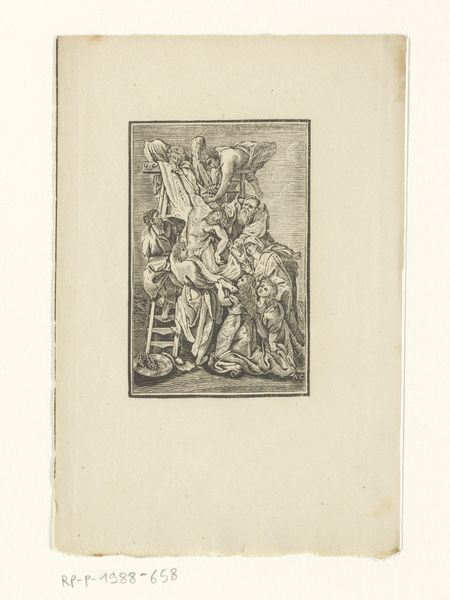

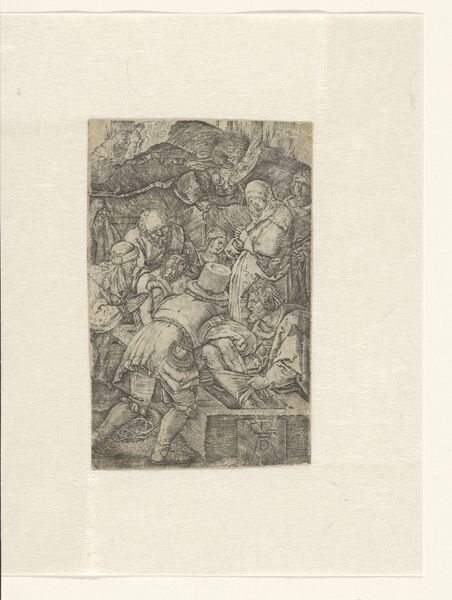

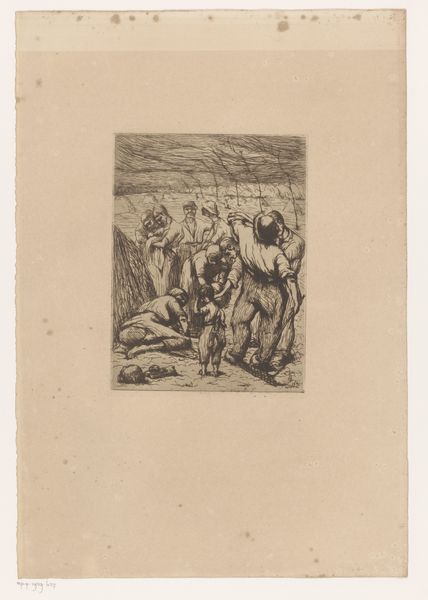

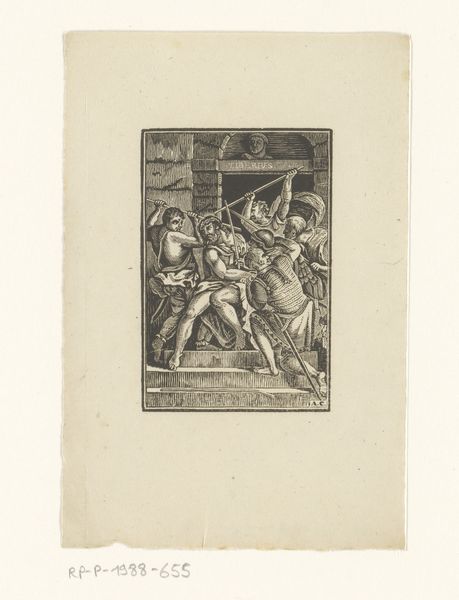

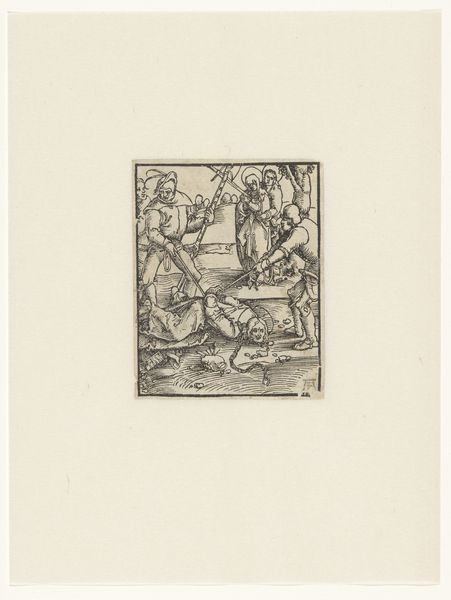

print, woodcut, engraving

#

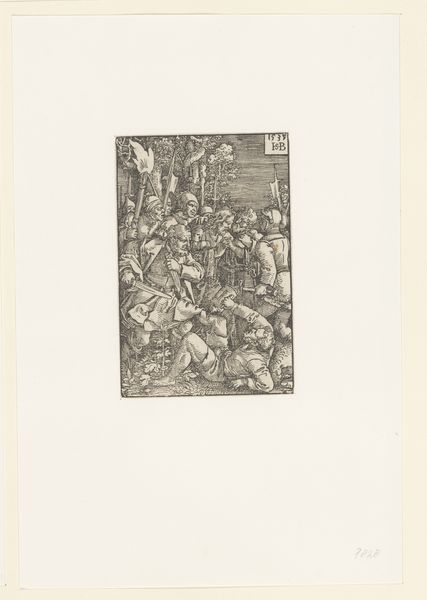

medieval

#

narrative-art

# print

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

woodcut

#

line

#

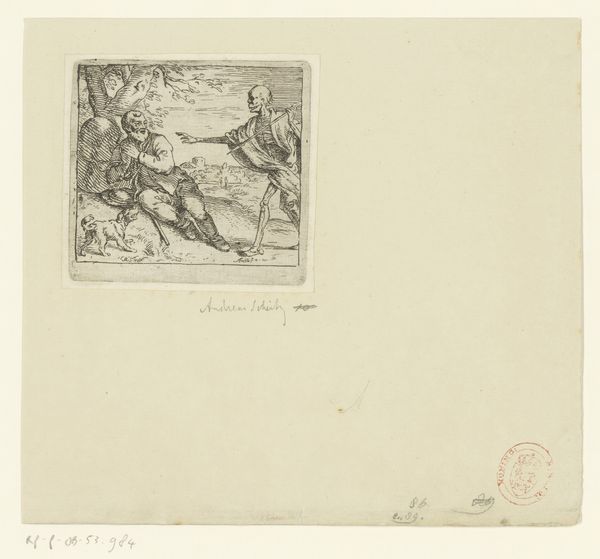

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

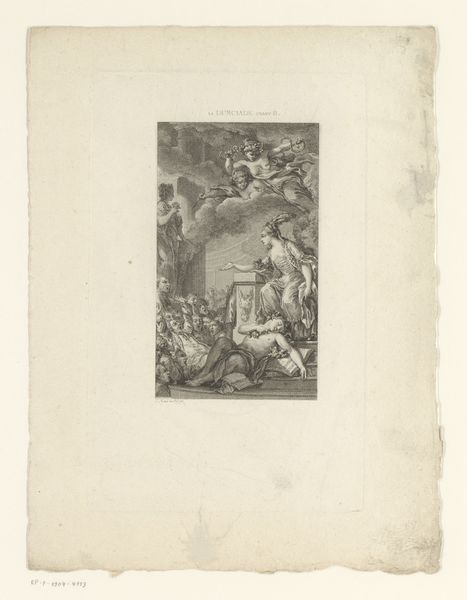

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 65 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We’re looking at "Blinde man en de Dood" – "Blind Man and Death" – a woodcut from 1547 by Hans Holbein the Younger, at the Rijksmuseum. It's a stark image. The high contrast and very clear lines give the scene a sense of immediacy and drama. What jumps out at you in terms of visual structure? Curator: Indeed, the immediate dichotomy presented by the crisp lines emphasizes form. The composition itself is striking, isn’t it? Consider the positioning of Death in relation to the blind man. Note the directional lines leading our eyes diagonally across the image, highlighting their meeting. Holbein compels us to observe that one cannot be aware of their own demise. The engraving showcases the master’s talent for carving figures through cross-hatching and rigorous parallel strokes. This gives substance and, ultimately, a tactile form in an essentially untouchable medium. Editor: So, you're saying the physical carving technique really underscores the themes of mortality and awareness? Curator: Precisely. Consider how the lines give form and suggest movement and texture: the rough hewn clothes of the figure against the smooth starkness of Death's bones. How do these formal elements work together to express these intangible ideas? Editor: The use of line and texture to give tangible form to intangible concepts, such as fate and hope – it’s something to consider. The intensity and direction certainly give an evocative push and pull. I can see how the engraving's qualities highlight meaning. Curator: An important revelation in our analysis of art history's role, wouldn’t you agree?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.