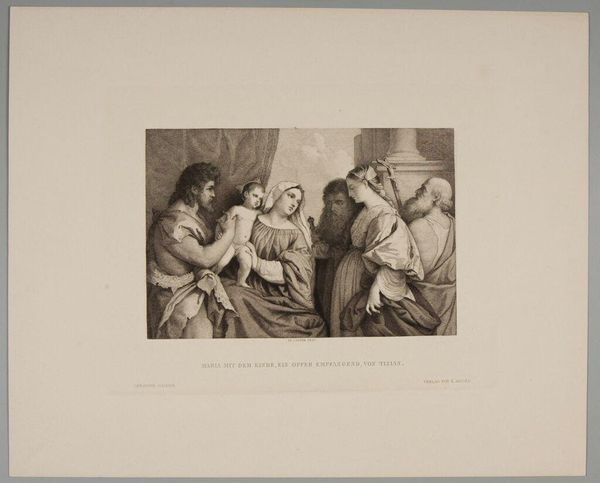

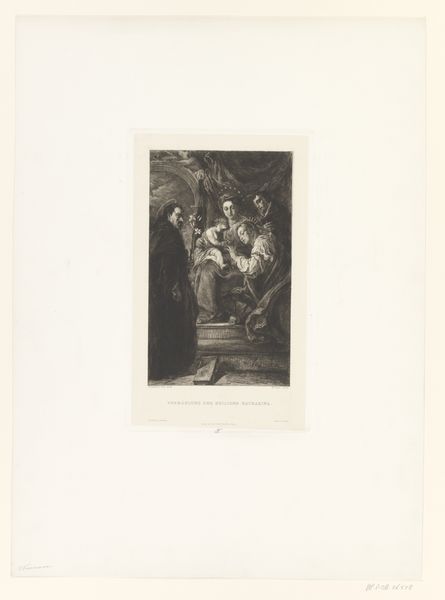

Maria met Kind en de heiligen Catharina en Johannes de Doper 1810 - 1875

0:00

0:00

moritzsteinla

Rijksmuseum

print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 363 mm, width 457 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Maria met Kind en de heiligen Catharina en Johannes de Doper," a print made by Moritz Steinla sometime between 1810 and 1875. It’s currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. I'm struck by how…soft everything appears despite being an engraving. What do you make of it? Curator: The softness is interesting, isn’t it? Consider this within the context of Romanticism. We often think of grand historical canvases, but here, Steinla uses printmaking to disseminate a kind of domestic piety, associating it with idealized historical figures. Note how the very *act* of reproducing this image—making it widely available—shapes its cultural role. It transforms religious iconography into a commodity for bourgeois consumption. Editor: So, it’s not just *what* is depicted, but *how* it’s distributed? Curator: Precisely. This image exists not in a church, demanding reverence through architectural grandeur, but potentially in someone’s home. Its power shifts from divine authority to personal reflection. Who do you think was more likely to own something like this? A clergyman? A nobleman? Editor: I would guess a family. Maybe a middle class family trying to seem high class? Curator: Exactly! These types of popular religious works blur the line between art and moral instruction. Editor: It's fascinating to consider how the means of production influence the art’s social function, far beyond its aesthetic qualities alone. Curator: Yes. And by analyzing this, we see how artistic value is conferred not just by the artist, but by institutions, societal norms, and, even by those who possess the image. This makes even a seemingly quiet piece a powerful tool in shaping culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.