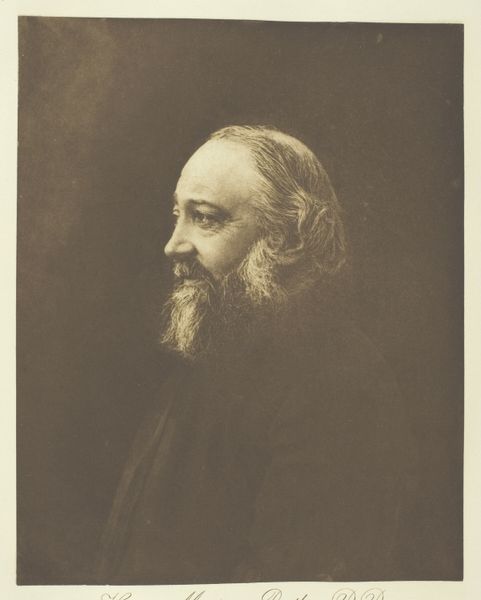

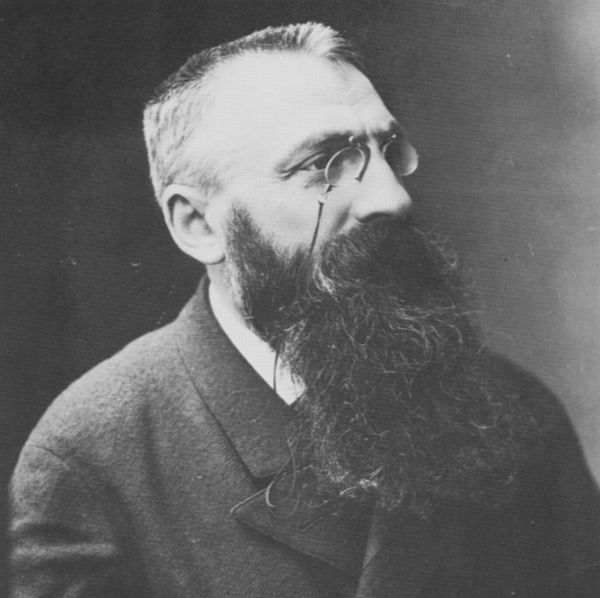

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

portrait

#

photography

#

black and white

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

modernism

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

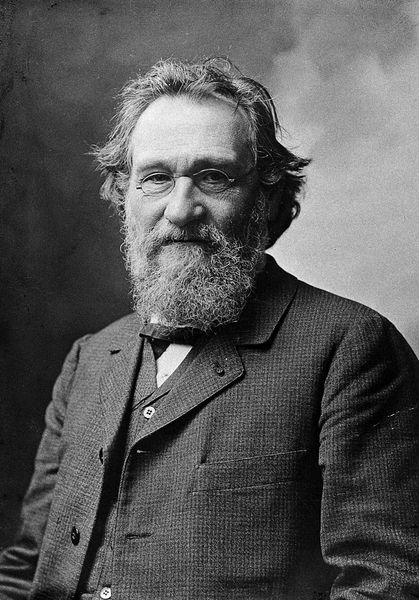

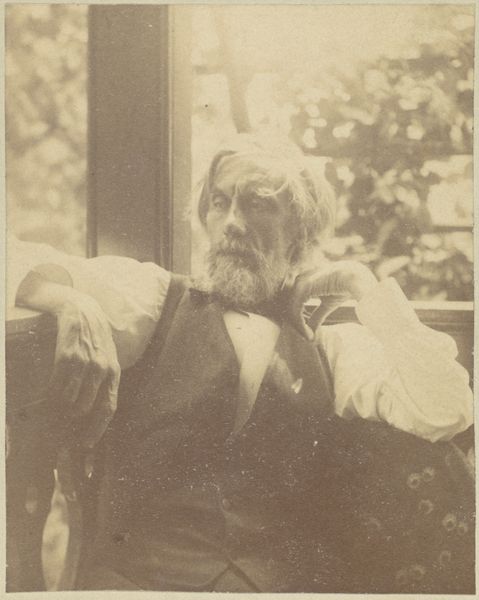

Curator: Immediately, this image feels like a study in purpose. The sitter looks directly at the camera, a pen in hand, as if interrupted from profound thought. Editor: And what exactly are we looking at here? Give us some context. Curator: This gelatin silver print is a portrait of Ilja Metschnikow, taken by Felix Nadar. Though undated, it speaks to Nadar's modernist sensibilities in portraiture. Editor: Metschnikow, of course, was a significant figure in microbiology. Nadar captured so many figures prominent in the development of science. But the real power here, for me, is in how Nadar uses photography to convey social standing. This isn't just a record, it is an exercise in myth-making. Curator: Precisely. Note how Nadar uses the visual language of realism—the clear, direct gaze, the sharp detail—to create a sense of authentic encounter with the man. It's about imbuing the photograph with an aura, reinforcing Metschnikow's intellectual weight. The dark tones lend it gravitas. Editor: Although there is no indication of setting other than a vague wall in the background, he looks powerful and serious in a way that only these early photos are able to show. It's that strange, still gravitas of having to hold so still, giving him the time to seem more serious than most people really are. It also reflects how scientists wanted to be seen in those years—determined and dignified. It says much about how we began to depict important public figures, shifting toward something a bit more solemn and staged. Curator: That brings up a powerful point: portraiture became increasingly crucial as a medium for solidifying cultural memory and legacy. A scientist or a politician would employ all the available means, from realism to lighting effects, to project specific images of intellectual capacity, seriousness, and trustworthiness. Consider the symbolic charge invested in Metschnikow's focused attention and hand, paused with pen over paper. It reads to me as his labor, thought, and scientific advancement. Editor: This certainly pushes us to consider not just who Nadar photographed, but why and how. He wasn't merely capturing faces, but actively shaping how an entire era perceived its intellectual elite. It's fascinating to consider how these historical figures used photography to promote particular personal and professional identities, solidifying their place in society. Curator: I find myself lingering on Nadar’s capacity to bring forward the psychological intensity of the sitter through subtle gestures, like that slight furrowing of the brow. It lends humanity and vulnerability to the more rigid expectations of his professional standing. Editor: Absolutely. Seeing it through that lens, Nadar has shaped much of how we still recognize authority figures today, even generations removed from these early portrait techniques. It's the power of staged sincerity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.