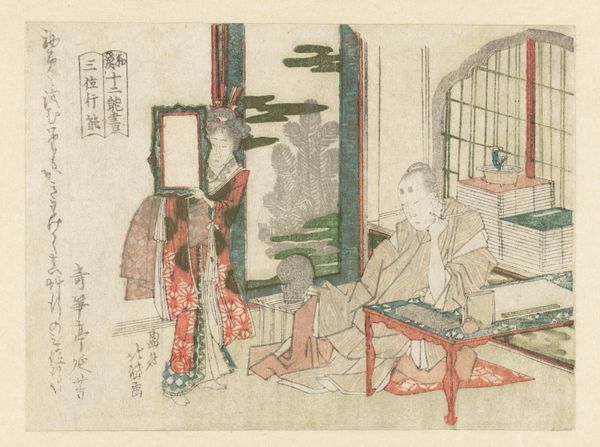

Zhuangzi (Japanese: Soshi), from the series "Shunshoku ressenkyo" c. 1801 - 1818

0:00

0:00

#

portrait

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

Dimensions: 14.8 × 19.5 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Teisai Hokuba's print, "Zhuangzi from the series 'Shunshoku ressenkyo,'" created sometime between 1801 and 1818. There's an intimate feel to the piece, almost like we're intruding on a private moment. What strikes you when you look at it? Curator: Immediately, the question of viewership comes to mind. Ukiyo-e prints, especially those depicting women in domestic settings, were often produced and consumed within specific social strata. The depiction of leisure and refinement, even in this seemingly "private" setting, signals certain societal values and class aspirations. Does the woman's placement mirror the man's? Editor: Good point. She's partially obscuring him. What do you make of their relative positions within the frame? Is she rejecting him, is she an aide, a distraction from the reading, or perhaps representative of other types of commentary in the political world. Curator: Her apparent distraction, contrasted with the scholarly pursuit of the male figure, taps into established gender roles. Prints like these, distributed widely, reinforced or challenged these social norms, sparking conversation about what it meant to be a learned man or woman in Japanese society. Who were the buyers of this print? That shapes interpretation. The imagery serves specific purpose within that society. Editor: That's fascinating! I never considered how the circulation of these images played such a crucial role in shaping social dialogues around gender and class. The narrative shifts dramatically knowing the social context. Thank you for bringing that point. Curator: Precisely! That interplay between artistic representation and societal reception is key to understanding art history. By focusing on social status within art it makes history even more vivid.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.