photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

contemporary

#

black and white photography

#

social-realism

#

photography

#

black and white

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

ashcan-school

#

realism

Dimensions: image: 80.01 × 80.01 cm (31 1/2 × 31 1/2 in.) sheet: 108.59 × 101.6 cm (42 3/4 × 40 in.)

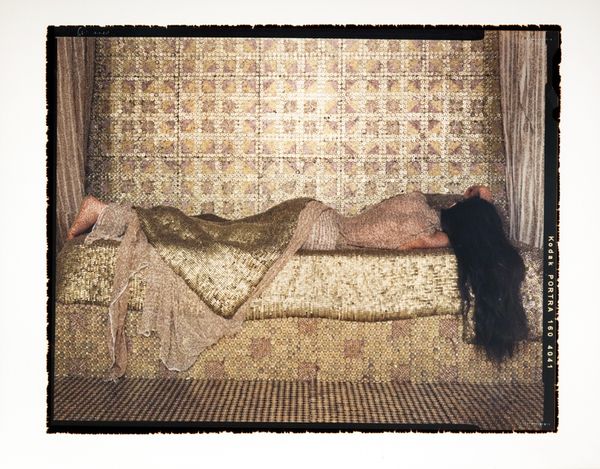

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

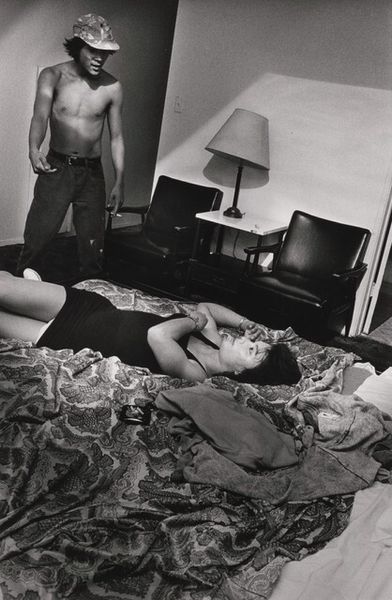

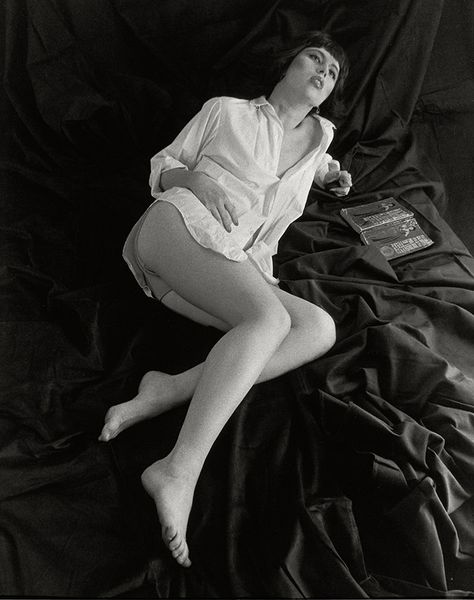

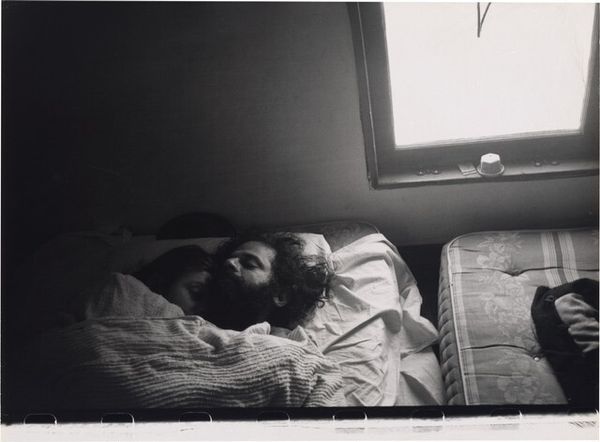

Curator: Let's turn our attention to Rosalind Solomon’s piece titled "New York" from 1987. Solomon is known for her poignant black and white portraits, often diving into complex social issues. She presents here a gelatin silver print—quite stark, isn't it? Editor: Yes, stark is definitely the word that comes to mind. It has an immediate impact, bordering on unsettling. The high contrast emphasizes the vulnerability of the subject and the palpable disarray of the room, giving it almost a social realist aesthetic. Curator: Indeed. This portrait is compelling as a document of its era. Consider New York in the 1980s—a city grappling with the AIDS crisis, socio-economic disparities. Solomon doesn’t shy away from showing the realities of that period. Editor: Exactly. The newspapers strewn on the floor hint at the wider social narrative. The man’s thin frame, his gaunt face, these details evoke the AIDS epidemic without explicitly stating it. It asks the viewer to engage with a story of loss and systemic failure. Curator: It is a far cry from the glamorized portrayals of New York we often see. What I find interesting is the tension between the individual and the institutional. Solomon invites us to question the forces that shape individual experience and well-being within urban structures. Editor: I think this tension speaks to the way power operates, especially along the lines of race and class. There is also gender here, since there are expectations about care-giving, as well as different cultural expectations on men's expression of disease or grief. How do institutions shape what is captured, valued, and remembered, and how do people fall through the cracks? Curator: A vital question. This is where Solomon's work functions as an important piece of visual culture, reflecting the power dynamics that often remain unacknowledged. It urges a consideration of marginalized stories within dominant historical narratives. Editor: Precisely. It moves beyond just documenting reality—it prompts us to question whose realities get documented and why. Thanks for opening my eyes to its history. Curator: And thank you for bringing it into the present, encouraging new narratives around it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.