oil-paint

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

romanticism

#

animal portrait

#

genre-painting

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

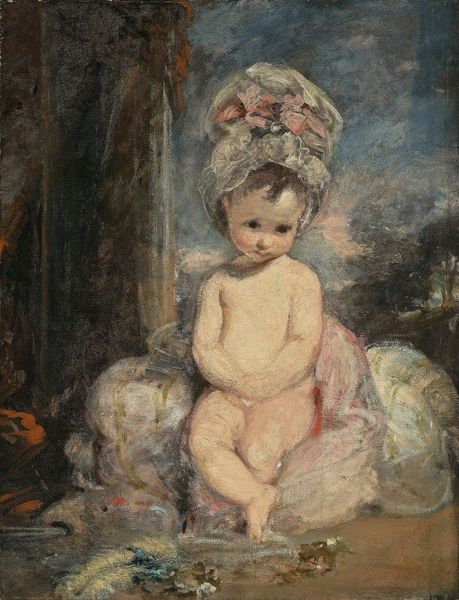

Curator: This is John Hoppner’s "Girl with a Rabbit," painted around 1800. Its depiction of childhood innocence is quintessential Romanticism. Editor: Immediately, I notice the somber tone, achieved through those earthy browns and muted greens. The thick, almost gloppy oil paint application definitely conveys a sense of the tangible, grounding the subject. Curator: The sitter, likely from an upper-class family, is posed with a rabbit, a common symbol of innocence and purity at the time, but there are complex colonial histories embedded here. Rabbits, along with other domestic animals, were being aggressively introduced and integrated into colonial economies to "improve" landscapes and displace local ecologies, symbolizing British domestic and agricultural dominance in the landscape. Editor: Interesting point. On the surface though, it’s that striking contrast that grabs me. You have this soft, warm light illuminating the girl and the rabbit while they sit engulfed by this dark background. The brushwork itself contributes to this mood—almost sculptural in the way it models the forms. Were pigments so easily available? I find myself wondering who ground and mixed them. Curator: That is a crucial question to ask, certainly. And your comment about the contrast reminded me—the darkness could also reflect the social anxieties around childhood vulnerability during that period. Infant mortality rates were high, childhood illnesses were common. The preciousness of the girl and her rabbit is set against a precariousness of life. Editor: That contextual tension enriches the experience for sure. What does the painting's materiality tell us, though? Those visible brushstrokes are a testament to Hoppner's hand and craft, and yet that broad, loose handling risks de-centering labor; are the social conditions which produce these paints invisible to the artist? Does their conspicuous consumption play a part? Curator: Precisely! These artistic representations, in their delicate depictions of children, often gloss over the immense wealth disparity in that era—one paid for in large measure by the production of material commodities within the colonial landscape, to be sure, but also by those excluded from Hoppner's romantic vision. Editor: So we are talking about Romanticism with its material reality check! Curator: Exactly, art always exists within this intricate framework of power dynamics. It's important to look beyond the surface to uncover its embedded stories. Editor: Yes, by recognizing materiality within historical and social dimensions we start a vital and informed engagement. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.