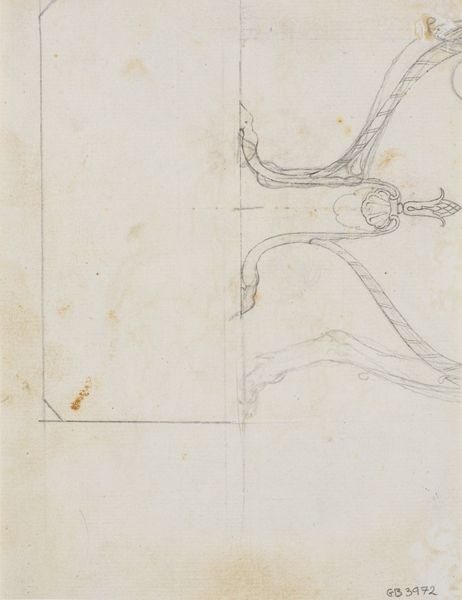

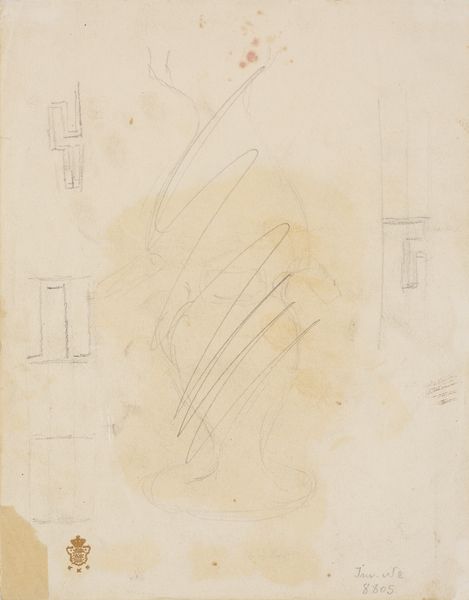

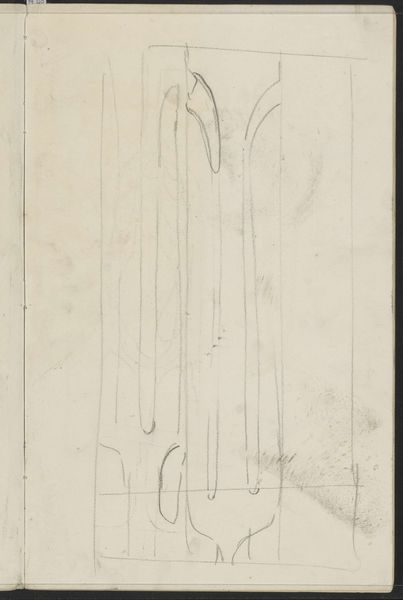

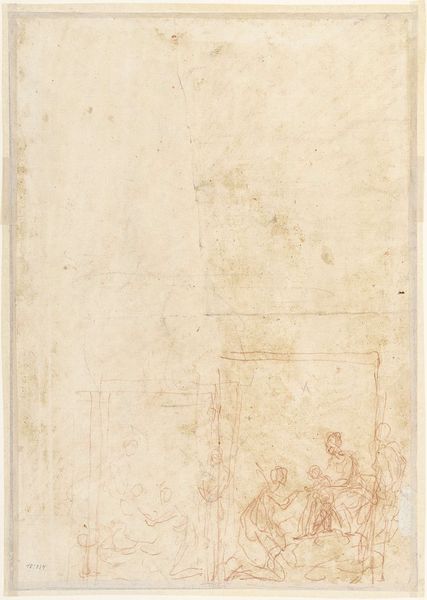

drawing, paper, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

paper

#

form

#

pencil

#

line

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 350 mm, width 277 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At first glance, I'm drawn to the sheer quietude of this work, its meditative quality despite being a design for something meant to be elevated and performed upon. Editor: Indeed. What we see here is a pencil sketch on paper, titled "Schets voor de trap van een preekstoel," or "Sketch for the stairs of a pulpit" attributed to Jan Claudius de Cock. Its creation is situated somewhere between 1678 and 1736, placing it firmly within the Baroque period. Curator: That placement helps to explain the tension between the sketched lines and the implied grandiosity. Knowing it’s Baroque, I start thinking about power dynamics, the church, and the performative aspects of religion in that era. Was this a literal ascent, or a metaphor for spiritual striving available only through social institutions? Editor: Exactly. Notice the architectural draftsmanship, which indicates the careful consideration given to material and labor. Each line suggests hours of precise work needed to realize such a structure in stone or wood. It moves beyond spiritual consideration. This isn’t merely about design, but about the labor, skill, and economic systems needed to bring such pulpits to life. Who were these craftsmen? How did their daily lives shape these forms of faith? Curator: Absolutely. The fact that it's a sketch highlights that division of labor. We see the elite vision, but where's the voice of the artisan, the underpaid hand whose life literally shaped the sermons’ very foundation? Editor: And let’s not forget the material’s accessibility. Paper and pencil denote preliminary stage; were these readily available, influencing greater design creativity? Or exclusive to an elite class restricting labor creativity. Curator: A fascinating point about accessibility. Perhaps its ethereal quality, then, stems not from spiritual intent, but economic realities - the contrast between an ambitious vision constrained by very real material limitations. Editor: Right. Looking at it again, knowing its context, brings new appreciation for what's visible, but more for what isn’t. The hands, the materials. Curator: Ultimately, it’s a beautiful reminder that any object—even one as seemingly straightforward as an architectural sketch—can be a portal to much wider conversations about faith, labor, and society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.