Copyright: Public domain

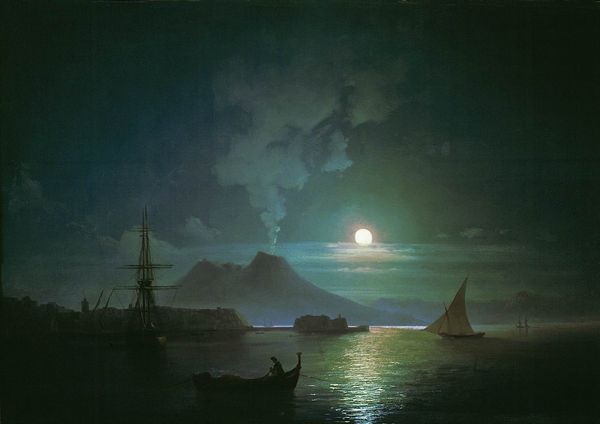

Curator: Ivan Aivazovsky’s "Windmill on the Sea Coast," painted in 1851, is a compelling example of 19th-century Romanticism rendered in oil. Look at how the scene unfolds, drawing the eye across water and land to the celestial drama above. Editor: My first thought? Melancholy. There's a quiet stillness, even with the implied motion of the windmill. The muted palette and solitary figures evoke a sense of isolation, perhaps reflecting a deeper yearning for connection to both nature and community. Curator: That reading aligns with Aivazovsky's own historical context. He lived through periods of significant political and social upheaval in Russia, where he sought solace and inspiration in the sublimity of nature, presenting an interesting contrast between nature and burgeoning industrialization. The windmills weren't just for the community they served but rather were, too, aesthetic choices. Editor: Exactly. This windmill stands tall in the foreground. How much does the architecture tell of progress versus the overwhelming nature and moonlight speaking about natural beauty and simplicity? Also, whose labor built and maintains it? Curator: And don’t forget Aivazovsky’s seascapes, with their captivating light, contributed to a broader national identity. It created symbols which helped create and bolster Russia's imperial ambitions during a period of intense nationalism. The artist became an icon of Russian art culture because the work helped build national fervor, not just a scenic painter of beautiful places. Editor: That’s a powerful reminder. So the shimmering sea becomes not just a landscape feature, but an assertion of power, of national presence, against other rising empires. A subtle claim being painted right into the canvas and the imagination. And that light isn't just a beautiful effect; it's strategic illumination. Curator: Precisely. Understanding the artistic, societal, and imperial history provides critical tools. How should museums then display these works so audiences better comprehend them and can have important and critical engagement? How do we talk about something both gorgeous and deeply embedded in colonial expansion? Editor: It's vital that galleries promote difficult dialogue, making connections between romantic aesthetics and the social realities, emphasizing how those realities impacted and were impacted by everyday life, economics, class, and empire-building agendas. "Windmill on the Sea Coast" isn’t just a beautiful painting; it's a portal. Curator: Agreed. Bringing different voices and readings like these help to illuminate the richness, revealing its complexities, making the artwork a meaningful contribution. Editor: Yes, pushing us to consider our relationships with history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.