relief, bronze, sculpture

#

sculpture

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

relief

#

bronze

#

figuration

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

#

history-painting

Dimensions: overall (without extruded corners): 6.93 × 5.15 cm (2 3/4 × 2 in.) gross weight: 65.19 gr (0.144 lb.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

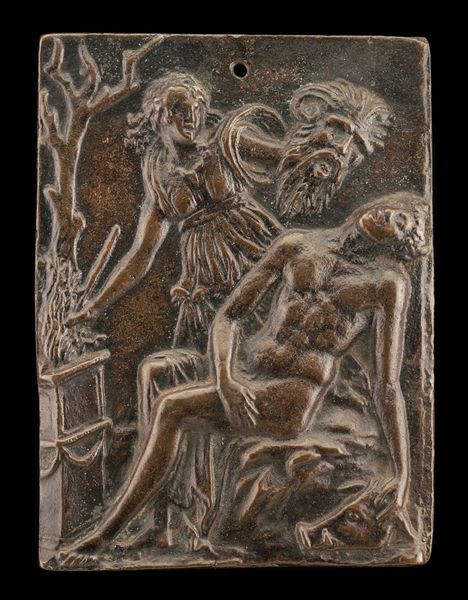

Curator: Welcome. Today we're examining "Apollo and Marsyas," a bronze relief likely created in the early 16th century. It's a fascinating depiction of a pivotal moment in Greek mythology. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the palpable tension. Apollo exudes an almost arrogant calm while Marsyas, captured mid-dance, appears unaware of the looming doom. There’s a stillness to the form. Curator: Indeed. This relief encapsulates the story of their musical contest, judged—unfairly, many would argue—by King Midas. The aftermath, as the myth tells it, is notoriously gruesome; Apollo flays Marsyas alive for daring to challenge his artistic superiority. Editor: Which immediately forces a reading that questions the narrative itself. Is it truly a celebration of divine talent, or a condemnation of unchecked power and brutal silencing of dissenting voices? You immediately feel the unfairness of a system weighted against the challenger. Curator: The piece speaks to the social order of the time it was crafted, of course. Artists during the Renaissance often used classical narratives to subtly comment on contemporary power dynamics. Consider how guilds, patronage, and even artistic academies operated then; it mirrors, to some extent, this struggle between an established authority and a newcomer. Editor: And we have to think about the legacy of this particular myth: artistic innovation versus institutional control, high art versus folk traditions. Marsyas was a satyr, linked to the wild and Dionysian, a challenge to Apollo’s structured, harmonious world. Look how this bias gets reproduced here, in a work immortalizing a moment of cruelty and exploitation in what, historically, had often been read as simply a story of triumph. Curator: What do you make of the medium? Bronze, of course, lends a certain gravitas, linking back to classical sculpture and legitimizing the narrative, but I find it compelling when put against the context you rightly introduce. Editor: The burnished surface and high relief gives a weight to the figures that feels... oppressive. And the detail on Apollo’s robes versus Marsyas’s more roughened form even feels loaded—literally, representing status. Curator: Ultimately, a piece like this makes us question not just what the artist intended, but how successive generations have interpreted, and perhaps justified, hierarchies of power through art. Editor: Right, it’s a visual embodiment of how narratives get shaped—and who gets to do the shaping. Let’s not take stories at face value but understand the societal underpinnings that enable their distribution. It offers critical space for deconstruction of the myths and histories we think we know.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.