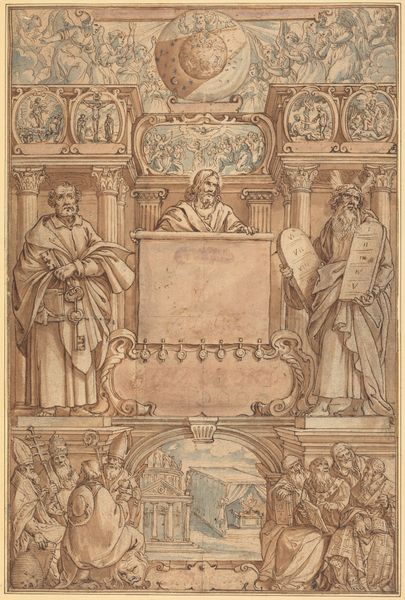

Saint Charles Borromeo Entering the Town of Pavia: Design for a Wall Decoration c. 1604

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink, graphite, pen

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

line

#

graphite

#

pen

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 153 × 310 mm (primary support); 157 × 313 mm (secondary support)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This sepia-toned drawing, “Saint Charles Borromeo Entering the Town of Pavia,” was created around 1604 by Cesare Nebbia, using pen, ink, graphite on paper. It’s such a bustling scene, full of people welcoming what I presume is a very important figure. What grabs your attention in this piece? Curator: The process itself fascinates me. Think about the material constraints: the cost of paper, the labor involved in grinding pigments for the ink. This wasn't a casual sketch. This was likely a preparatory design, a step in a much larger cycle of production, perhaps for a fresco or tapestry intended for the elite. Note the repetitive figures, like stage props--how does that affect your view? Editor: I see what you mean. It’s like the people become almost a patterned element rather than individuals. So the artist is almost designing for mass production? Curator: Not mass production as we understand it now, but certainly for a visual effect meant to impress many. The materials themselves, the pen, the ink, become tools in the service of power. And consider the social context of Saint Charles; his influence on Counter-Reformation policies shaped art production itself. Did Nebbia face limitations given Saint Charles’ dictates? Editor: So the cost and availability of the materials, the purpose of the artwork, and even the sitter himself—Saint Charles—all informed the production of this image. I guess it really highlights how art is always tied to the conditions that make it possible. Curator: Precisely. Looking beyond the purely aesthetic allows us to understand the drawing not just as an image, but as a document of labor, faith, and the material realities of 17th-century life. Editor: It definitely gives me a new appreciation for everything that goes into a work of art, even something that looks like a simple sketch.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.