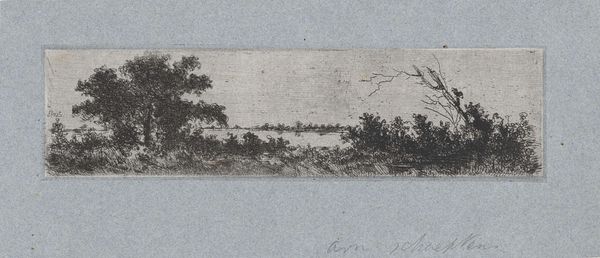

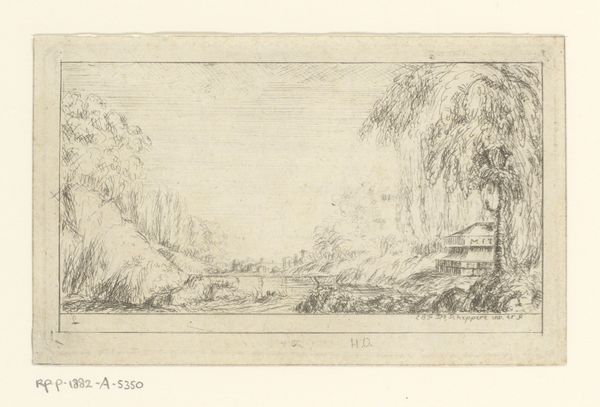

Dimensions: height 21 mm, width 93 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Antoine de Marcenay de Ghuy’s “River Landscape with a Figure on Crutches” from 1773, an etching depicting…well, a river landscape. Editor: My initial thought is one of melancholy, a kind of serene sorrow hangs over it, likely fueled by the image of that lone figure, seemingly injured, hobbling through the wilderness. Curator: Yes, melancholy was very in vogue then. De Ghuy was working in the twilight of the Rococo period, right on the cusp of the Romantic movement. The figure invites the viewer to reflect on the sublime power of nature but also perhaps the fleeting nature of human existence. Editor: An etching, of course, being all about labor intensive lines etched onto metal. Thinking about its production makes me appreciate the tonal variation achieved, this really wouldn’t have been mass-produced. Do you see it as more of a commodity or art piece for its time? Curator: Both, absolutely. Printmaking served the elite with personalized landscapes, allowed wider circles of the population to engage with these works. So art, commodity, also a political act of democratizing imagery. Editor: I think there is more to the landscape though. Considering the limitations of the technique and that he didn't have cameras or ready transportation... De Ghuy captured more than just nature, his material craft translated emotion, he wasn’t merely reproducing something he had seen! Curator: Exactly. He presents nature filtered through a subjective, idealized lens—a Romantic characteristic that positioned the artist as a sensitive, emotional being. The use of the figure serves a similar purpose. De Ghuy offers more than a vista. He proposes a meditation. Editor: This has altered my perspective of how the print functioned. Considering how this single sheet made its journey to become something preserved and cherished centuries later. What a statement on how artwork materializes culture. Curator: I'm now even more fascinated with its status as a vehicle for social discourse and identity at the end of the 18th century. Editor: It makes one think about value, labor, emotion and context and their material impact, quite amazing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.