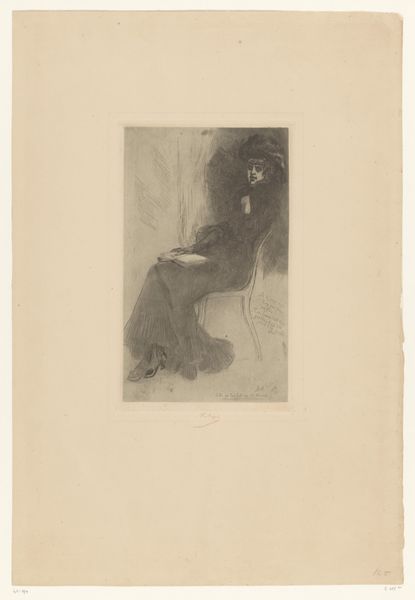

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

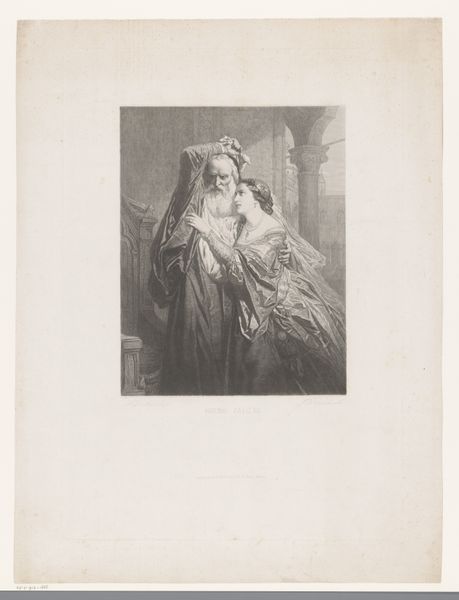

figuration

#

pencil

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 418 mm, width 304 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

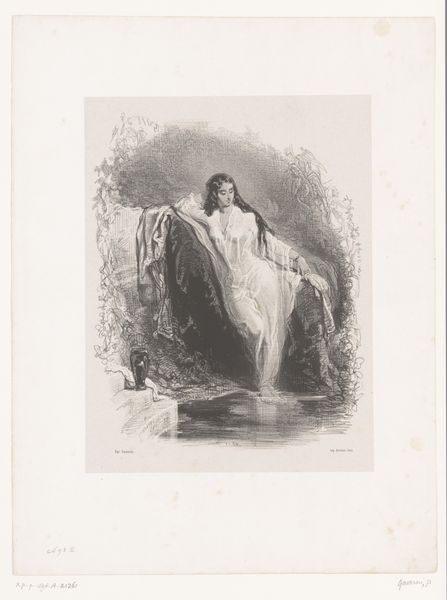

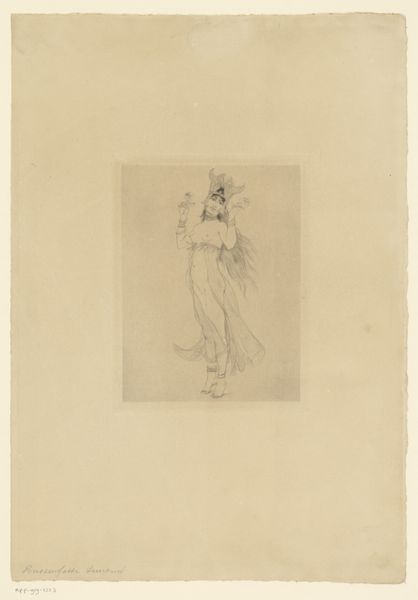

Curator: Looking at "Lezende Vrouw," or "Reading Woman," a pencil drawing by Henri Patrice Dillon created sometime between 1860 and 1909, I’m immediately struck by the deliberate softness of line and wash of light. Editor: Yes, there's an ethereal quality to it, almost as if she's fading into the page itself. I find myself wondering about the social implications of a woman captured in the act of reading during this period, especially given the limited access to education and intellectual pursuits afforded to women. Curator: Certainly. And if we consider the materials and production, it's crucial to understand this isn’t a grand history painting, but a pencil sketch. Pencil, as a readily available material, democratizes artistic production, placing the capacity to create in more hands. Editor: Precisely, and by viewing this through a lens of gender and class, we begin to unpack not only the individual portrait but also the societal power dynamics at play. Was this reading woman empowered by knowledge, or trapped by societal expectations? Who could even afford being portrayed like this? Was Dillon challenging conventions or reinforcing them? Curator: It’s compelling how Dillon utilizes the medium, creating depth using subtle shading, guiding our eyes from the delicate coiffure down to her hand gently poised over the page. Pencil lends itself beautifully to that level of nuance and intimacy. Consider too that Dillon could have been working in preparatory sketching or working on smaller scale commissions. Editor: It’s tempting to interpret the scene as passive—a woman quietly reading, a timeless theme. However, when contextualized within the socio-political sphere of the late 19th century, her very act of reading becomes potentially subversive. Perhaps the open book isn't just a prop but rather symbolizes a gateway to empowerment, challenging restrictive social norms. Curator: It’s about labor too, of course: both hers, in occupying her mind through reading, and Dillon’s in the painstaking process of translating her image to paper, using relatively meager and industrially-produced materials to depict that private moment. Editor: Thank you, the conversation has helped me reconsider how social and personal reading acts, as the artist may not have had agency over the viewers reactions, nor could ever predict it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.