engraving

#

pen drawing

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: width 195 mm, height 249 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

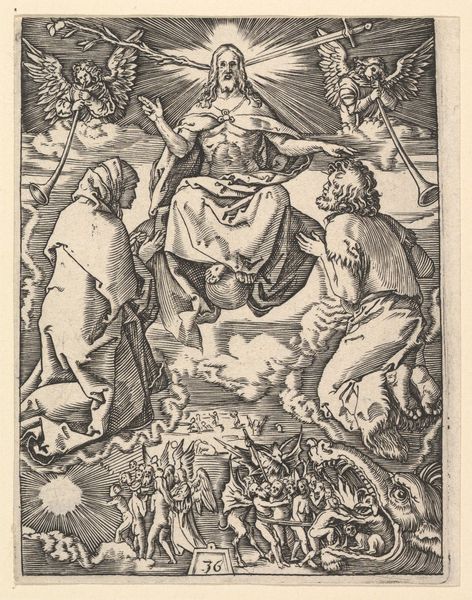

Curator: The work before us, "Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane," was rendered by Dirck Volckertsz Coornhert in 1548. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum and created via engraving. Immediately, I am struck by how much activity is contained within. What's your initial reading of it? Editor: It looks intensely melancholic, almost claustrophobic, rendered in very fine lines. The scene feels heavy, as though laden with sorrow, and you can see the lines working to delineate form, texture and shadow, building depth from almost nothing. What’s interesting, in the method of its production. Curator: The work portrays Christ's agony the night before his crucifixion. We see him kneeling, an angel offering him a cup symbolizing his fate. Below, the disciples sleep, oblivious. In the distance is a glimpse of the events that will come to pass in his near future. It serves as a visual encapsulation of a pivotal moment in religious history, heavily symbolic. Editor: Absolutely. Consider the technique – engraving requires meticulous labor. Coornhert would have used metal tools to carve these lines into a plate, building up the image bit by bit. This lends itself well to images of moral clarity. Look at the sleeping disciples. I want to explore this contrast in action through manual, reproductive process! It feels extremely relevant to understand this through craft production. Curator: Sleep is frequently used to evoke that moment where the call for help falls to dormancy. Look at how each detail adds to the gravity. The angel appears above, as does the looming execution—the scene laden with premonition. The chalice held by the angel carries powerful symbolic meaning that reverberates even now. Editor: And those materials, the copper plate, the ink… these weren’t just aesthetic choices; they were deeply intertwined with the available technology of the time, informing how the artwork was made and disseminated, and who had access to it. It grounds the religious experience, paradoxically. Curator: The imagery pulls on well-known theological representations that coalesce around grief and redemption. To experience it as a symbol with a reproducible base shifts our understanding of it. Editor: Seeing the material reality helps to reveal those earlier meanings. It is like touching the past. Curator: Indeed. Hopefully, we've provided some insights into the image itself and how an understanding of iconography opens up additional perspectives for considering meaning. Editor: And appreciating the engraving's production and materiality provides a concrete access point to engaging with its historical and social significance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.