ink

#

medieval

#

ink

#

geometric

#

islamic-art

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: 10 1/2 x 8 in. (26.67 x 20.32 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

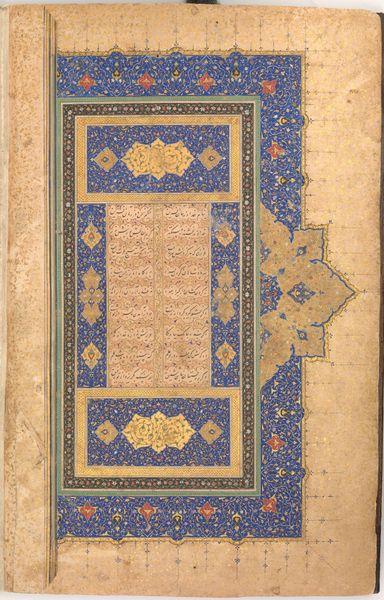

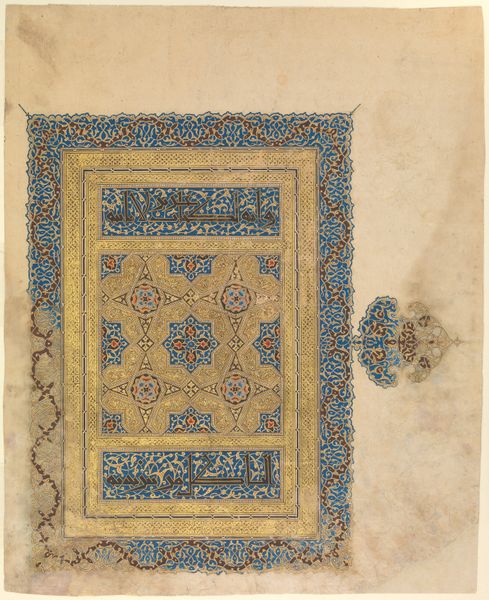

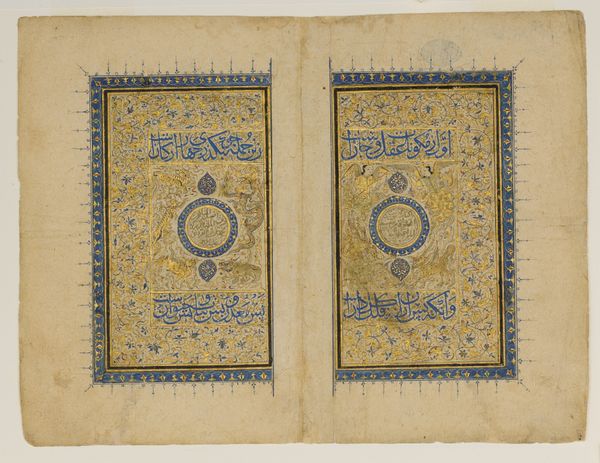

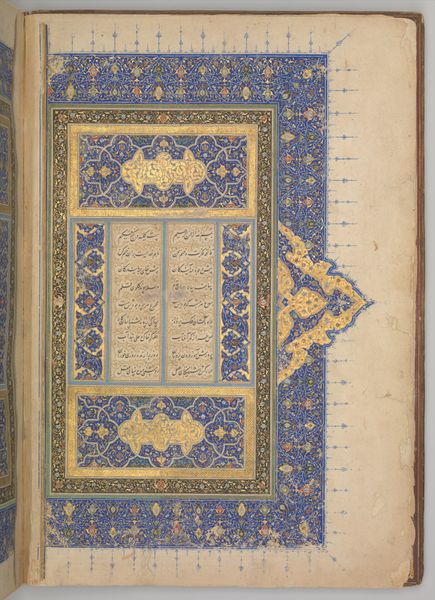

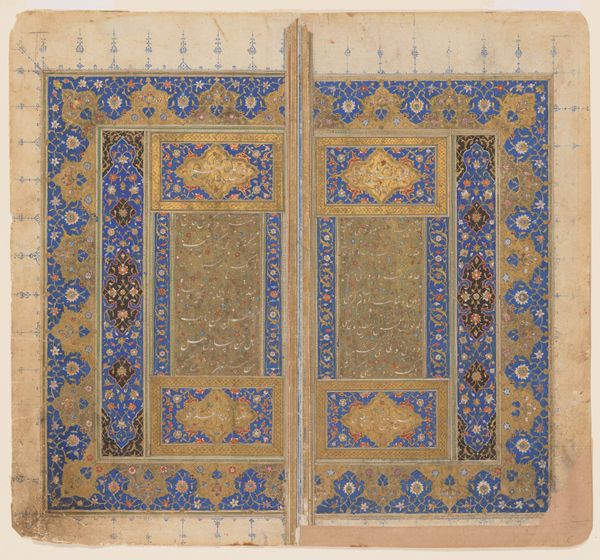

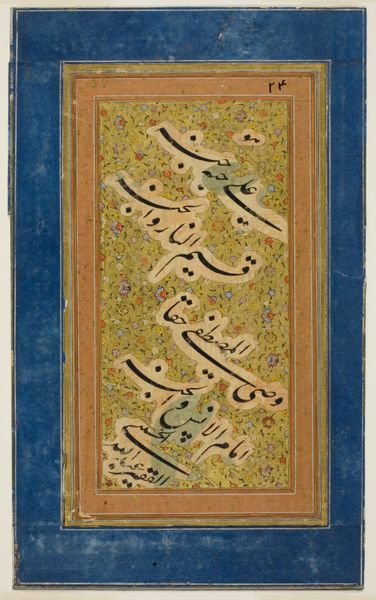

Curator: This illuminated page comes from the Koran, dating back to around the 12th century. It resides here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. I’m immediately struck by the dense patterning. What captures your attention? Editor: For me, it’s the interplay between the stark geometry of the Kufic script and the flowing, almost organic, ornamentation surrounding it. There's a kind of controlled energy in the composition. You get a sense of both structure and freedom coexisting. Curator: Absolutely. Thinking about the materials used – primarily ink on parchment – it's a testament to the skill and the labor involved in creating such a piece. Preparing the parchment, mixing the inks from natural pigments, the painstaking process of calligraphy itself. It represents an enormous amount of effort and a kind of devotion. Editor: And when we consider the social context, this page wouldn't have been just an aesthetic object; it was a vital part of religious practice, central to Islamic intellectual and spiritual life. Its production reflects a broader system of patronage and craft guilds that flourished during the medieval period. And while created by individuals it represents more then a sole artisan’s point of view. Curator: Exactly, there's this tension between the individuality of the artist, likely a highly trained calligrapher, and the constraints imposed by tradition and religious doctrine. How would you say the calligraphic style, particularly the angular Kufic script, contributes