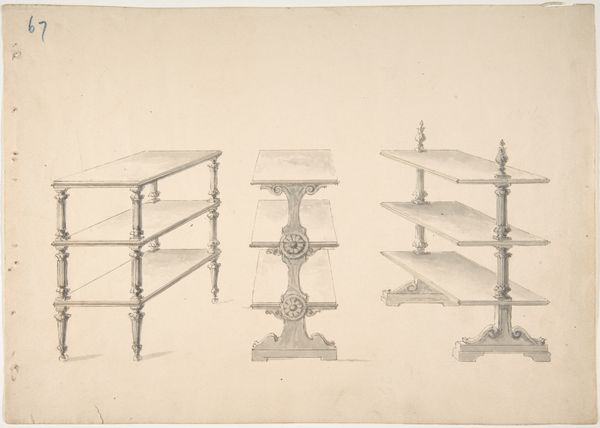

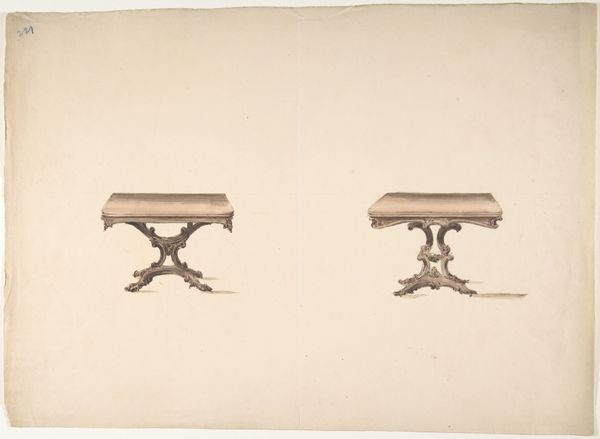

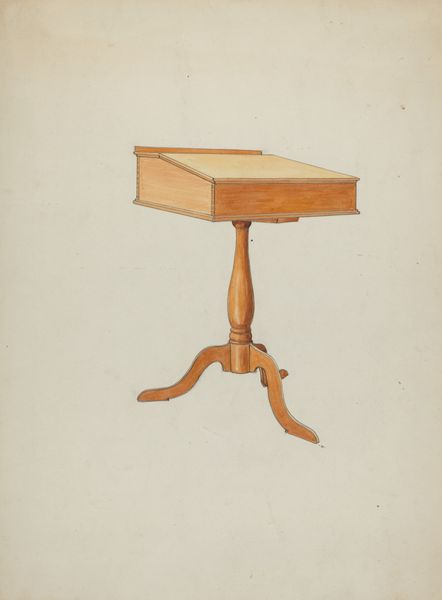

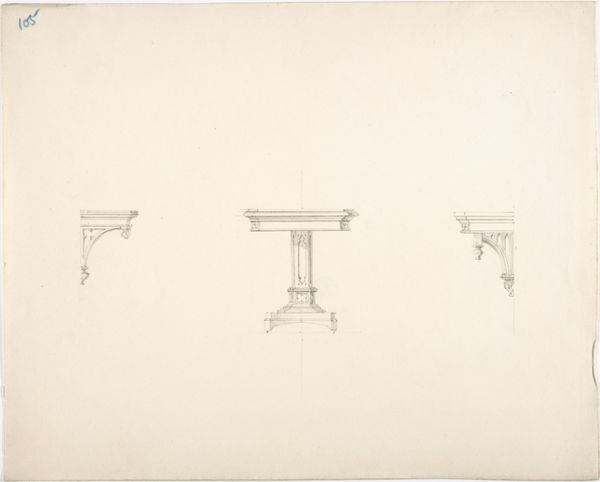

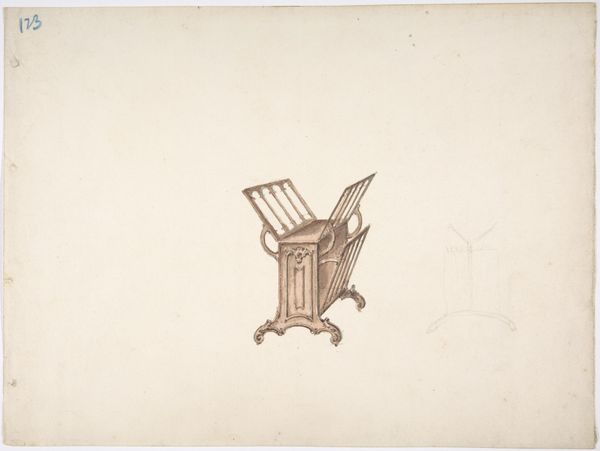

drawing, print, watercolor, pencil

#

drawing

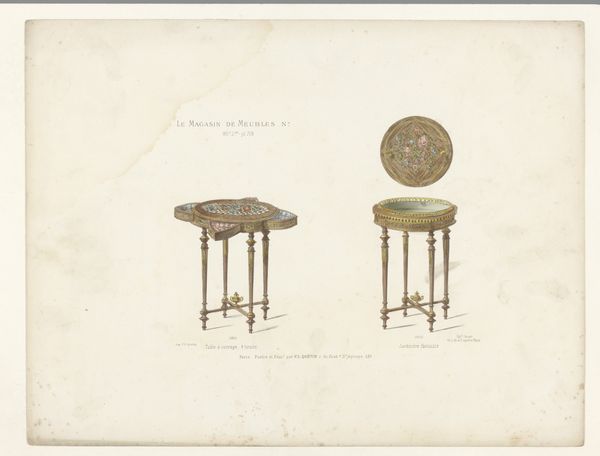

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

furniture

#

etching

#

watercolor

#

geometric

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

watercolor

Dimensions: sheet: 9 1/8 x 11 7/8 in. (23.1 x 30.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have an anonymous drawing, "Design for Two Bookstands on Casters," dating from between 1800 and 1850. It combines pencil, watercolor, and etching. I’m struck by the almost fragile elegance of the designs; what are your thoughts on this, particularly within the historical context? Curator: Well, it’s fascinating to consider this drawing as a document reflecting societal shifts. During this period, burgeoning literacy rates intersected with evolving ideas about domesticity and gender roles. These bookstands weren’t merely functional objects, but statements about the owner's access to knowledge and cultivation. Consider who might have used these: were they designed for women of leisure, whose access to education was simultaneously celebrated and constrained? Editor: That’s a perspective I hadn't considered. The delicacy of the design almost masks those potential social implications. So, do you think the 'Romanticism' tag assigned to the artwork contributes to that reading as well? Curator: Absolutely. Romanticism often idealized the domestic sphere, and the artistic inclinations of women. But it's also crucial to acknowledge that this ideal was often predicated on excluding marginalized voices. The very act of carefully rendering these bookstands, using delicate watercolors, becomes an exercise in defining and maintaining social boundaries. Who had the resources, the time, the permission, to engage in such creative pursuits? Editor: So the beauty of the drawing and its seemingly harmless subject actually masks layers of social commentary. Curator: Precisely. It invites us to question whose stories are being told, and whose are being omitted, when we study these objects and their cultural context. And also how the intersectionality of class, gender, and access shaped the creation and consumption of even the most seemingly benign designs. Editor: That's given me a lot to think about regarding how we interpret these kinds of historical pieces. It’s made me rethink the potential narratives embedded within the design itself. Curator: And that’s the exciting challenge of art history, isn’t it? To constantly re-evaluate and to see it as connected to social structures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.