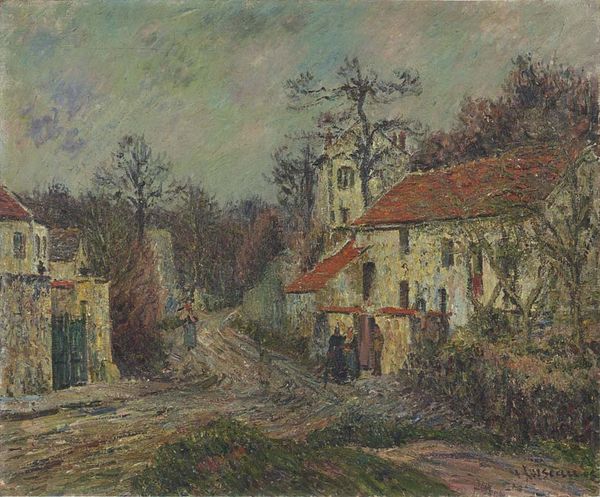

Copyright: Public domain

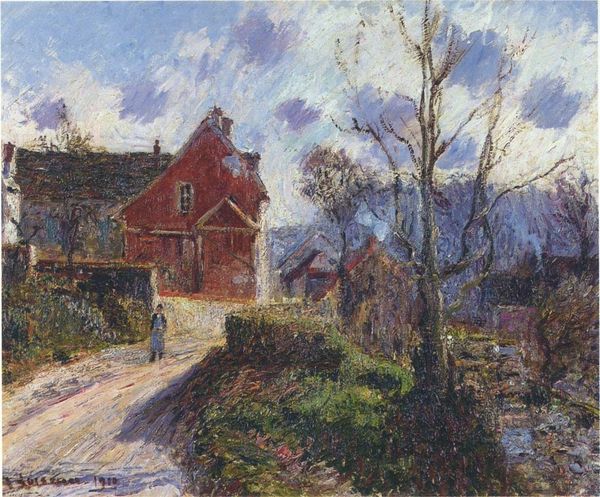

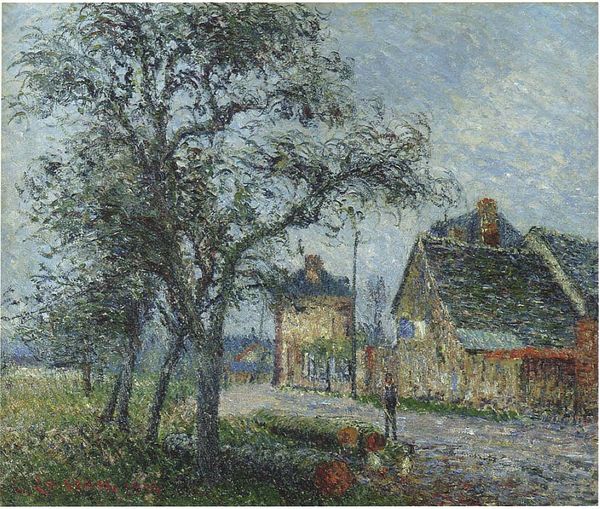

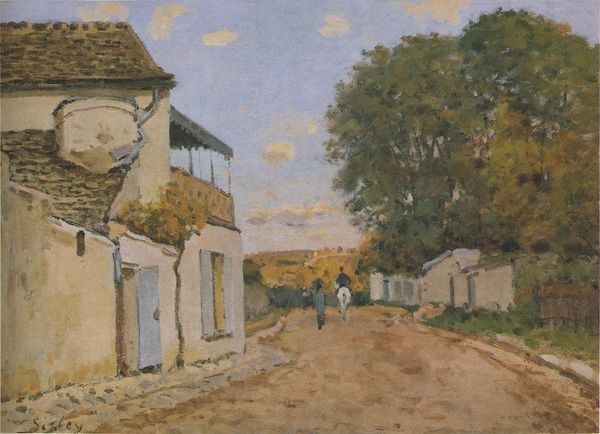

Curator: Here we have Gustave Loiseau's "Road to Versailles," painted circa 1910. The medium is oil on canvas, created outdoors, capturing the light and atmosphere in that fleeting moment. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by how peaceful it feels. There's this hazy quality to the light that softens everything, almost like looking at a memory. It evokes a sense of quiet, rural life but it almost looks like a stage set. Curator: Indeed, the artist's handling of the paint lends to that softness you observed. He uses short, broken brushstrokes in varying directions to create a textured surface, not to meticulously capture every detail, but rather the overall impression of light filtering through trees onto buildings. Consider how the very process replicates that momentary visual experience. Editor: And that experience is so intertwined with its social context, right? Versailles wasn't just some random locale. It was a symbol of absolute monarchy, aristocracy, extreme privilege. Painting the "Road to Versailles" in 1910, when those powers were waning, makes you consider class dynamics, revolution. Curator: Loiseau's work certainly operates in dialogue with its predecessors and contemporaries in landscape painting, such as the Barbizon School, who also emphasized working "en plein air", from direct observation. In doing so, however, he departs slightly; we have more signs of human presence than the previous generation and a new rendering style. Editor: The artist doesn't completely erase signs of modern life or erase people as workers and members of the public. Instead, he invites us to consider how place and identity intersect. You have this landscape associated with luxury, yet the painting captures a slice of everyday life for regular citizens who likely traveled the very road it depicts, too. What kind of visual experiences did these residents have, then, while seeing signs of aristocracy on a regular basis? Curator: And we might ask about the materiality of those structures. Consider how labor played a role in sourcing and shaping the stones, quarrying them, and erecting them in a given way to symbolize class, to serve a clear political purpose. The same can be asked for the more humble homes represented nearby. Editor: Yes! Bringing the discussion back to materials shows how these were then transformed to reflect power dynamics that defined the social hierarchy in early 20th century France. Thanks, Gustave, for putting those power structures into perspective on that sunny afternoon. Curator: A potent reminder that even in what seems like the most bucolic setting, materiality, power and labor are ever-present elements, informing our very perspective.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.