to the overall meaning of the work? Editor: Well, Kufic script, with its clear, monumental quality, communicates authority and permanence. This particular style connects this piece to its specific era in Islamic intellectual history, especially the use of the red marks that aided in the pronunciation of certain texts. As an artifact, it stands to promote language justice today and honor accessibility of religious material. Curator: It's a powerful example of how material choices and artistic techniques were inextricably linked to cultural and religious values in the medieval Islamic world. This intersection of form and content reveals to modern eyes that the historical value of an object rests also in its artistic execution. Editor: It’s work like this, that makes one recognize the immense labor and skill in material making practices of the era while offering crucial opportunities for interfaith and intercultural discussion. Curator: I agree. Considering its age, the page stands as a testament to the dedication and meticulousness embedded within this work. Editor: Indeed. A reminder of the stories objects tell about belief, skill, and human ingenuity across time.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart almost 2 years ago

⋮

The earliest Korans were written almost exclusively in the script known as kufic, after the town of Kufa in Mesopotamia where the style originated. Until the eleventh century, letters were thick and well-rounded, with short vertical and pronounced horizontal strokes. In later examples like this however, letters appear more angular with a stronger emphasis on the vertical elements. This form of kufic eventually gave way to more fluid cursive styles, including thuluth, naskhi and nastaliq, probably the most elegant Persian script. In this example, the rich background of muted arabesques heightens the angularity and strength of the script itself.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.