#

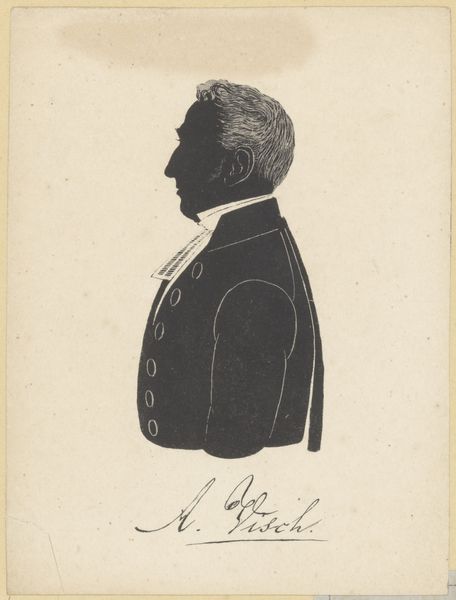

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

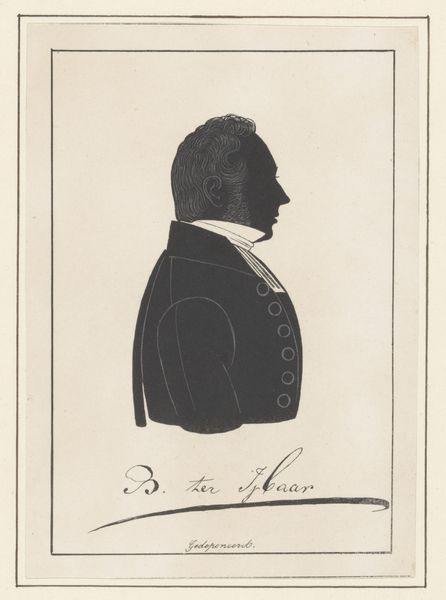

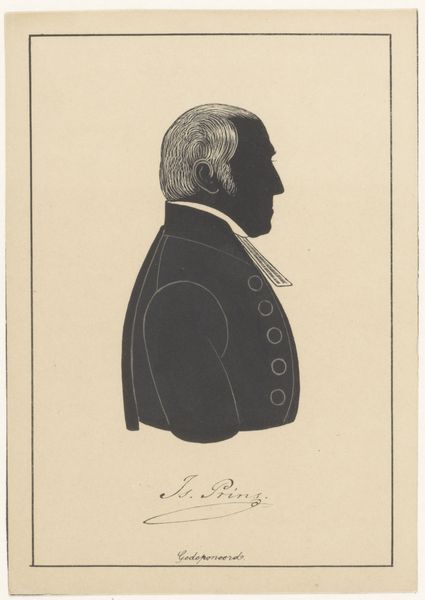

Dimensions: height 143 mm, width 106 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

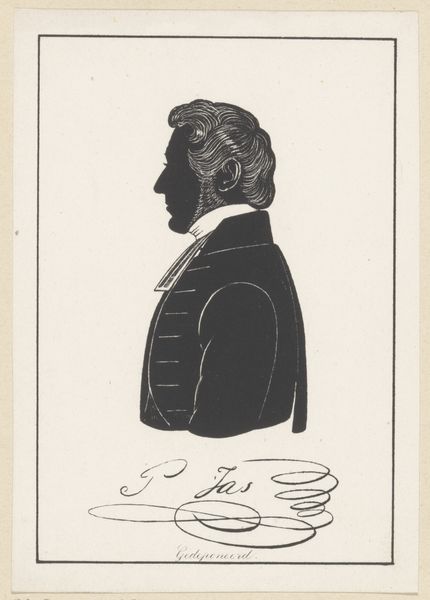

Curator: Welcome. We are looking at “Silhouetportret van Samuel Joannes de Hoest,” made sometime between 1809 and 1848. It's a print, housed here at the Rijksmuseum, created by Pieter (IV) Barbiers. What is your initial reading of this portrait, Editor? Editor: Stark. Stripped down, even. It’s like a shadow frozen on paper. All of the intricate details—or lack thereof—communicate a certain formality that is characteristic of portraits of that period, especially those portraying bourgeoisie males. It almost appears like a caricature of one. Curator: Indeed, the artist distills the sitter to the barest of graphic essentials. The pure black silhouette against the off-white ground emphasizes the clean lines of the profile. Consider how the contours, especially around the hair and collar, have such exquisite detail, achieved through skillful printmaking. Editor: Absolutely, the stark contrast forces us to confront what the portrait chooses to reveal and, perhaps more intriguingly, what it conceals. Given its historical period, was this portrait intended for private circulation, a way to subtly communicate social standing? A silhouette feels particularly telling; hiding as much as it shares. Curator: It resonates with the Neoclassical focus on simplification and ideal forms, but with a distinctly modern graphic sensibility. Think about the effect of mass reproduction—a portrait now democratized, readily disseminated, and yet still proclaiming the subject's identity. Editor: Precisely. The “democratization” you speak of is exactly where its historical context comes into play. Who had access to these prints, how did the subject perceive it, and what visual power does it wield at this period, as both status symbol and intimate marker of the self. What does the very act of making a silhouette portrait—a cutting away, a simplification—communicate about power and identity in early 19th-century Netherlands? Curator: It’s a compelling thought – and reminds us how even seemingly straightforward portraits can carry complex dialogues about representation. Editor: Exactly. The lack of color amplifies these conceptual layers. A portrait of negative space opens more doors than it closes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.