drawing, pencil, architecture

#

architectural sketch

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

light pencil work

#

quirky sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

sketch book

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

cityscape

#

architecture

#

realism

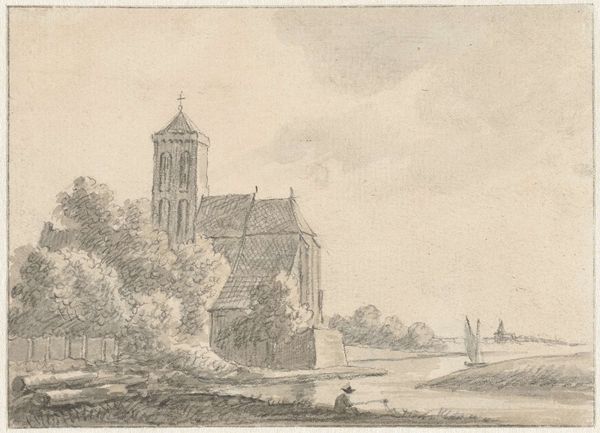

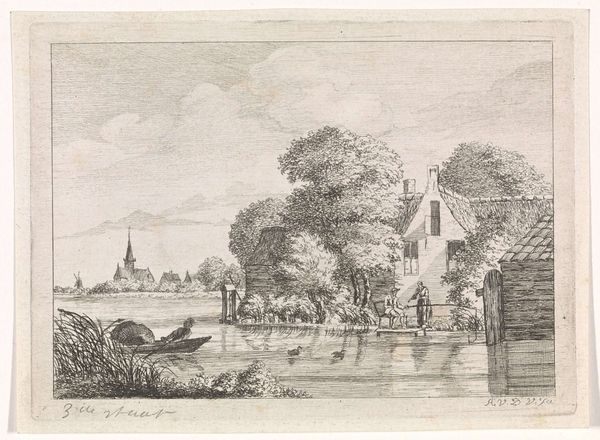

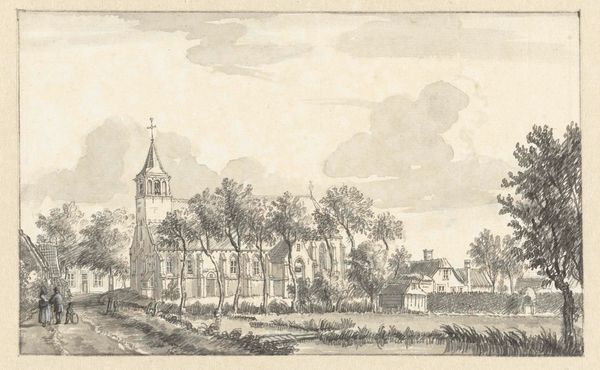

Dimensions: height 96 mm, width 153 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This tranquil pencil drawing, "Dorpskerk en huizen aan een rivier," or "Village Church and Houses by a River," is attributed to Pieter Jan van Liender. Its creation is estimated sometime between 1737 and 1784. Editor: There’s a melancholic beauty in the greyscale. The scene evokes a sense of quietude and, honestly, of detachment. The buildings seem to stand as silent witnesses. Curator: Van Liender, known for his detailed topographical drawings, seems to capture more than just the physical layout. Note how the church spire acts as a symbolic focal point, dominating yet harmonizing with the domestic structures around it. Religious and secular life are presented interdependently. Editor: Interdependence, but perhaps unequal in its representation? The prominence of the church arguably signifies the sociopolitical dominance of religious institutions in 18th-century Dutch life, shadowing even the domestic space. Curator: An astute reading! Van Liender’s meticulous style, while appearing straightforward, incorporates a worldview of order, social norms, and perhaps a certain societal hierarchy—visual storytelling deeply ingrained in Dutch cultural identity. Even the river seems to reflect a controlled landscape. Editor: Exactly. The artist uses these symbols – church, houses, and the tamed river – to reinforce notions of stability and the status quo. What is excluded is as important: where are the bodies, where are those not living according to these standards of burgher life? Curator: Absence can, indeed, carry tremendous weight. I think, given the work's existence as a sketch, this could also indicate a work in progress, a study to better understand and later celebrate this social structure that provides him patronage. Editor: Maybe, and I appreciate the nuance of understanding the patronage system in that moment. But this is more than just an innocent architectural study, I believe the composition speaks volumes about constructed realities, not merely observed ones. A potent example of the embedded ideology present in supposedly objective landscape art. Curator: It's true, what's excluded—marginalized bodies, alternative ways of being—tells its own story. Editor: Exactly! Analyzing this artwork underscores the necessity of deconstructing accepted symbols. Thanks for diving in.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.