painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

character portrait

#

baroque

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

christianity

#

human

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

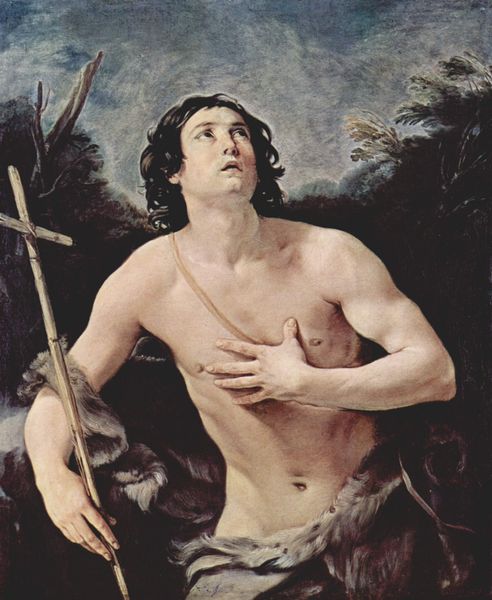

Dimensions: 146 x 113 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Here we have Guido Reni's "The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian," an oil painting completed around 1616, currently residing at the Boston Athenaeum. Editor: My initial reaction is a stark juxtaposition of sensuality and suffering. The lighting almost sculpts Sebastian's body, yet that single arrow… the whole piece feels quite staged, almost operatic. Curator: It's a carefully constructed image, certainly. Reni operated within a world where the Church dictated much artistic output. This piece, ostensibly about religious suffering, simultaneously offers the male nude as an object of aesthetic contemplation. The very patronage system of the era shaped such productions. Editor: Indeed, but look at the materials. The canvas, the pigments meticulously layered—artists like Reni were highly skilled laborers embedded in a very material economic system. I’m wondering about the sourcing of those rich dark pigments in relation to the subject matter: this devotional figure illuminated against potential sources from very distant, colonial sources. The artist uses materials to show class in a period when devotional artworks were commissioned from the wealthy. Curator: A keen point about the colonial dynamics implicit in the pigments. We should also remember the social function these paintings played. Images of martyrdom weren't merely devotional; they served as tools for the Church, reinforcing faith and demonstrating piety to the literate and illiterate. Editor: I wonder about the labor of preparing the canvas too. This wasn’t just Reni alone; assistants, apprentices... each a set of skills shaping the final product and the artist's ultimate cultural capital. It emphasizes the artistic genius' position at the peak of an artistic labor structure, creating these idealized figures as much as they are part of the real material of this class dynamic. Curator: Absolutely. The studio system highlights the collective labor masked under a single "genius." But thinking about reception, too, such works performed social functions beyond the studio, shaping collective identity, moral conduct, the performance of gender. Saint Sebastian was, interestingly, read through queer subcultures too—an appropriation outside the strictures of religious dogma. Editor: It all boils down to materials and process, from the very ground up. Even the artist’s handling of the oil paints: look at the visible brushstrokes… the build-up. Even these reveal artistic intentions. What exactly do you think this tells us about wealth at that time? Curator: Well, wealth enabled the materials to start! Ultimately, the painting gives us an entry into understanding how institutions and artistic practices interacted and formed perceptions of social identities. Editor: It gives new perspectives when we consider both the artistic techniques involved in his practice and also considering that painting is always more than just the image; its also materials, consumption and wealth all intertwined.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.