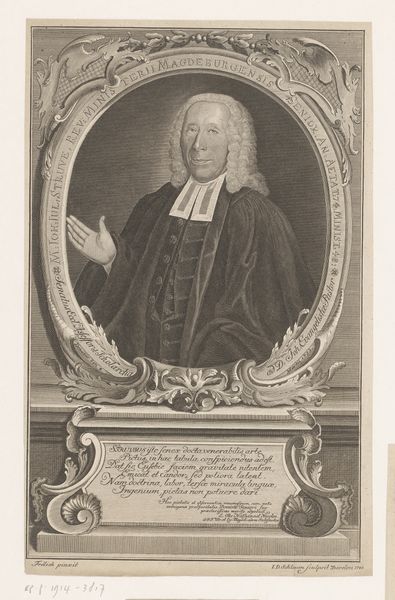

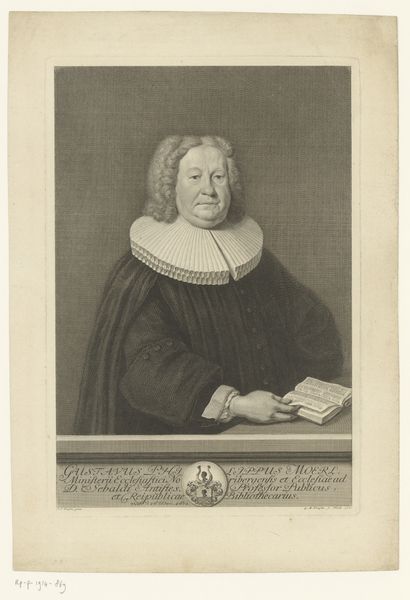

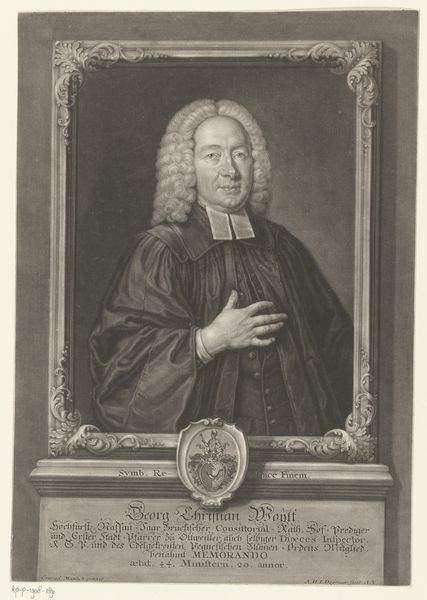

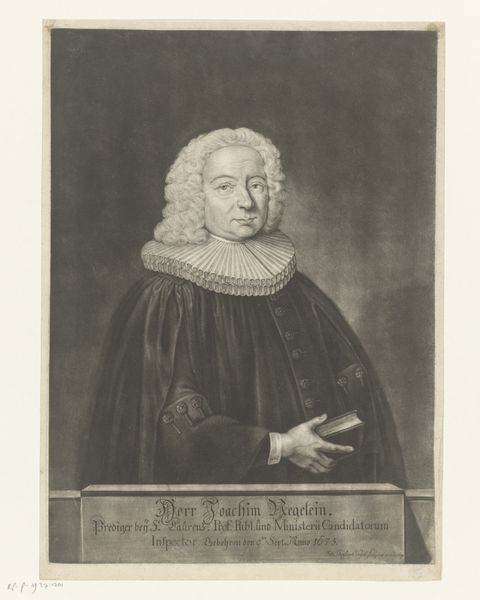

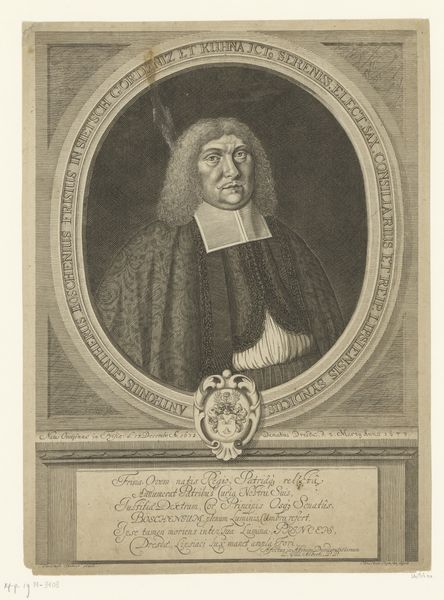

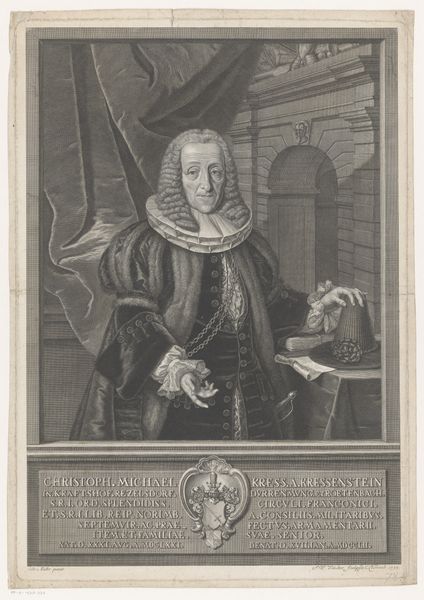

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 239 mm, width 160 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This print, dating back to 1749, is a portrait of Carl Ludwig, rendered with meticulous detail by Georg Lichtensteger. It resides here in the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: It's arresting. I'm struck by the high collar and his intense gaze, somehow both assertive and vulnerable. It makes me want to know more about who this person was in his specific time and place. Curator: Indeed. Let’s consider Carl Ludwig's position within the smaller council, the "kleinern Raths" in Nuremberg. Access to representation during the period would undoubtedly have meant access to wealth and influence. This engraving highlights how identity, even in portraiture, is tied to socioeconomic structures. Editor: That's evident in the formal trappings, the ruff, the patterned fabrics, but the most intriguing element for me is the object he’s holding. It's like some form of woven horn, almost like an abstracted cornucopia. I'm curious about what that symbolizes – fertility? Abundance? Connection to a specific trade, perhaps? Curator: You are correct, there may be an intentional connection to his social class and possibly wealth accumulation within the free imperial city, and the city’s self-fashioning, too. Let's not forget the implications for the broader understanding of baroque portraiture. He may not be nobility, but through printed reproduction of his image, there’s an undeniable attempt at self-mythologizing through iconography. Editor: Looking closer, the print itself conveys meaning. Its ability to disseminate images widely – to a different public sphere – is something often missing when examining the baroque, even in Dutch Golden Age painting. Curator: Yes. Printmaking granted agency. The layered textures achieved here, through hatching and engraving, elevate it above mere reproduction. This allows the artist, Lichtensteger, and Ludwig, his patron, to position themselves in society differently, too. Editor: It changes our reception and experience of seeing these portraits when considering where and for whom the image was meant to be circulated at the time of production. A printed object has an agency all its own! Curator: Absolutely, seeing how printed likeness operates to extend a kind of invitation to Ludwig's political networks offers interesting research for future visitors and students alike. Editor: For me, too, tracing symbols like the woven horn could open doors to understanding period-specific virtues and ideas around the cultivation of resources in this particular context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.