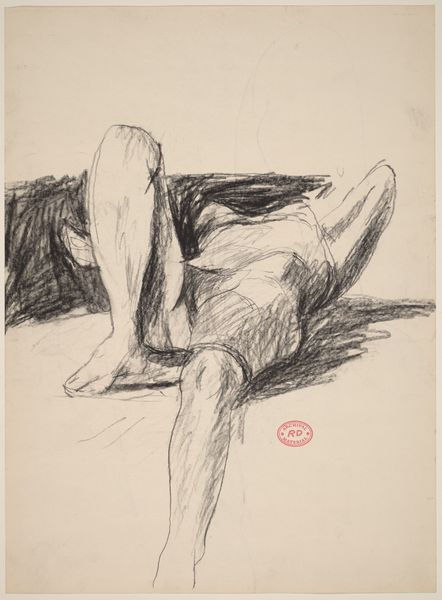

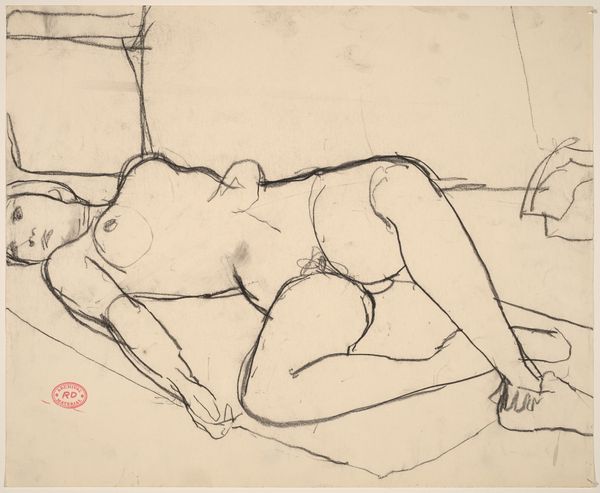

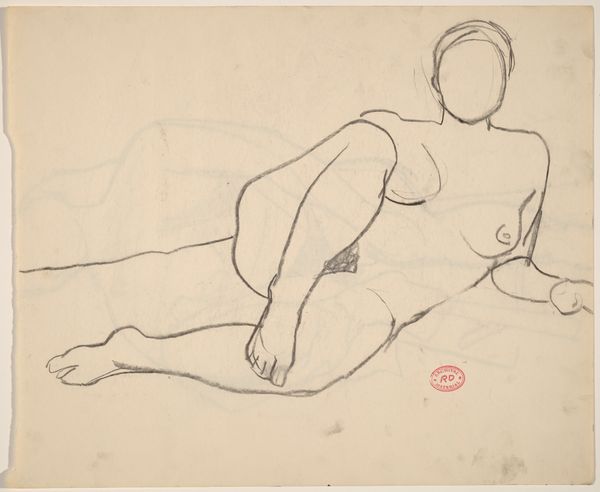

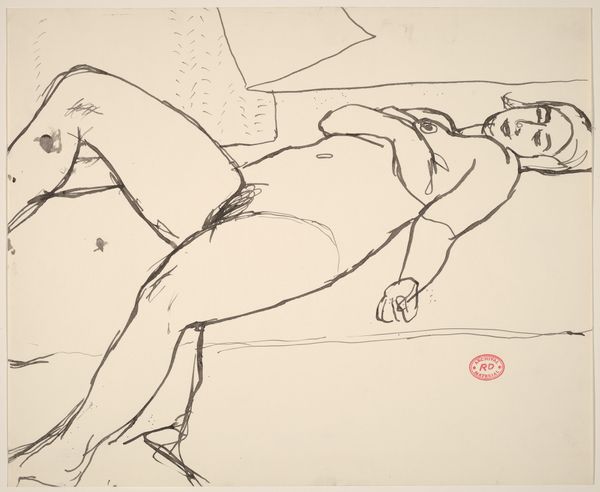

Curator: This is an untitled drawing by Richard Diebenkorn, created sometime between 1955 and 1967. It depicts a female nude lying on her side, rendered in pencil. Editor: My first impression is one of intimacy, almost a vulnerability. The sketch feels very immediate, like a private moment captured on paper. Curator: Diebenkorn was deeply engaged with the human form throughout his career, constantly exploring and redefining the possibilities of representation. He used pencil and ink relentlessly. What tools do the depictions of women enable or challenge when it comes to process and reception? Editor: Indeed, that is central to how this work situates within discussions around the male gaze, wouldn’t you say? Here is the female form observed but also seemingly at rest, unaware. It’s almost as if the viewer is granted access to a hidden realm, posing ethical questions. Curator: I’m drawn to the materiality of the drawing itself. The smudging and layering of the pencil lines – it is obvious that this work required much reworking. The roughness invites questions regarding the commodity status that this art could have; it instead conveys intimacy in a medium typically used for studies. Editor: Precisely. And the drawing style also has that interesting tension, doesn't it? It looks unfinished in its loose lines, but simultaneously is confidently formed. Diebenkorn really captures the weight of the body with such apparent simplicity. The subject has become iconic, yes, but also… familiar. Curator: To think of the source of the pencils themselves, their provenance; were these readily available materials? This speaks to issues of production and labour and its influence on the outcome of a composition that conveys serenity. Editor: I’d like to think too about Diebenkorn's influences, we've spoken of materials as enabling process and creation; so, what was he reading, thinking, what discourses informed his understanding and translation of the human form? And the models, who were they and what can this history and image tell us about these times, places and the hierarchies that prevailed then. Curator: That all becomes tied to the drawing's significance today. The social conditions always shape the reception. Editor: And how we continue to see—and interpret what is deemed worth representing and how. Thank you for your consideration on this reading.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.