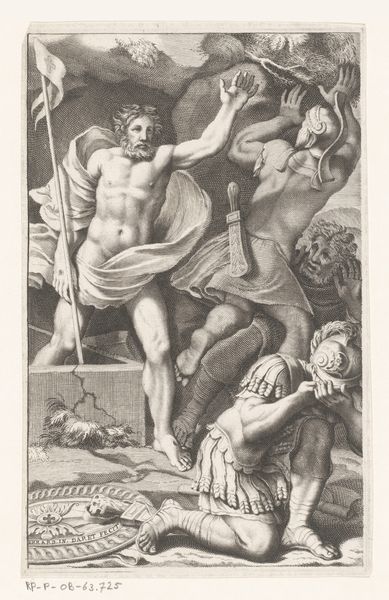

Entombment of Christ, two men lifting Christ into a tomb, with a shroud underneath the body, three crosses on Golgotha beyond, from a series of five engravings after the destroyed or detached frescoes of 1532/33 by Giovanni Antonio da Pordenone in the cloister of S.Stefano, Venice 1651 - 1661

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

men

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

christ

Dimensions: sheet: 6 1/4 x 7 1/8 in. (15.9 x 18.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Oh, what a somber dance this print creates. This is Giacomo Piccini's "Entombment of Christ," created between 1651 and 1661. He's working from earlier frescoes by Pordenone, translating paint into the crisp lines of an engraving. Editor: The figures are so stark. It strikes me as a very raw, physical rendering. All I see are those bodies straining and that lifeless weight they’re bearing, etched into the page with this kind of, well, brutal honesty. Curator: Absolutely. The engraver meticulously renders muscle and sinew, focusing on the labor itself. Look at the way Christ's body sags, and how the figures really heave! You can practically feel the grit of the engraving process—the pressure, the resistance of the metal. Editor: And what was the intended purpose of such a piece, produced via a medium of labor-intensive, manual craft and distributed as multiples? Did its relative availability change how people engaged with its subject matter? Curator: Prints like this had multiple functions. Certainly, they served as devotional aids, bringing religious scenes into homes, making them far more accessible than large-scale paintings in churches. But they also disseminated artistic ideas, helping spread the visual language of the Baroque. And they were a valuable commercial enterprise. Editor: It is fascinating how commercial value is assigned, from the labor in crafting the medium itself to the story's cultural value that it conveys, isn't it? The cross-hatching, creating a play of light and shadow; is that just skillful replication or is it itself interpretive and therefore holds value of the creator as well? Curator: Exactly! These engravers weren't mere copyists, but interpretive artists in their own right, breathing new life into the master’s compositions and disseminating it on a broad scale. There's real artistic input. They added layers to the narrative, adapting and enhancing it for their time. Editor: Thinking of artistic interpretation brings me to how it impacts viewers such as ourselves centuries after it was originally made. For me, what lingers isn't just the biblical story but the tangible sense of the weight being lifted and laid down in our world today. It connects this almost abstract, antique artistry to something profoundly relevant, human, and in reach.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.