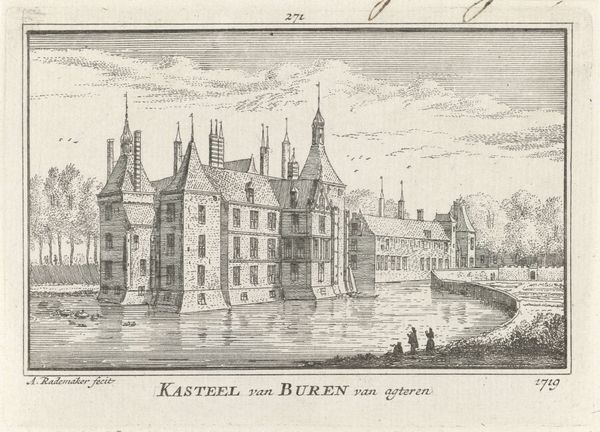

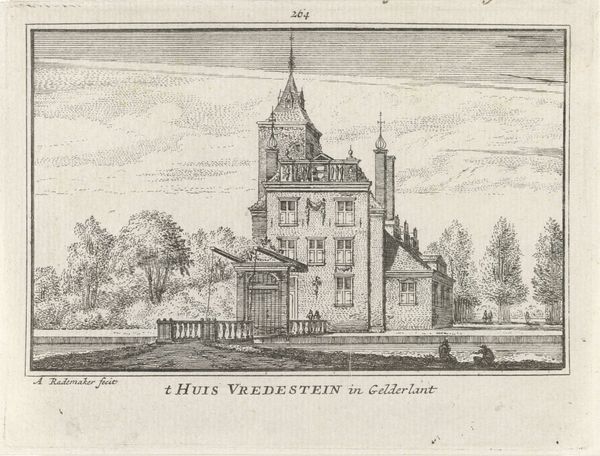

drawing, etching, paper, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Abraham Rademaker's "Gezicht op Kasteel Batestein, 1645," a work likely created between 1727 and 1733. This drawing combines etching and engraving on paper, depicting a rather stoic view of the castle. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It strikes me as somewhat melancholy. The stark lines and muted tones create a feeling of distance, a bygone era. The landscape almost dwarfs the people within it, emphasizing a sense of isolation. Curator: That melancholic atmosphere is certainly present. Rademaker's historical context plays a key role; these kinds of landscape depictions became increasingly popular as a means to document and, in a way, idealize the Dutch countryside and its historical monuments. Editor: Absolutely, and I think that ties into something deeper about collective memory. The choice to portray the castle evokes notions of power and authority, particularly during the Dutch Golden Age, though through our contemporary understanding, it’s impossible not to see that it overlooks who this power served and who it systematically excluded. Curator: Interesting point. Considering the etching and engraving techniques used, this allowed for wider distribution and accessibility of these images. Think of them as early forms of public relations, projecting images of strength and national pride. Editor: It is all carefully curated, down to the small figures strategically placed to guide the eye. But who controlled that narrative? Whose stories were elevated while others were buried, whose labor allowed that idyllic scene to even be imagined? Those absences become telling. Curator: The landscape tradition in Dutch art frequently sidesteps those direct socio-political commentaries, but to your point, we must consider whose story gets told, and, crucially, who gets to tell it, both then and in how we engage with it now. Editor: Precisely. By engaging with art history through the lens of contemporary critical theory, we invite viewers to explore beyond what’s represented to examine the complexities of historical narrative. Curator: This piece serves as a poignant reminder that history isn't simply what's presented; it's also about what's been deliberately, or unconsciously, left out of the frame. Editor: I agree. And art becomes a powerful invitation to begin addressing such imbalances, recognizing art's public role and imagery in our own socio-political landscape.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.