Copyright: Public domain

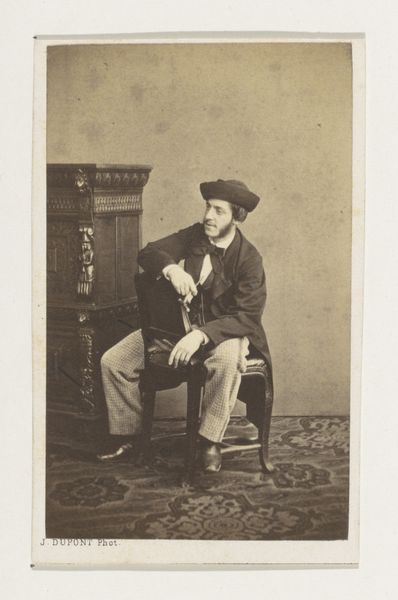

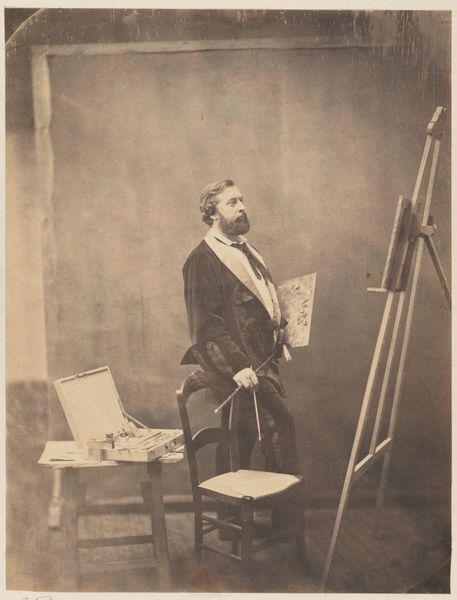

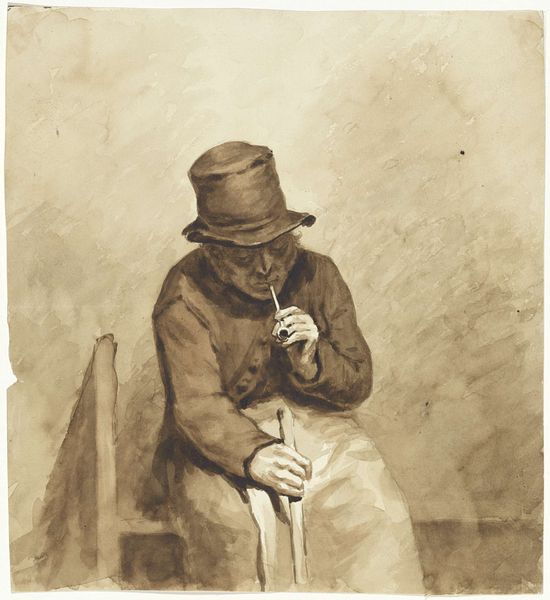

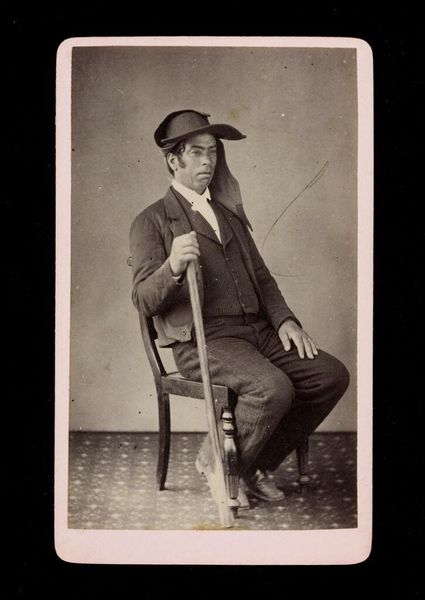

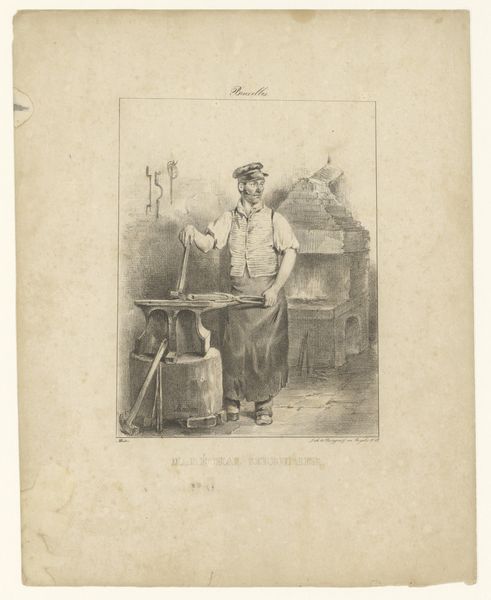

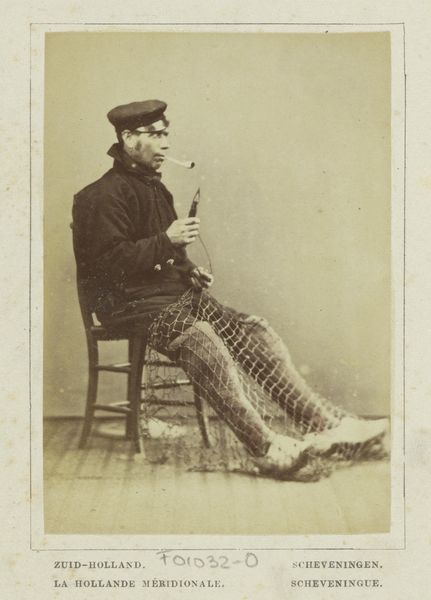

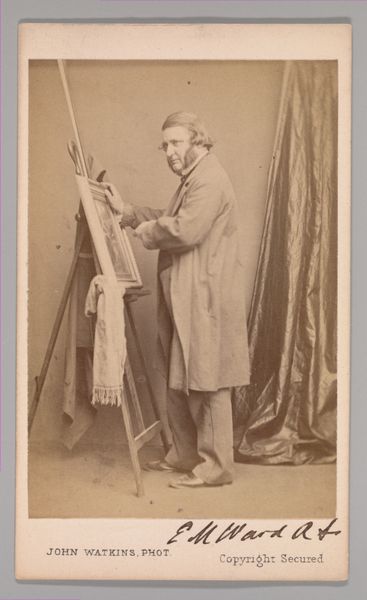

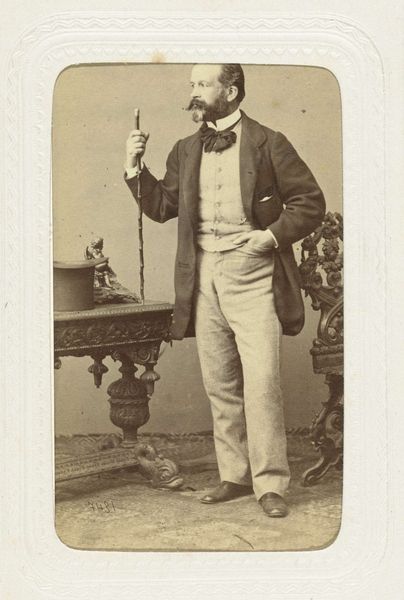

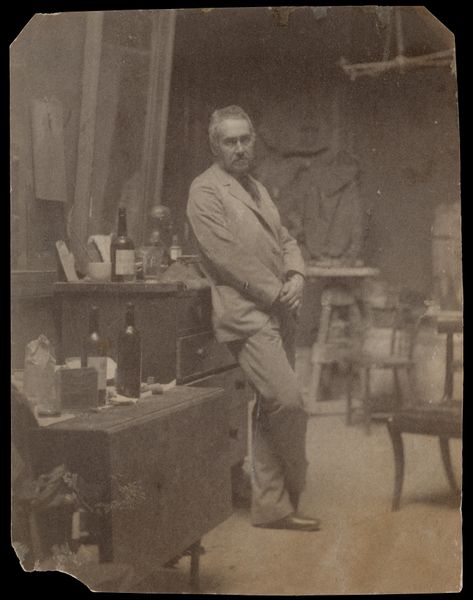

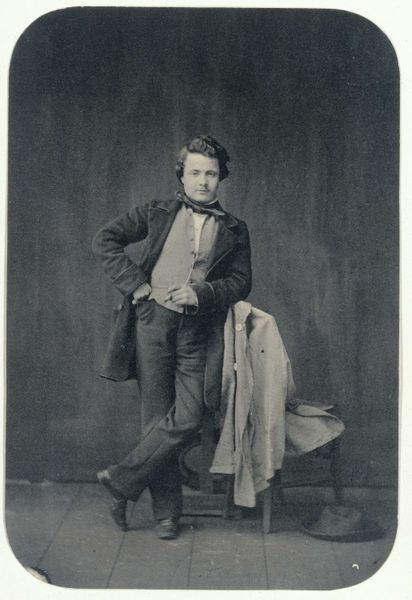

Editor: Frank Eugene's "Schachspieler (Dr. E. Lasker und sein Bruder Dr. B. Lasker)" from 1908, presented in a daguerreotype, gives off such a wonderfully staged and intimate feel. What is your interpretation of it? Curator: Well, beyond the surface of the image itself, consider the socio-economic context of photography at the turn of the century. The daguerreotype, with its unique material properties, elevates the status of photography. Was this photographic method easily accessible? No. The labor, from posing the subjects to developing the image using specialized chemical processes, represents an investment in creating a portrait meant for an elite audience. What’s more, the presence of painting, and an artist-like subject in an intimate creative workspace blurs lines between photography as mechanical process and as ‘art’. Editor: That's interesting. I never considered how the medium would reinforce class boundaries. Are you saying that even the materials themselves become a statement? Curator: Precisely! And consider the backdrop. Is it a meticulously crafted set, designed to project an aura of bourgeois sensibility and high culture? It isn't neutral. Every material object that composes it, from the stove and tools of art, to the artist clothing and posing is imbricated into and partakes in constructing a specific image tied to certain means and status of its subject. These portraits, more than simple representations, function as markers of distinction, signifying social and cultural capital. Editor: That completely reframes my view of it. Thanks for drawing attention to those markers. Curator: Thinking about the relationship between artistic labor, representation, and material production opens up many avenues of investigation, and I’m glad you see how potent the combination of those are here.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.