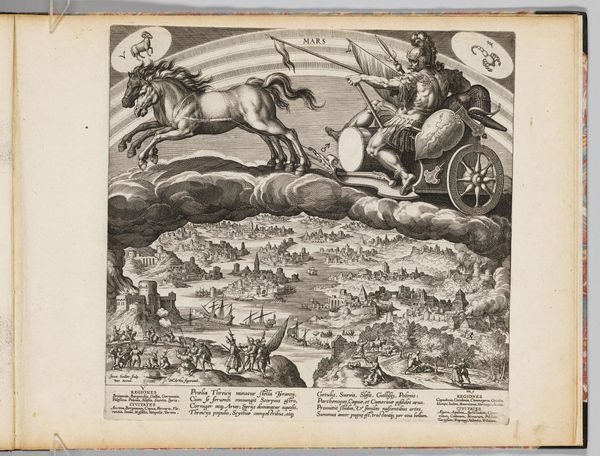

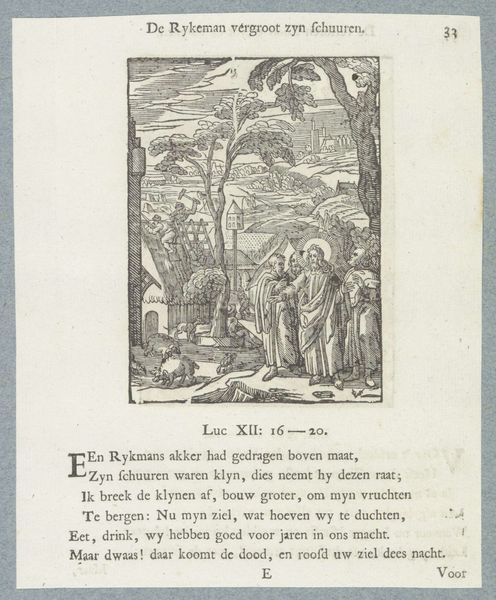

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 242 mm, width 247 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

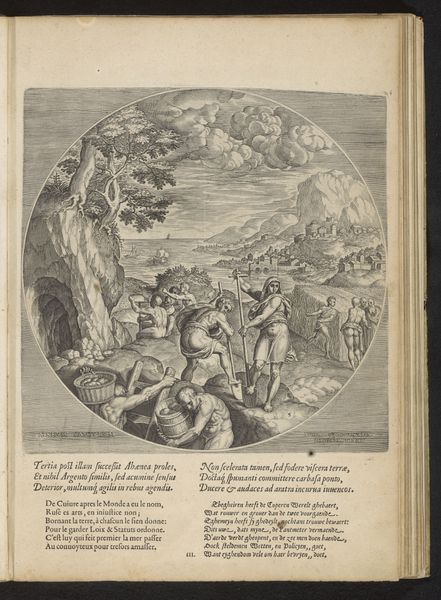

Curator: This is "Zilveren Eeuw," or "Silver Age," an engraving made in 1573 by Philips Galle. It resides at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial reaction is one of coolness, almost detachment. The landscape feels very formal and the figures seem posed, without true emotion. There’s a distinct lack of warmth despite the implied scene of agriculture and community. Curator: Galle's piece depicts the Silver Age from classical mythology, following Hesiod’s account of humanity's decline after the Golden Age. It visualizes a shift in human existence—a life less idyllic and more dependent on labor. The imagery reflects humanity moving from a state of ease to one of work and need. Notice the circular frame; it gives a sense of completion, but maybe also limitation. Editor: That circular form immediately struck me too. Structurally, it forces your eye to follow the scene almost as if watching a play, but that framing combined with the pale values make it seem as if viewing history under glass—clinical, preserved. Look at how Galle uses fine, cross-hatched lines; it defines shapes clearly but creates a stark, almost graphic feel. Curator: Exactly. The shift from divine ease to human toil is shown symbolically. We see people building shelter, tilling the land—symbols of hard work and self-reliance replacing nature's bounty. There is Jupiter mentioned here, marking an epoch after which shelter and agriculture emerge as necessities of the feminine nature of nurture. Editor: Semiotically, the ox pulling the plow communicates this change starkly, a forced domestication and taming of nature mirroring the shift in human temperament from simplicity to resourcefulness to labor. Curator: And the landscape itself supports that. The rugged terrain signifies struggle and resistance, whereas the figures gathering are emblems of that same labor needed to survive in a tougher world. The Silver Age represents an age where morality, trust, and social harmony started to fade away, requiring effort just to subsist. Editor: Yes. The composition guides us across this evolving labor; that clear tonal divide—light sky above heavy dark forms—highlights the tension between heaven's grace and earthly demands and foreshadows more decline and industry to come. I would have never have interpreted all that without understanding these classic iconographies of labor and domesticity, especially through such a striking spatial layout.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.