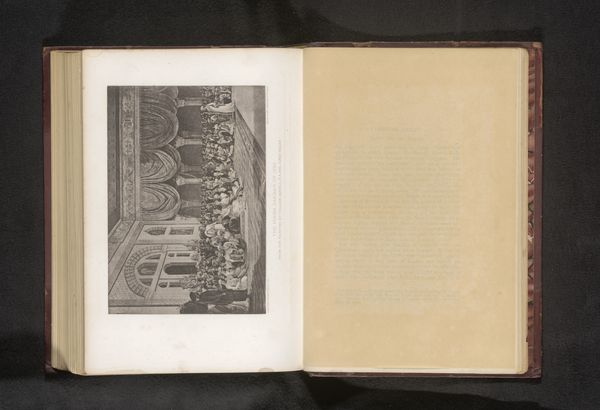

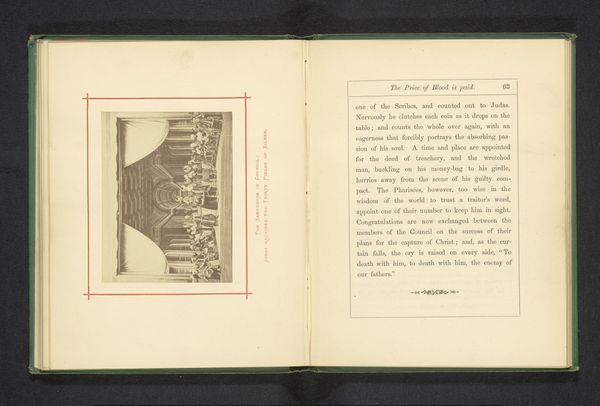

Fotoreproductie van een prent naar een fresco door Ghirlandaio van het banket van Herodes before 1863

0:00

0:00

print, etching, paper, photography

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

photography

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: height 92 mm, width 143 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a photographic print dating to before 1863. It's labelled "Fotoreproductie van een prent naar een fresco door Ghirlandaio van het banket van Herodes," and is attributed to Giacomo Brogi. What strikes you first? Editor: The semi-circular composition, it is unusual—immediately, I see the interplay of architectural forms and the contained narrative. The limited tonal range and crisp lines create a sense of depth. Curator: Considering Brogi’s other works, many of which depict architectural landmarks and urban scenes, I think he's less concerned with the inherent artistry, and more focused on documentation and reproduction, widening access to the great frescoes of the Italian Renaissance. Editor: I concede your point about accessibility, but that narrow framing and careful arrangement within it indicates more than simple documentation. Brogi makes deliberate choices about perspective, drawing the viewer's eye toward specific details of Ghirlandaio's original composition. Look how he captures that theatricality of Herod's feast. Curator: I am interested in what his studio workers were paid to create this. This print circulated at a time of burgeoning tourism, fulfilling the need for accessible souvenirs and reference material. Were the workers appropriately credited or fairly compensated? This wasn't simply a work of art, but an industrially produced object serving specific socio-economic needs. Editor: And that touches on an interesting point about reproduction. The very act of reproducing this work creates a dialogue across time. It asks questions about authenticity, aura, and the shifting experience of encountering art. Is this photograph more or less affecting than seeing the original fresco? Curator: Perhaps it doesn't have to be a binary choice. What is undeniable is the changing conditions of artistic production in the 19th century. Photography shifted the terrain, altering established hierarchies between artistic labor, reproducibility, and artistic creation. Editor: Indeed. It prompts us to consider how we value artistry itself. Close viewing yields appreciation of the complex arrangement of form that underscores meaning, just as you say focus on industrial elements underscores value in distribution and context. It's an aesthetic argument, certainly, but one deeply rooted in historical material.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.