drawing, pencil, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

geometric

#

pencil

#

expressionism

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

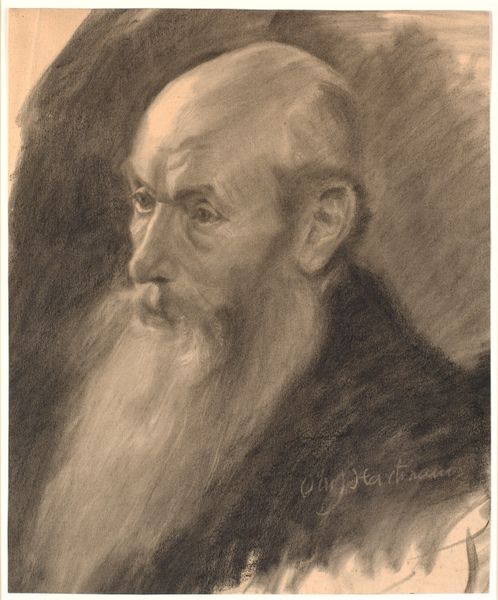

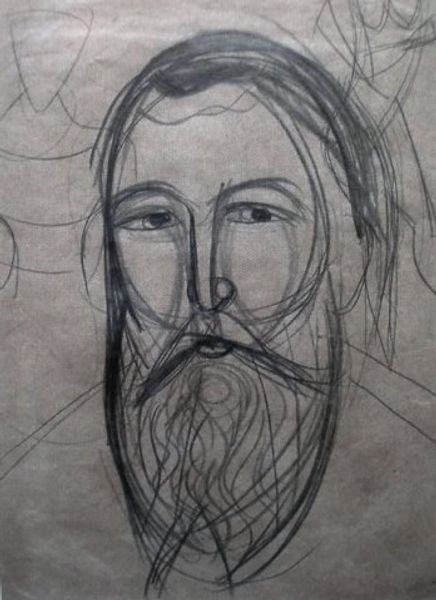

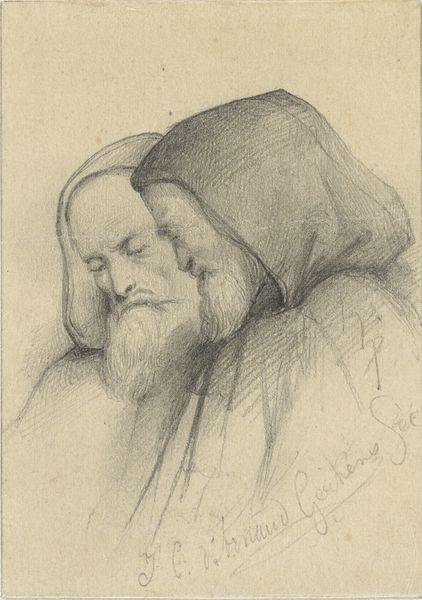

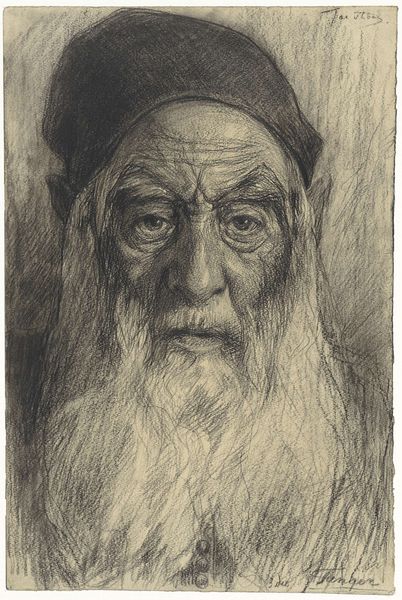

Curator: Here we have Mykhailo Boychuk’s "Andrei Sheptytskyi," a charcoal and pencil drawing from 1912. It resides here at the Lviv National Art Gallery. Editor: Wow, there's such a directness to this portrait. The man’s got such a serious, world-weary gaze. It feels like he's seen centuries pass by. You can almost smell the incense and hear the whispers of ancient prayers, can't you? Curator: Indeed. Andrei Sheptytskyi was a prominent religious and cultural figure, and Boychuk’s rendering captures that sense of gravity. Considering its time, the portrait hints at expressionistic styles which had not yet spread across Europe. But most interesting is its function: a portrait meant to be quickly understood by a public not necessarily versed in fine art. Editor: I get that. There’s something almost…folksy about it. While there’s clear skill in rendering, say, the texture of the beard or the fall of light across his face, the lines are simplified, and he's immediately recognizable as a pillar of faith, which in that era of nation-building and political instability, the figure must be very important, even essential to preserve in artistic memory. Curator: Absolutely. This piece predates Boychuk’s more renowned monumental art, but you can see the seeds of his aesthetic here. He and his peers of the Ukrainian avant-garde grappled with connecting art and national identity, so images of influential clergy such as this was an obvious starting point. Note that Sheptytskyi himself played a crucial role in fostering Ukrainian art and culture, a patron when such roles where less formalized, even suppressed, in Eastern Europe at the time. Editor: I can imagine. It makes the portrait more potent, a conversation between artist and subject about their culture and their moment. Now that you say this, I want to ask - isn't it daring to show this degree of vulnerability to create, not an icon of faith but of *a person*, who *happens* to embody faith in the public consciousness? A face so human you know what his mood is the moment you encounter this work of art! Curator: Precisely! And perhaps, as a result, its public appeal lies in precisely what seems folksy about it. It’s accessible, conveying something deeply spiritual, and deeply rooted in that period, despite feeling remarkably fresh and expressive, a bridge between his world and ours, in the present. Editor: Beautifully said.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.