Copyright: Public domain

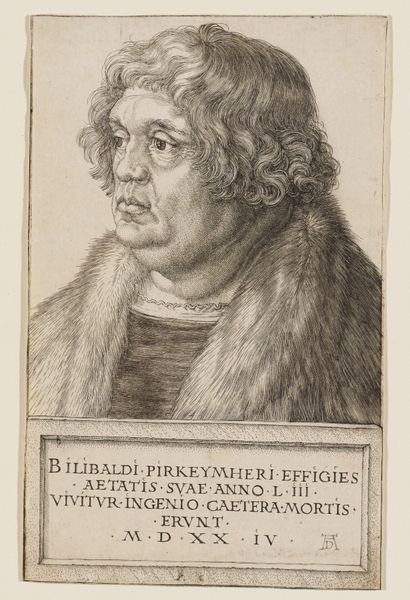

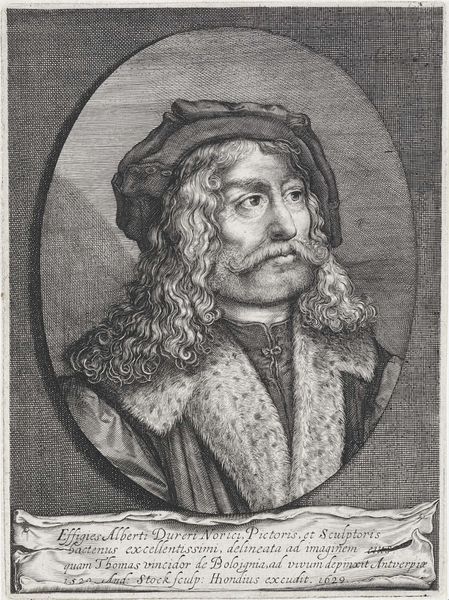

Editor: Here we have Albrecht Dürer’s "Willibald Pirckheimer," a drawing from 1524. It strikes me how realistic and unidealized it is for a portrait of the time; almost blunt in its portrayal. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Well, the "bluntness" you mention is precisely what makes this portrait so interesting historically. Pirckheimer was not just any sitter; he was a prominent humanist, a man of intellect. Dürer’s choice to depict him so frankly—the lines of age, the fullness of his figure—speaks volumes about the changing role of the portrait in Renaissance society. What do you make of the Latin inscription? Editor: I see it now. "He lives through his genius; all else is mortal.” It emphasizes Pirckheimer’s intellectual contributions, right? As if the portrait’s purpose isn’t mere flattery. Curator: Exactly! It elevates him based on his mind, his writings, his humanist values. Dürer and Pirckheimer were part of a network of intellectuals reshaping societal values through their art and writing. Think of the printing press – How did printed portraits democratize access to these intellectual figures and their ideals? Editor: I hadn't thought of the implications for wider audiences! Suddenly, intellectualism wasn't just for the elite anymore, but Dürer played a pivotal role. Curator: Precisely. Dürer used his art to promote specific ideals. What initially struck you as “blunt” becomes a conscious artistic and social statement about Pirckheimer's legacy and, in turn, Dürer’s contribution. Editor: This has shifted my perspective on Renaissance portraiture and patronage so much. Now it feels less about aesthetics and more about advocating ideas. Curator: Indeed, and that's where the true richness of historical art lies: in uncovering those layers of intention and cultural influence.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.