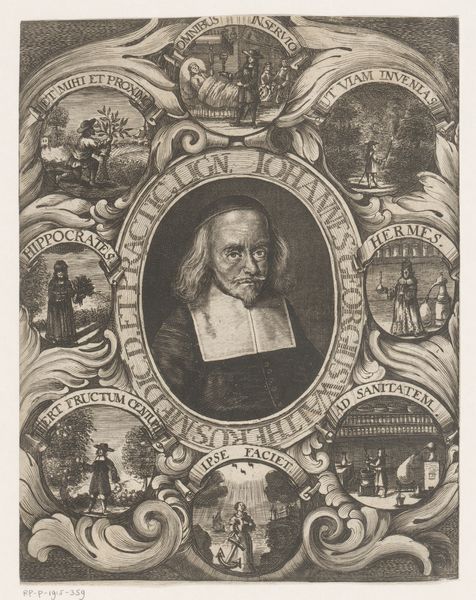

print, etching, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

etching

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 407 mm (height) x 322 mm (width) (plademaal)

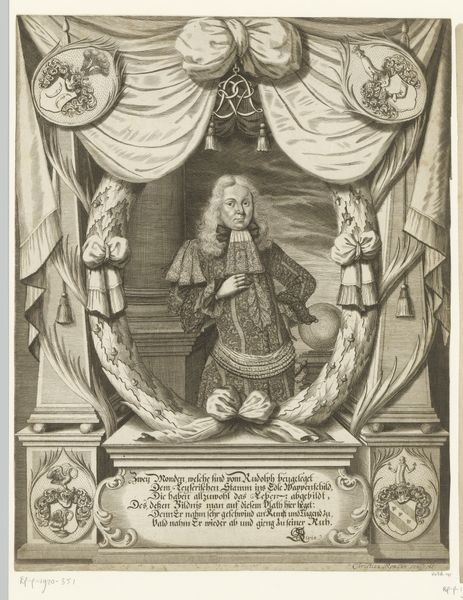

Editor: Here we have "Wentzel Rothkirch. Illustration til ligprædiken," an engraving and etching made in 1657 by Albert Haelwegh. The portrait is surrounded by smaller circular images, and there's so much symbolism packed in...it feels almost overwhelming. What's your take? Curator: Overwhelming is a good word for it. Consider that such elaborate memorial prints were often commissioned by or for the family of the deceased, meant to publicly commemorate their virtues and status. It's an intensely social act. What stands out to you beyond the general symbolism? Editor: Well, the central portrait has this imposing figure looking directly at us, holding what seems to be a commander's baton. And there are all sorts of objects below him. Are those his personal effects? Curator: Perhaps. We see an owl, an elephant figurine, some military gear…likely all alluding to aspects of his life, roles, and perhaps even aspirations. But remember, the print functions as public art. How would these images communicate specific messages about Rothkirch to his intended audience? Editor: So, the military gear suggests his role in the army. The owl probably refers to wisdom. And what about those circular images surrounding the portrait? Curator: They could represent different stages of life or perhaps allegorical figures associated with virtue or mortality. Death was very public during this era; how could prints like this shape collective memory and social standing? Editor: I see. It's not just a personal memento, but also a carefully constructed statement aimed at shaping public perception. This really makes me think differently about portraits! Curator: Exactly. Art isn’t created in a vacuum; it’s always intertwined with social, cultural, and even political currents.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.