print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

realism

#

building

Dimensions: height 382 mm, width 560 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

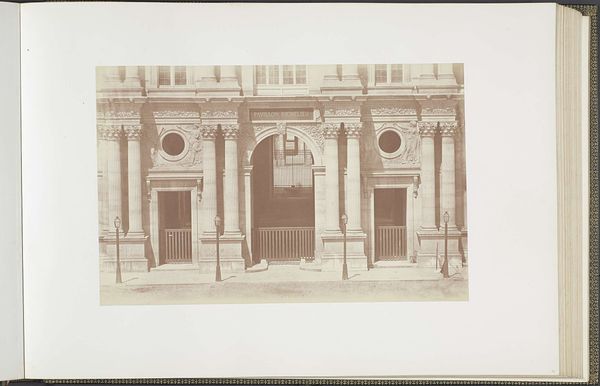

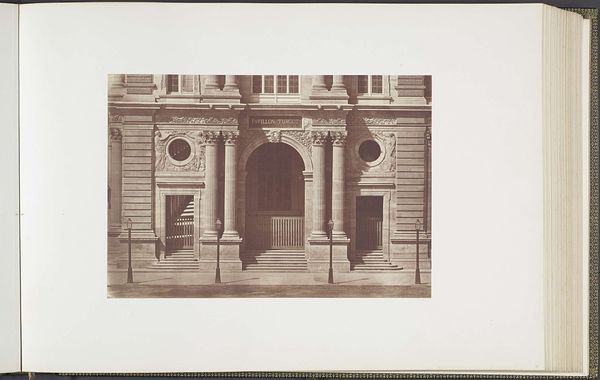

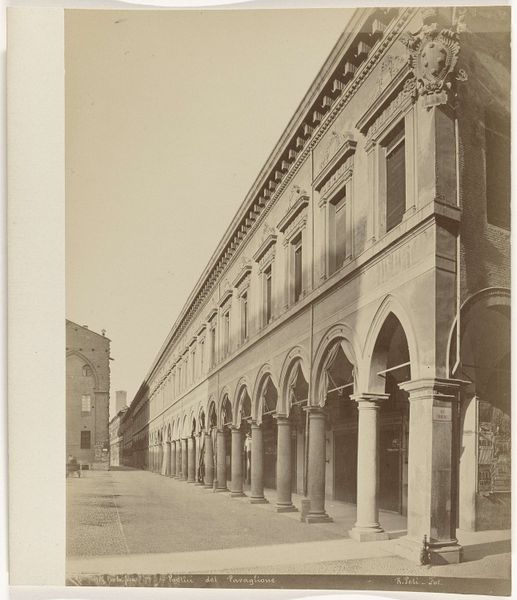

Editor: Here we have Edouard Baldus’s photograph, “Begane grond van het Pavillon Sully in het Palais du Louvre,” taken around 1857. It's a gelatin-silver print. I'm immediately drawn to the incredible detail and the play of light and shadow across the building's facade. What can you tell me about this piece? Curator: This image presents an interesting point when thinking about the cultural position of photography in the 19th Century. Baldus has carefully created a document of a modernising Paris; he has foregrounded the industrialised process behind this highly ornamented image. Look at how the architecture and photographic technology relies on extraction and labor. Editor: So you're saying it's not just a record of the building, but a statement about production itself? Curator: Precisely. Photography at the time was often contrasted with painting and sculpture. Photography's inherent reproducibility meant it wasn’t considered unique or high art in the same way. Yet, images like this draw attention to the vast social organisation required for the creation and consumption of grand buildings. The photographic print, mass produced from chemical and industrial processes, documents this architectural monument of stone and labour. Editor: It's amazing how a photo of a building can tell us so much about the society that built it, and about the debates concerning the nature of art in that period. Curator: Exactly. We tend to forget how ubiquitous materials and processes shape what we understand and value as art. Editor: Thanks, I will never perceive photographs of buildings as 'simple records' anymore. Curator: I'm glad I could help!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.