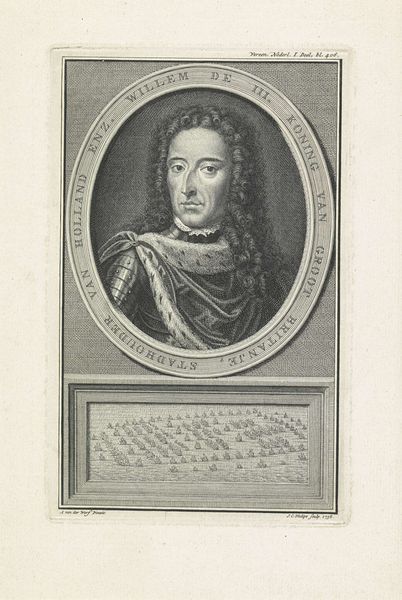

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 265 mm, width 182 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Right, let's dive into this rather intriguing portrait. What we have here is an engraving from 1729 by Bernard Picart, titled "Portret van Willem III, prins van Oranje"—William III, Prince of Orange, to those of us not fluent in Dutch! It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: You know, the first thing that strikes me is how much personality they managed to capture with just lines. He’s got this, like, half-amused, half-disapproving look, doesn't he? Almost like he's judging my outfit! And the wig, the endless wig... it's sort of its own character in the portrait. Curator: Absolutely. And considering Picart was working well after William III's death in 1702, this image participates in the construction of a particular kind of historical memory. It aligns William with ideas of Dutch and British power and Protestant identity during a period of intense political and religious tension. His legacy became a crucial component of national narratives. Editor: So, it's like... propaganda, but fancy? The details, like the armor and the ermine trim, it is clearly about signaling power. But somehow, it also feels a bit… melancholic. Maybe it’s the black and white; maybe it’s just imagining being trapped in that wig all day! Curator: Well, keep in mind the Baroque style prevalent at the time. Think about the visual language of Dutch Golden Age painting - the status, the wealth. Picart is very consciously positioning William III in that historical context, emphasizing continuity and legitimacy. Engravings like this one were widely circulated. They served to create a visual culture connecting rulers and the ruled across vast distances. Editor: Distance, right. So it's about manufacturing a shared experience with the guy who makes the rules, regardless of how far you are from him, physically or maybe even culturally? The details invite close inspection, all those tiny etched lines making up his features, the folds of the cloak. It’s incredibly intricate when you get close, really kind of mind-blowing in a pre-digital kind of way! Curator: Precisely. The dissemination of these images facilitated engagement—and helped form, arguably, an idea of collective belonging, or at least submission to that "old engraving style" of power and belonging! Editor: It is definitely interesting how a historical portrait like this also sort of reflects contemporary issues like nationalism and the way that we continue to craft narratives about our leaders. All in all, he’s grown on me. He doesn't only look as though he is disapproving of my outfit, perhaps I can win him over. Curator: Indeed, it forces us to think about who gets remembered, how they get remembered, and who gets to do the remembering, even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.