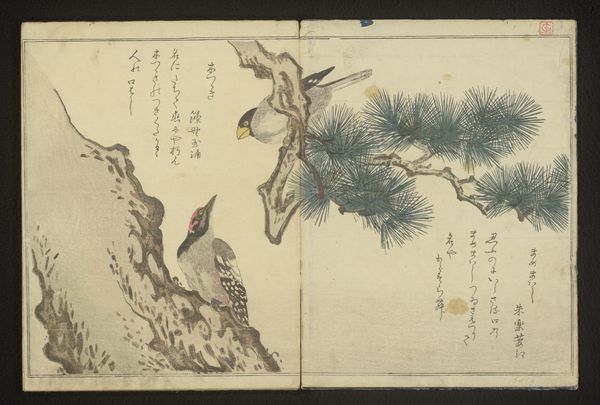

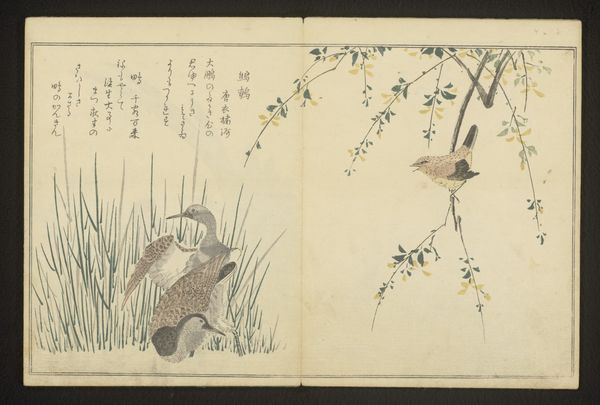

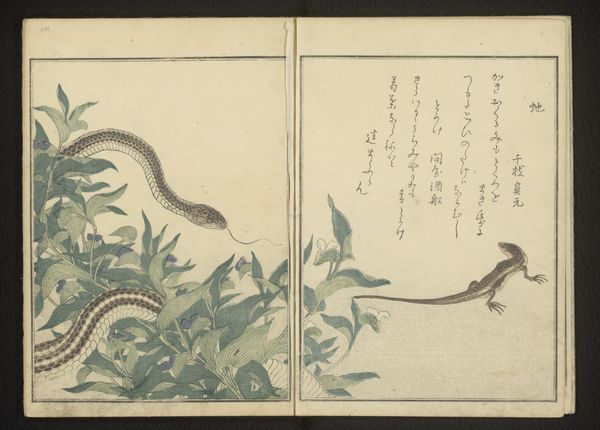

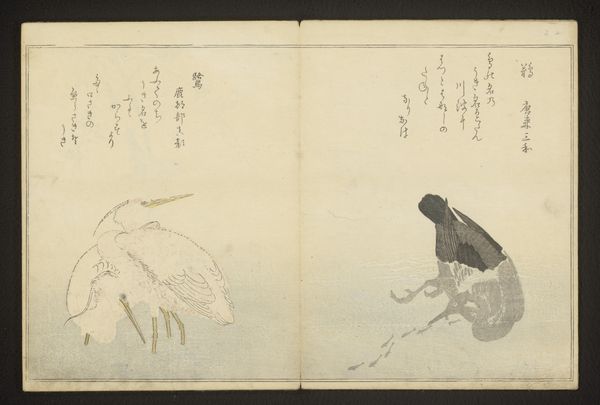

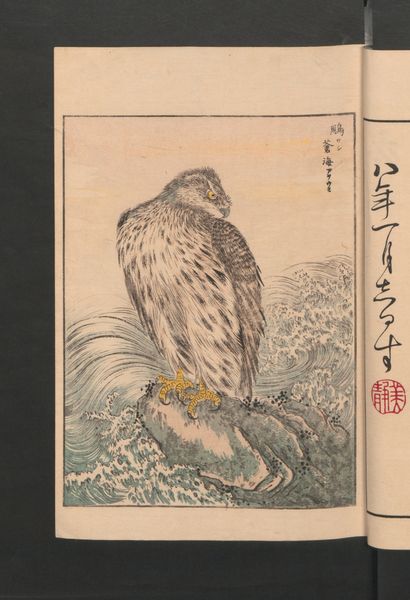

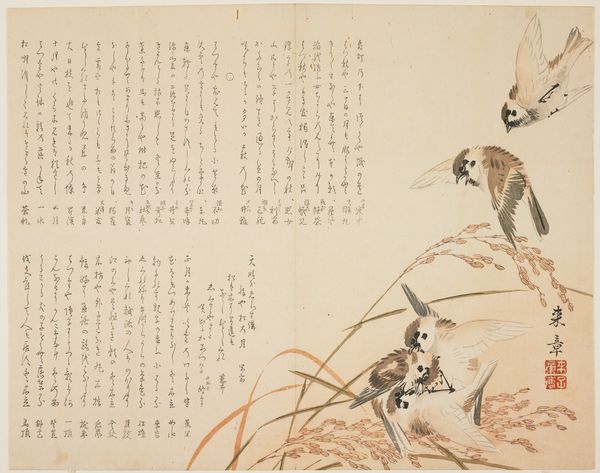

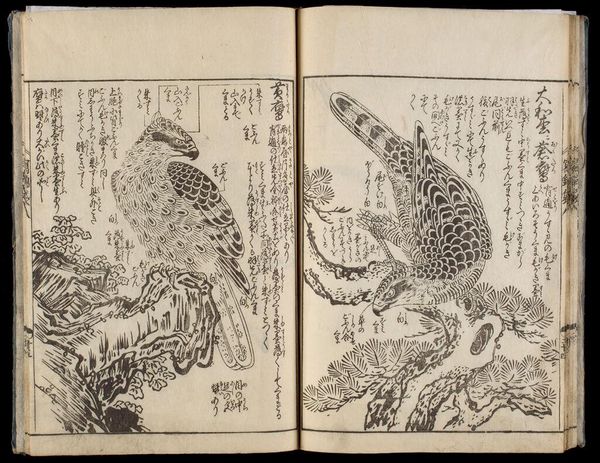

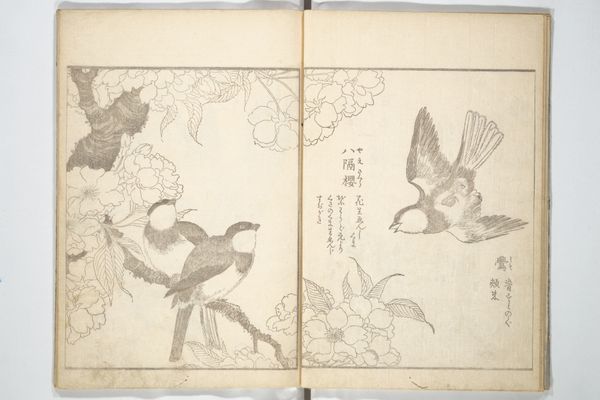

print, woodblock-print

#

aged paper

#

pen drawing

# print

#

pen sketch

#

asian-art

#

sketch book

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

woodblock-print

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen and pencil

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 251 mm, width 187 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This lovely two-page spread is "Quail and Skylark," a woodblock print from around 1796 by Kitagawa Utamaro, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. The scene has such a delicate feel to it; almost like a page from a treasured book of natural history. What are your thoughts on this work? Curator: It’s interesting to see this piece in light of the Edo period's strict social hierarchy. Utamaro, a leading Ukiyo-e artist, often depicted courtesans and actors – figures from the pleasure districts who were technically outside the formal social structure. Editor: So, a seemingly simple nature scene… as social commentary? Curator: Perhaps. The choice of depicting "lowly" animals – these aren't symbols of wealth or power – could be a subtle reflection on the societal constraints of the time. How was the natural world perceived by those living in the rapidly growing cities of Japan at the end of the 18th Century? What did "nature" signify, compared to a strictly controlled society? Editor: I hadn't considered that angle at all. I was focused on the graceful lines and composition. Curator: And the print technique is significant. Woodblock printing made art more accessible to the common people. Ukiyo-e prints weren’t just aesthetically pleasing, they were a form of popular culture, reflecting and shaping public tastes and ideas. Who was the audience for prints like these, and what role did they play in circulating ideas in Japanese society at that time? Editor: So this artwork isn’t just a pretty picture, it's embedded within complex social dynamics. I definitely have a better understanding now. Curator: Indeed. Art rarely exists in a vacuum; examining its historical and cultural context often reveals fascinating layers of meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.