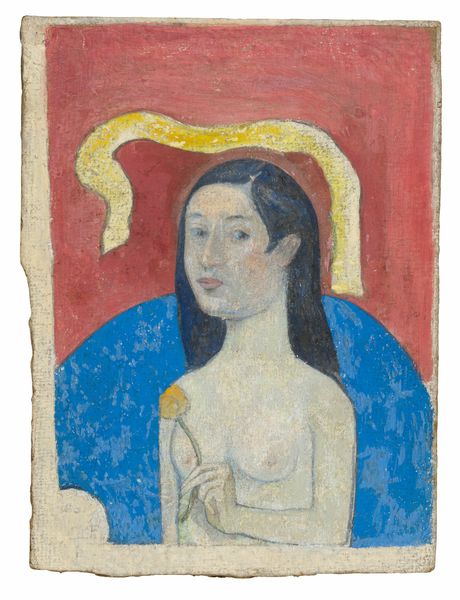

Tegel met het portret van een vrouw, oorspronkelijk gebruikt als gevelsteen in het huis Wijnhaven 16 te Delft c. 1535

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

earthenware

#

portrait

#

11_renaissance

#

tile art

#

earthenware

#

northern-renaissance

#

portrait art

Dimensions: length 31.3 cm, width 29.5 cm, thickness 3.0 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This piece immediately struck me as quietly powerful. The cracks in the glaze give it an age, a story, like lines on a well-loved face. Editor: Indeed. What we're looking at here is an earthenware tile, dating back to around 1535, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Originally, it served as a façade stone for a house in Delft, called Wijnhaven 16. Curator: A façade stone! So, this woman was quite literally holding space, supporting a building, a home. Does the museum tell us anything about her? I find myself wondering about her life, her status. Editor: Details about the sitter, or even the artist, remain elusive, but what’s fascinating is the deliberate choice of portraiture on an architectural element. It challenges the conventions of female representation during the Northern Renaissance. Rather than an idealized image, she’s depicted with a direct, almost challenging gaze, disrupting typical tropes of demure femininity. Curator: You’re right, her eyes. There's such knowing in them, almost defiant. And I adore how the anonymous artist plays with texture. Look at the softness of her draped gown compared to the sharp edges of her jeweled headdress. It feels almost playful. Editor: The depiction of her attire is intriguing. Is this a display of wealth, or something more symbolic? What does it signify to portray this person—presumably a woman—with such agency and individual expression in a public-facing context? Was this perhaps commissioned to celebrate her? Curator: Maybe it was meant to mark her strength, literally setting it in stone. This single tile suggests so much. And her slightly melancholic expression has now completely charmed me. I’m captured. Editor: This piece reminds us of how portraits were also deployed within domestic spaces as a form of political, social and ideological negotiations—which could challenge gendered forms of spectatorship. Curator: Precisely! And, standing here, looking at this beautiful tile, she becomes so very alive again. A little burst of colour on an otherwise bland Tuesday afternoon. Editor: It also demonstrates how early modern art often transcended the constraints we now place upon it. Tile, portrait, building decoration - a confluence of purpose we rarely expect.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.