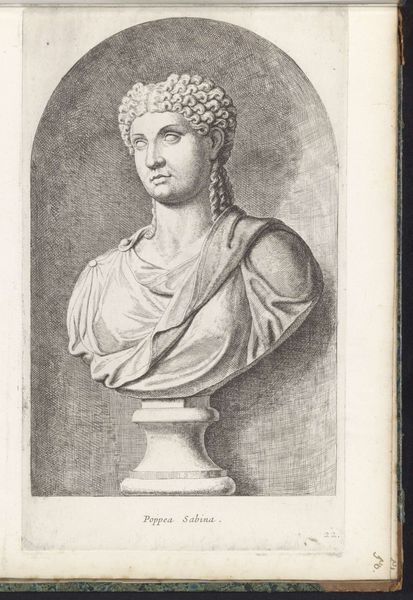

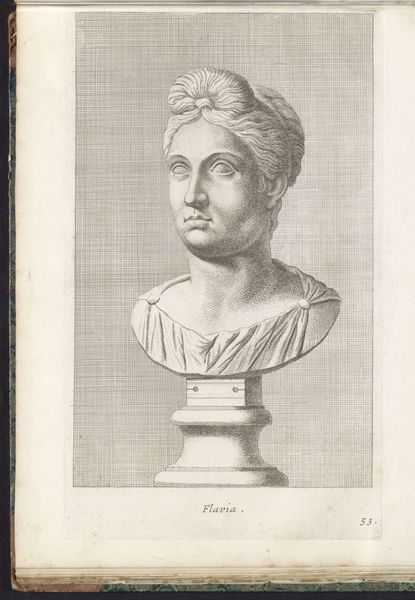

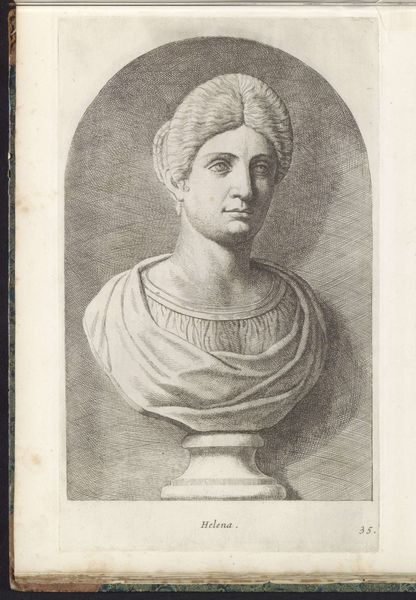

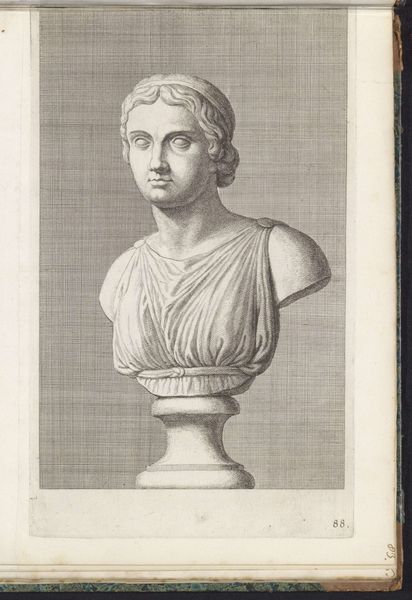

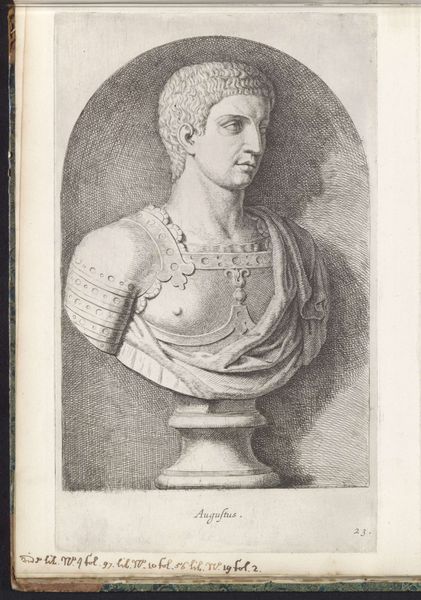

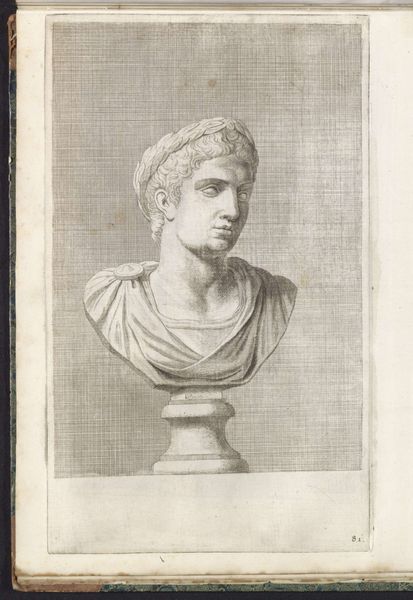

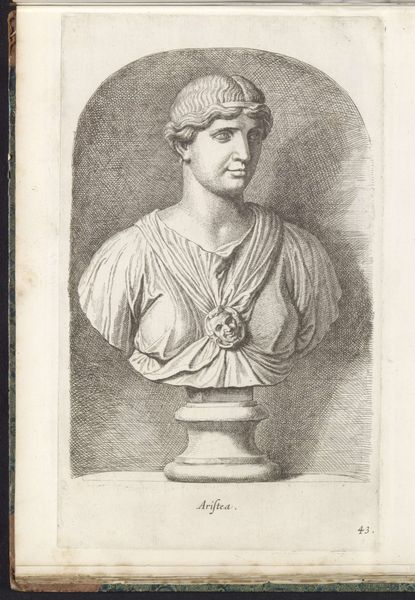

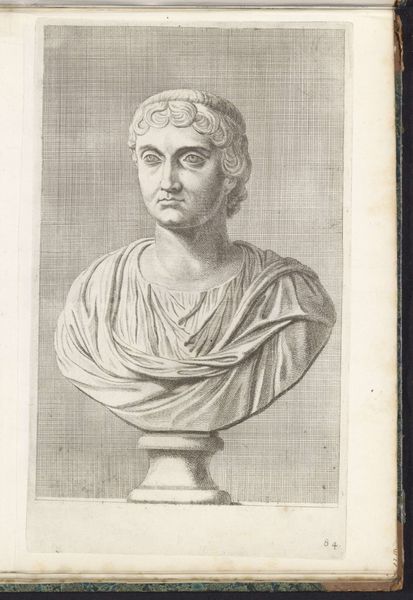

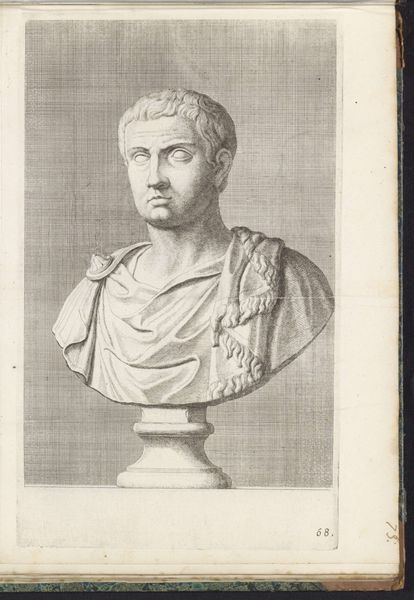

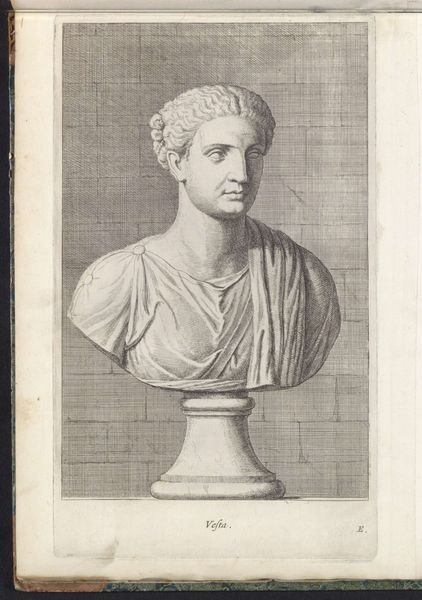

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

form

#

romanesque

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 325 mm, width 194 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Hubert Quellinus’ “Bust of Emperor Gordianus III,” an engraving dating back to the mid-17th century, sometime between 1646 and 1670. It's quite the piece of classicized realism. Editor: It strikes me as almost ethereal. The precise lines of the engraving give it this delicate, otherworldly feel. He almost doesn't seem entirely present. Curator: It’s interesting you say that. Printmaking during this period, especially engraving, had a crucial role in disseminating knowledge. Reproductions like this made antique sculpture accessible to a wider audience beyond the elite who could visit Rome, helping shape Neoclassical tastes and influencing political symbolism. Editor: So it’s less about the individual Gordianus and more about the *idea* of empire? The reproduction removes the tactile element of sculpture, turning him into pure concept? Curator: Exactly. Quellinus, though a Flemish artist, engaged with a very specific classical visual language. Note how Gordianus’s likeness, while aiming for realistic features, also adheres to established ideals of Roman portraiture. This connects him to a lineage of power, lending legitimacy and authority to his image. Editor: And the Medusa on his breastplate? Was Gordianus III particularly known for… turning people to stone? Curator: (Laughing) Not in the historical accounts! Medusa was a common symbol in Roman military iconography representing protection and strength. Her fearsome visage was intended to ward off enemies and inspire courage. Placing it on his armor emphasizes Gordianus's role as a military leader. Editor: I love that contradiction – the refined fragility of the print meeting the brutal power symbols. I also imagine owning such a portrait provided some clout; after all, a fellow of importance and education, and with taste. Curator: Undoubtedly! These prints circulated among collectors, artists, and scholars. They fostered dialogues about art, history, and empire. By examining them, we gain insights into the power of images and how they actively shaped perceptions of the past in early modern Europe. Editor: The ghost of an emperor whispering across centuries of political machinations. I find it truly captivating. Curator: Indeed. It’s a powerful testament to how art serves not only as a reflection, but also as an active participant in history's unfolding narrative.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.