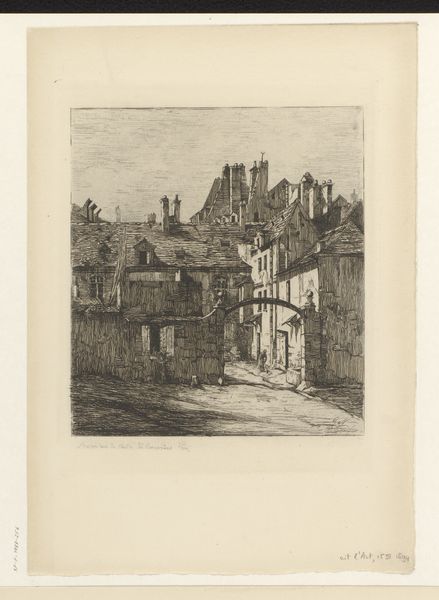

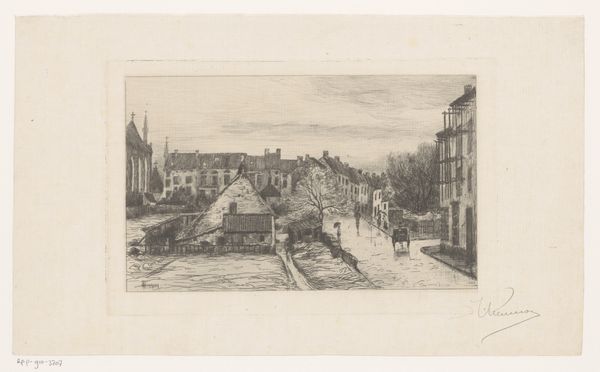

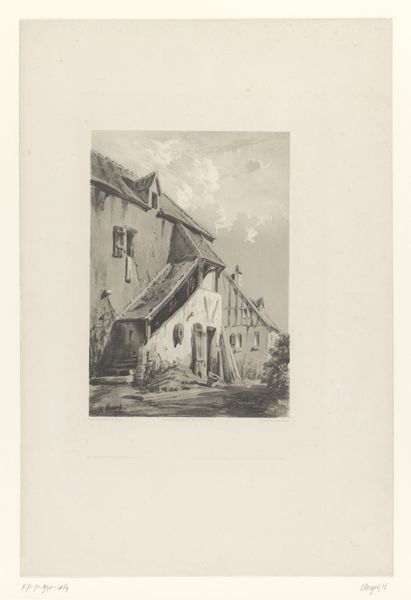

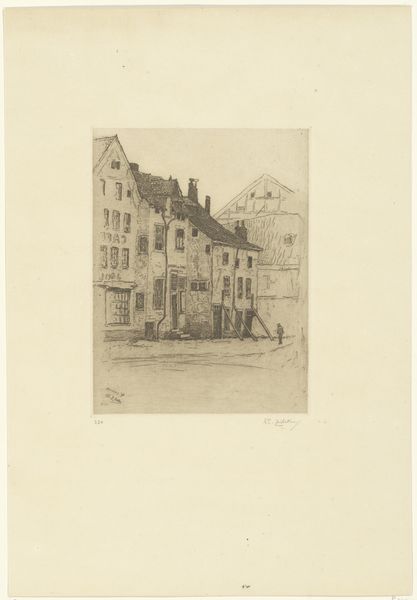

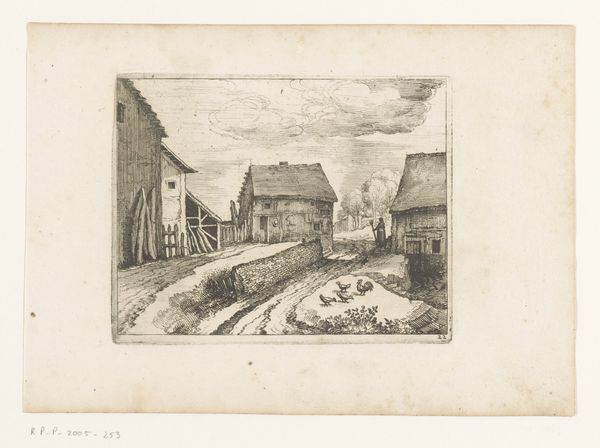

print, engraving

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 360 mm, width 547 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is Eugène Isabey's "View of fishing boats in a Breton town," created in 1832. It’s an engraving. It feels like it captures a really specific moment, like a snapshot of everyday life in this busy harbor town. What strikes you most about it? Curator: What I see here is not just a snapshot, but a coded depiction of labor and commerce. Consider the date – 1832. Europe was grappling with massive industrial shifts. The image romanticizes labor but think about who this image was made for. Was it for the people depicted? Unlikely. It was likely for the rising bourgeoisie, hungry for scenes of picturesque, supposedly simpler lives that masked the realities of the working class. Editor: That's interesting, I hadn’t thought about it that way. It's easy to get caught up in the detail and not consider who the intended audience might have been. But who do you think it affects how we understand its representation of labour? Curator: Precisely. The framing aestheticizes the labour; the "old engraving style" flattens lived realities into consumable imagery. It omits any harsh edges or suggestions of the grueling nature of maritime labor and trade at this time. It prompts a further question: Does this romantic view support the prevailing socio-economic structure? Editor: That's a powerful point. I see how the artistic choices – the level of detail, the almost postcard-like quality, distance us from the true experience of those workers. So, would you say this is a form of visual propaganda, in a way? Curator: I would say it offers a potent lens for examining the political undertones embedded within seemingly innocent depictions of daily life. Understanding art like this involves interrogating not just what’s visible but also what's been strategically obscured, who benefits from the obscuration and to ask questions about historical labor representation. Editor: Thanks, I see the picture in a very different way now! Curator: My pleasure. I feel like I better understand it too!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.