drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

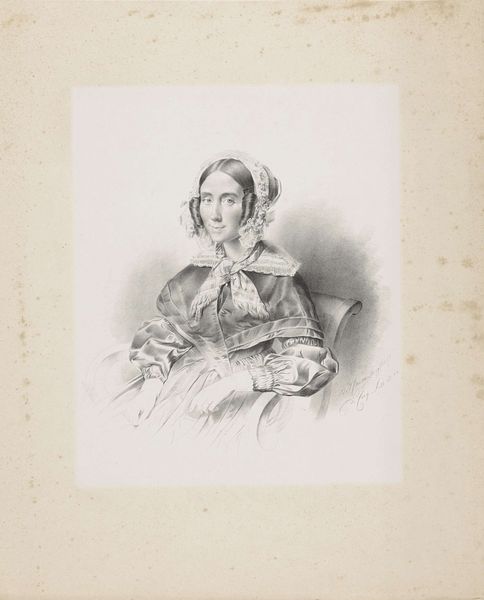

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this exquisite pencil drawing, "Portrait of a Young Woman Wearing a Cloak and Bonnet," created around 1850 by Théodore Chassériau. Editor: My first impression is one of serene melancholy. There's a quiet stillness about her, emphasized by the delicate lines of the pencil work and the subtle gradations of light and shadow. Curator: Absolutely. Chassériau, a student of Ingres, captures a transitional moment in French art history here. While rooted in academic tradition, we can also sense a move toward the emerging Realist and Impressionist sensibilities. Think about the changing roles of women in post-revolutionary France. What kind of power did portraits give women? Or take from them? Editor: That’s an interesting question, isn't it? Her bonnet and cloak, while customary, also create a sense of enclosure. I am interested in how this kind of wrapping or veiling affects our ability to visually and emotionally ‘access’ the sitter. Curator: Indeed. Consider the period's rigid social expectations around female modesty and piety. The bonnet and cloak could be interpreted as symbols of societal constraint and perhaps even enforced protection, highlighting limited possibilities. The way she holds the fabric of her cloak – it gives her control within a restrictive sartorial landscape. Editor: There’s something captivating about how her eyes meet ours so directly, almost defying the demure presentation suggested by her attire. The symbol of the eyes has appeared consistently over thousands of years representing clarity and insight. Curator: Precisely, I believe there is defiance but it's layered beneath accepted conventions. Her gaze becomes an important site for challenging societal expectations about femininity in the mid-19th century. The tension between constraint and a subtle rebellious spirit makes this work particularly compelling to me. Editor: Yes, a dialogue indeed between the seen and unseen. I feel she has communicated her truth and has asked me to respond in kind. Curator: Looking at Chassériau’s handling of light and shadow here, along with how this intersects with gender, race, and class makes it easier to create space for intersectional dialogues. Editor: Indeed. It’s remarkable how a seemingly simple portrait drawing from the 19th century continues to provoke reflection and generate meaning today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.