Copyright: Public Domain

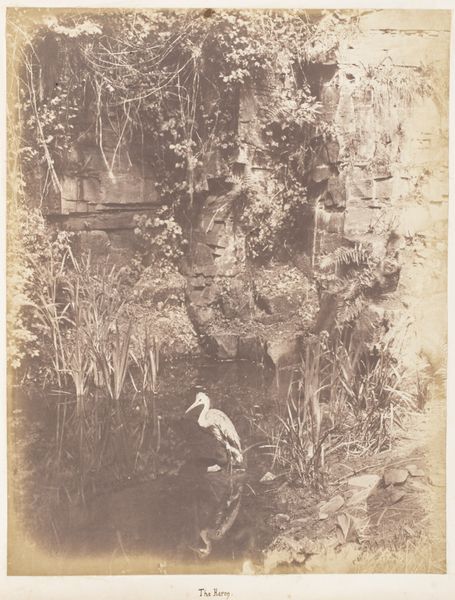

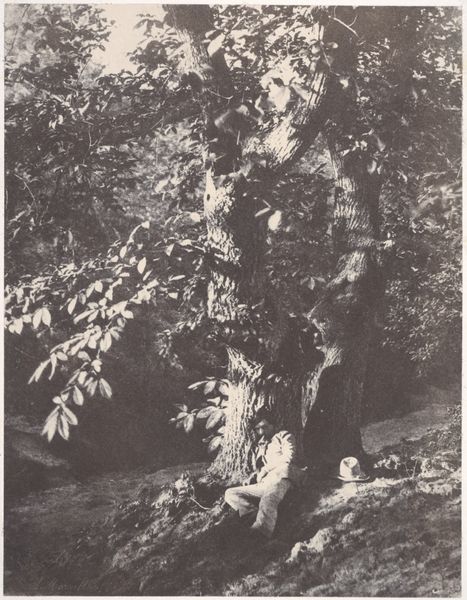

Editor: Here we have "Piscator, No. 2," a gelatin-silver print from 1856 by John Dillwyn Llewelyn, currently residing at The Met. The stillness is striking, a heron frozen in a reflective pond. What do you make of its social context? Curator: Well, consider that in 1856 photography was still relatively new. Llewelyn, a wealthy amateur, was pushing the boundaries. Depicting a heron in its natural habitat wasn't just about aesthetics. It was a statement of man’s place in, or perhaps alongside, the natural world, reflecting the contemporary Romantic sensibilities. How does this strike you? Editor: I hadn’t thought about the technology being so fresh! It feels like Llewelyn is emphasizing nature's inherent beauty. What political motivations might drive his selection of subject matter? Curator: Precisely. Photography offered a democratized means of representation, diverging from the elite tradition of painted landscapes. The very act of capturing this scene, showcasing nature to a wider audience, could be seen as subtly challenging established artistic hierarchies. Was this challenging power dynamics in imagery? Editor: So, showcasing the raw beauty was an act of rebellion in a way, wasn't it? Like making art more accessible to ordinary folks! Curator: Indeed! Llewelyn uses the relatively new medium to invite everyone to engage with nature in new ways. In effect, bringing visibility of nature to the population. Editor: Fascinating! I’ll certainly look at 19th century photography differently from now on. Thank you! Curator: My pleasure! It's crucial to view even seemingly serene nature scenes within the larger frame of social and political influences of its time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.