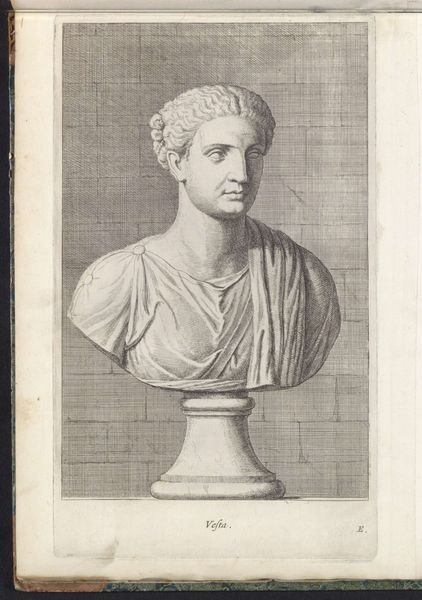

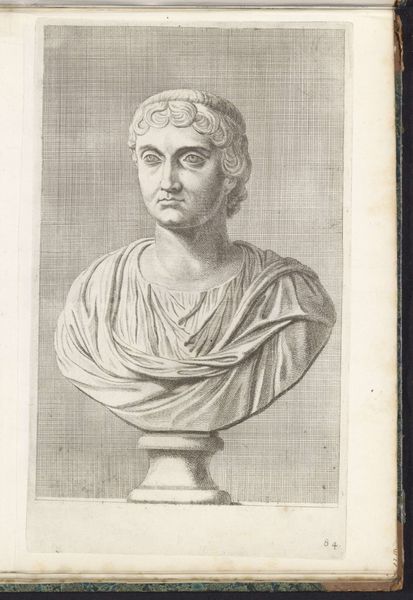

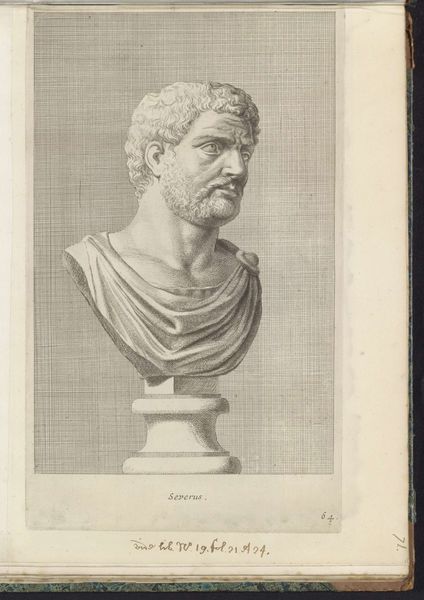

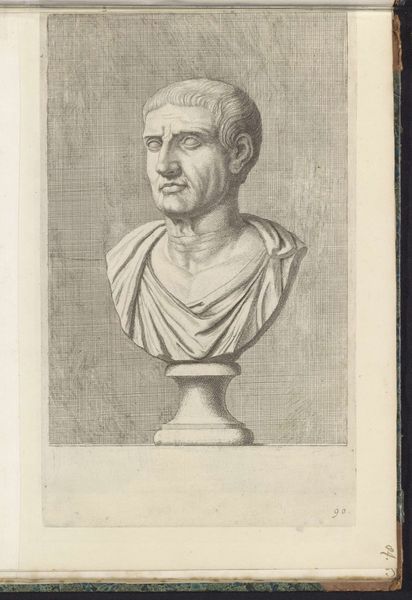

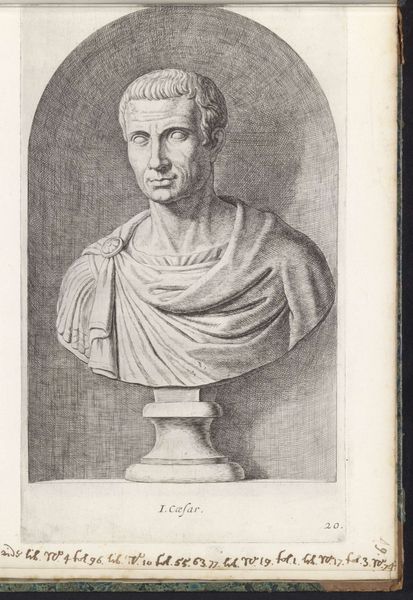

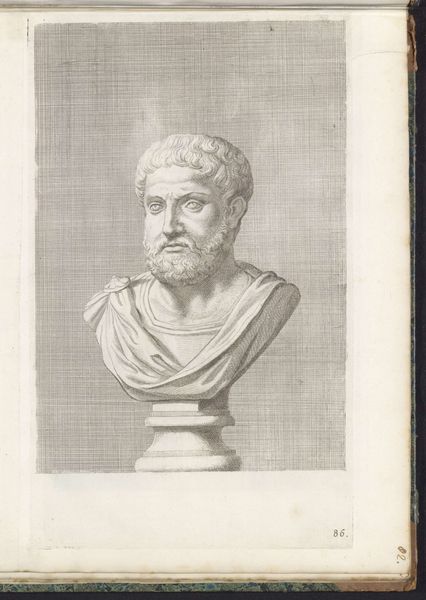

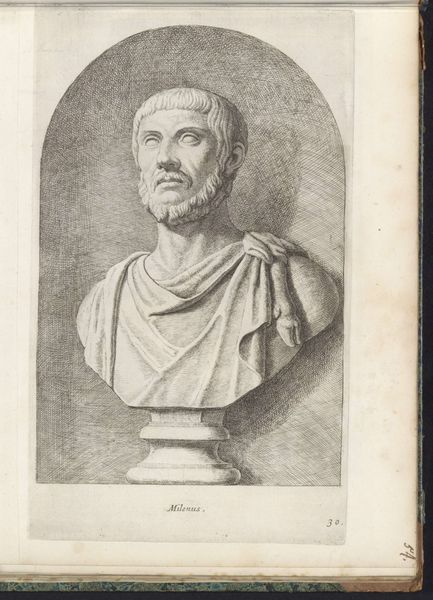

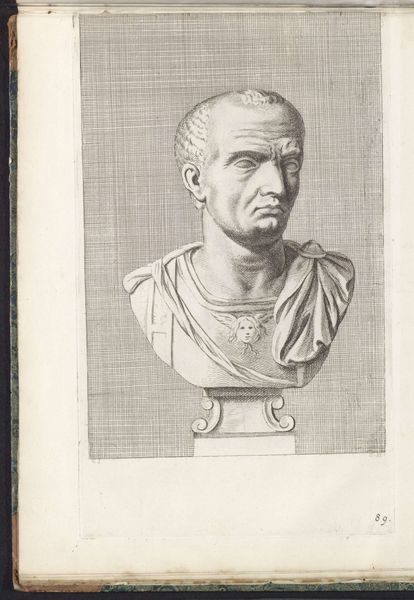

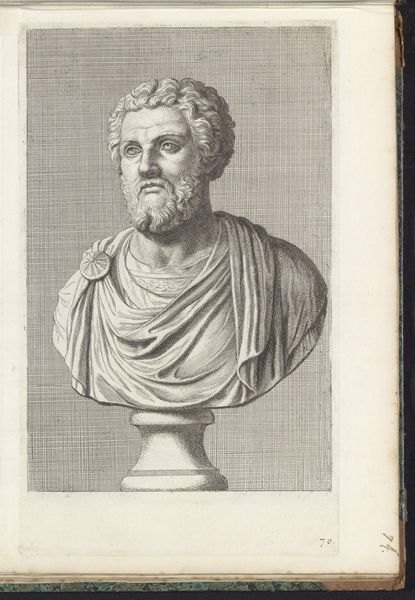

print, marble, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

classical-realism

#

history-painting

#

marble

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 325 mm, width 195 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

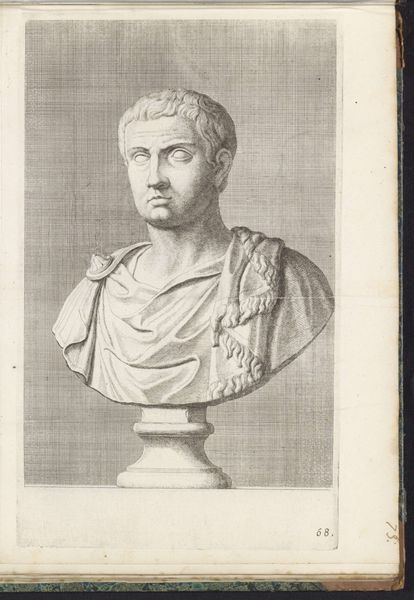

Curator: Standing before us is an engraving titled "Buste van keizer Commodus," dating back to between 1646 and 1670. Editor: There’s a somber mood to it. It’s stark, rendered in a style that really captures the texture, but in a contained way, like a precise architectural rendering. Curator: The artist, Hubert Quellinus, provides us with a window into the past, not just of Commodus himself, but of how the Dutch Golden Age grappled with portraying power. The choice of engraving reflects the era’s burgeoning print culture, a key medium for disseminating ideas and images. The historical and political contexts surrounding Commodus's reign invite reflection upon power dynamics throughout the ages and their complex manifestations. Editor: I find myself immediately thinking about the physical process. Imagine the skill required to transfer the three-dimensionality of marble into a two-dimensional print with such meticulous crosshatching. And it has me wondering about accessibility. Was it intended as a study, a decorative object, or a means to democratize the image of a powerful figure, making him accessible to a broader audience through a relatively reproducible medium? The material choice speaks to broader issues of art production and dissemination in 17th-century Netherlands. Curator: Absolutely. The act of replicating a marble bust—itself a statement of Roman imperial power—via engraving for mass consumption creates layers of meaning. How does the transformation in material and scale alter Commodus’s authority and intended message, both in its own time and the moment Hubert Quellinus produced this print? How can one connect this depiction with feminist theory when so few of these grand depictions of power represent the experiences and status of woman? Editor: And thinking about materials again, why choose engraving to reproduce this classical bust? How might different printmaking processes, or different material selections, change the impression that this engraving offers its viewers? There were numerous possibilities in print media production available. Curator: These inquiries unlock conversations regarding the dynamics of labor, distribution, and cultural value surrounding image-making within Dutch society, extending towards contemporary discussions regarding cultural appropriation and its reverberations. Editor: Yes, seeing it through the lens of process reveals how this reproduction wasn’t just about aesthetics, but about power and control over how images were created and consumed. I feel much more knowledgeable now than before. Curator: Indeed!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.