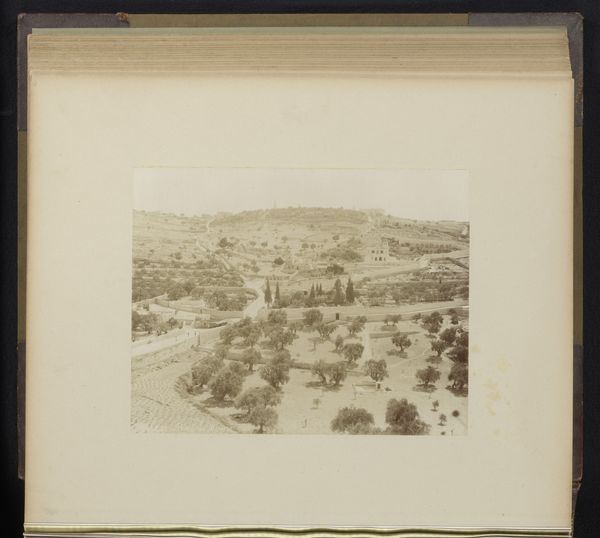

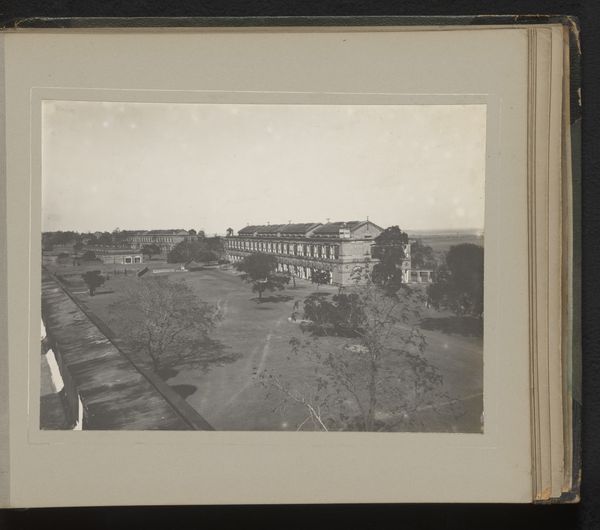

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

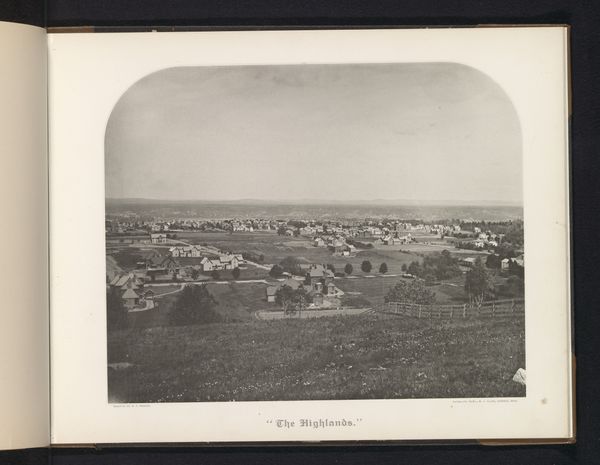

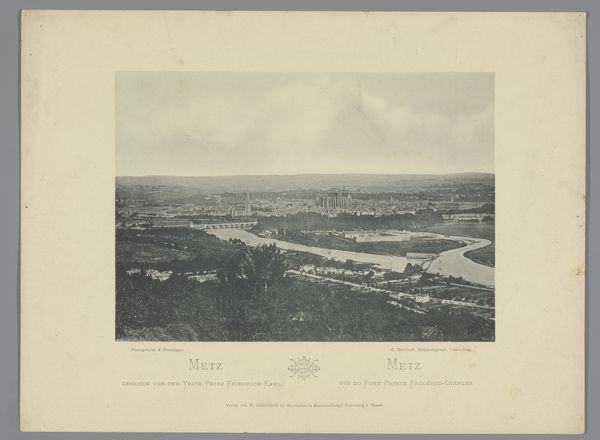

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 218 mm, width 277 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

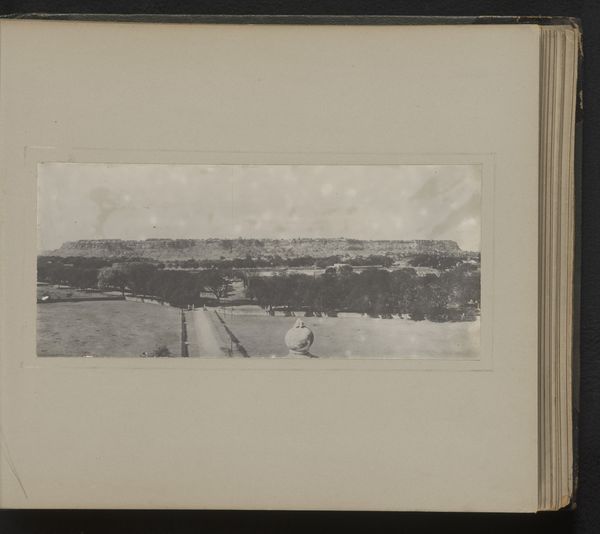

Curator: What a serene view. The photograph before us, "Gezicht op Jeruzalem vanaf de Scopusberg," taken by F\u00e9lix Bonfils between 1867 and 1885, presents a panoramic vista of Jerusalem from the vantage point of the Scopusberg. The delicate tonality is characteristic of gelatin-silver prints of this era. Editor: It does feel quiet, doesn’t it? The city is just a muted collection of buildings on the horizon, almost like a mirage. I'm struck by how empty the foreground appears. A solitary figure seems dwarfed by the scale of the landscape, emphasizing the isolation and distance from the subject. Curator: That’s precisely what many photographers during this time aimed for, capturing a scene’s sense of the sublime alongside, or perhaps in conjunction with, a more grounded interest in documentation. These images were extremely marketable. Bonfils was known to sell many photographic prints, playing into orientalist trends, offering glimpses of faraway lands to a Western audience hungry for these sorts of representations. We are viewing this at the Rijksmuseum, and the institution plays a role in framing how these artworks continue to be appreciated today. Editor: That's an interesting angle, especially thinking about the photographic process involved. What equipment was necessary to produce these works and make this distribution viable? It seems as if an image like this, of what at first glance appears empty, must in truth involve lots of people and mechanisms. Curator: Absolutely. Producing images on location during that era demanded extensive equipment. Bonfils, being based in Beirut, managed a studio with considerable resources. He used relatively large glass plate negatives, and developing facilities in the field were likely very primitive by our standards, relying on sunlight for printing. Beyond technical logistics, this sort of picture-making involved local labor too. He probably hired assistants who prepared chemicals, carried equipment, and even scouted suitable locations. Editor: The material realities of production can really contextualize the photograph's status as more than just a "window" onto the scene and instead emphasizes how complex are the layers involved. Understanding the mechanisms of its creation and the political factors involved help give it a greater historical and societal significance, despite that air of remoteness it communicates. Curator: Precisely. Looking at the image beyond its mere aesthetic qualities reveals the fascinating intricacies of image production and consumption in the late 19th century. I am always humbled by what an image can reveal. Editor: Agreed. Now, after all that discussion, the view seems anything *but* silent.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.