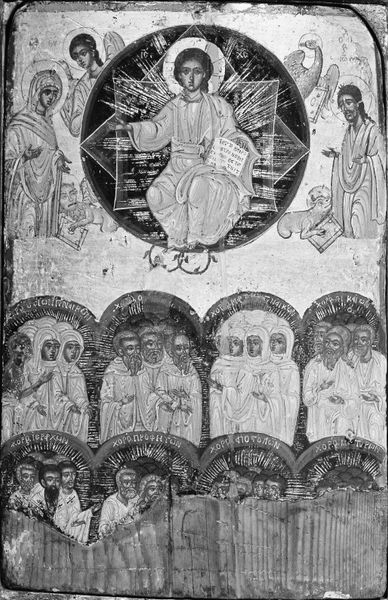

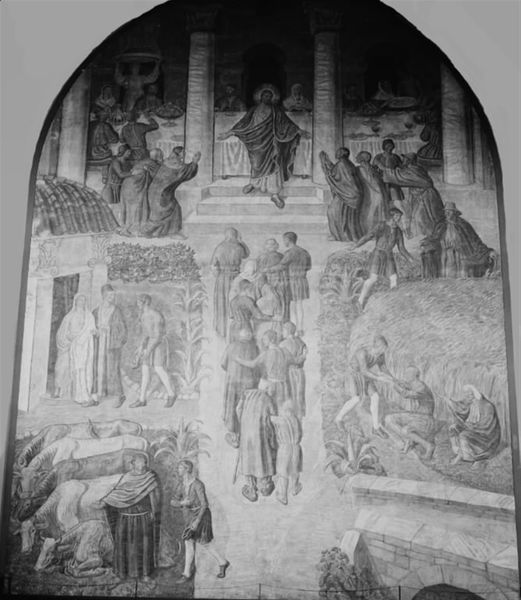

tempera, mural

#

portrait

#

byzantine-art

#

medieval

#

tempera

#

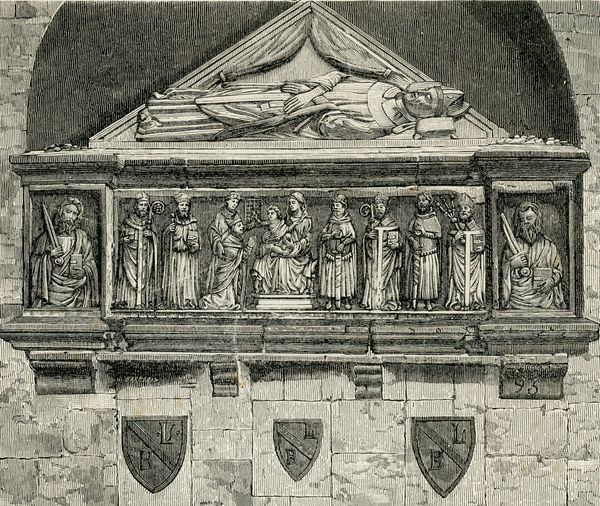

sculpture

#

figuration

#

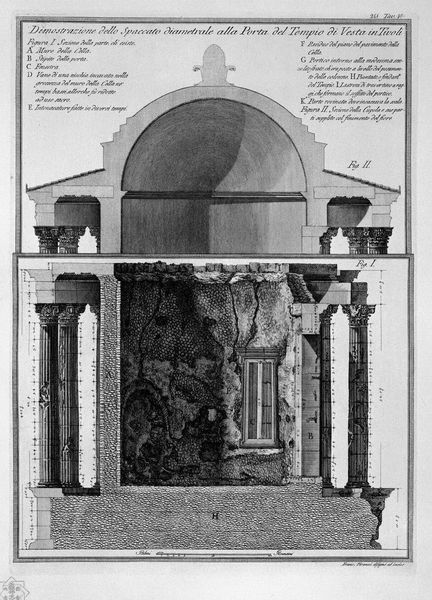

geometric

#

history-painting

#

mural

#

statue

Copyright: Public domain

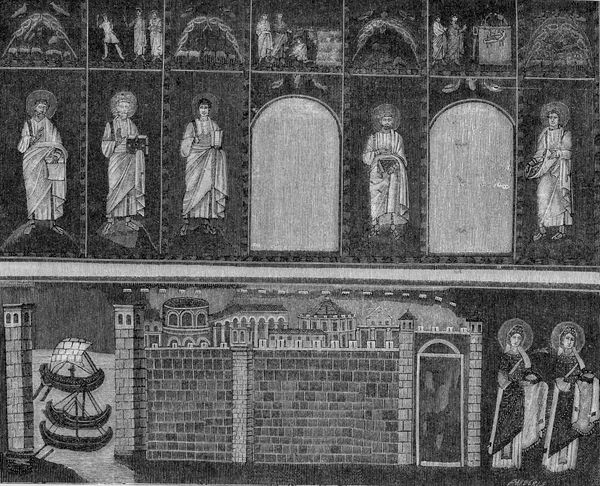

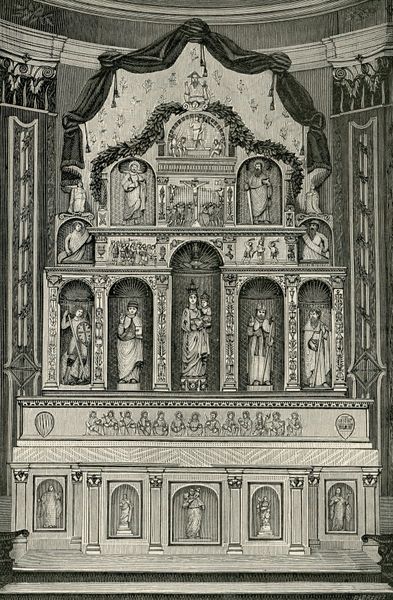

Curator: Interesting that Barberis titles this "Fatti Della Vita Di Gesù Cristo, Varii Profeti E Martiri", circa 1900. This looks like it was done with tempera, probably a mural too, which feels incredibly labor intensive. It feels very static, doesn't it? Editor: It does! So much symmetry. What strikes you the most about this Byzantine-style work? Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the material processes at play here. Consider the socio-economic conditions that would support the creation of a work like this. Tempera requires pigment, binder, and support. Each of these elements would have been sourced, likely at great expense of time and capital. Think about the artist laboring in relative obscurity, reproducing an ancient, likely religious, narrative. Do you think Barberis considered the weight of that legacy? Editor: I wonder if he felt more like a craftsman, replicating tradition? Did he feel separate from the 'high art' world? Curator: Precisely! Where does craft end and art begin? A question made particularly sharp by pieces like this one that draws inspiration and materials from an artistic tradition with firm beliefs on labor and materials. Also, observe the stylistic flattening that evokes Byzantine mosaics but is achieved with very different techniques, potentially responding to different market constraints. Were they perhaps intended for different consumers and different locations, as well? Editor: So, it’s not just about the religious subject, but also the conditions that allowed its creation and how those conditions have changed between the Byzantine era and 1900? It changes my perspective to consider labor and economics in this "religious" context. Curator: Exactly! By exploring its production and consumption, we expose the complex dialogue between Barberis, his materials, and the expectations of his society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.